Ten Years and Counting: My Affair with Microservices

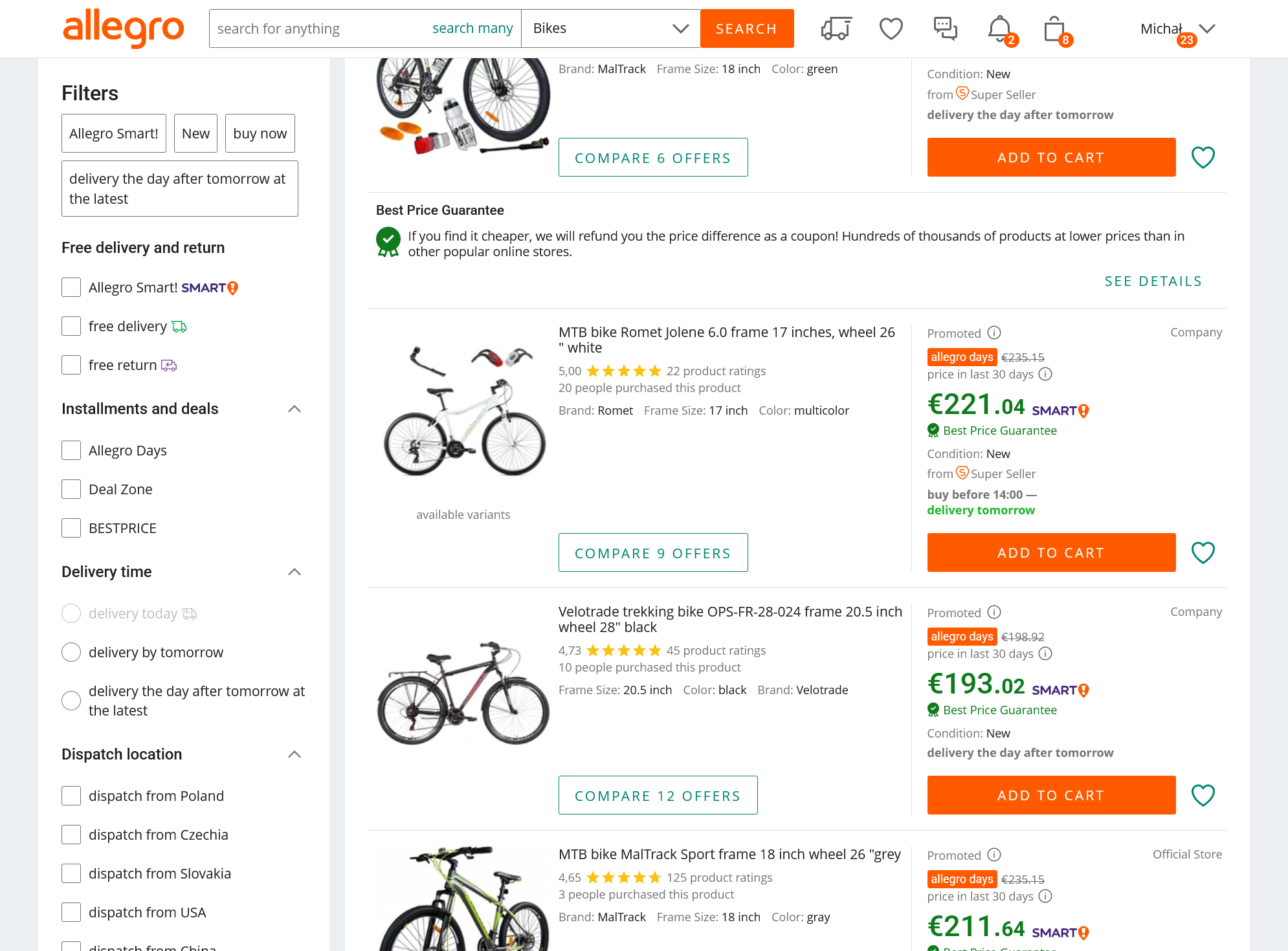

In early 2024, I hit ten years at Allegro, which also happens to be how long I’ve been working with microservices. This timespan also roughly corresponds to how long the company as a whole has been using them, so I think it’s a good time to outline the story of project Rubicon: a very ambitious gamble which completely changed how we work and what our software is like. The idea probably seemed rather extreme at the time, yet I am certain that without this change, Allegro would not be where it is today, or perhaps would not be there at all.

Background #

Allegro is one of the largest e-commerce sites in Central Europe, with 20 million users and over 300 million offers. It was founded in 1999, originally with just the Polish market in mind. The story I want to tell you starts in 2013, a year before I joined.

In 2013, the site was already large and relevant, but its commercial success and further growth led to development bottlenecks emerging. The codebase was a monolithic PHP application, with some auxiliary processes written in C. Checked out, the git monorepo weighed about 2 GB, and the number of pull requests produced daily by a few hundred developers was so large that if you started a new branch in the morning, you were almost sure to get some conflicts if you wanted to merge in the afternoon. The system was centered around a single, huge database, with all the performance and architectural challenges you can imagine. Tests were brittle and took ages to finish. Deployment was a mostly manual and thus time-consuming processes that required lots of attention and ran the risk of causing a serious problem in production if something went wrong. It was so demanding and stressful I still remember my team having to run the deployment once (in place of the usual deployers) as a big event.

Rubicon Rises #

![]() It was becoming clear that we would hit a wall if we continued working this way. So, around 2012/2013, the idea for a complete overhaul of the architecture

started to emerge. We began experimenting with SOA (Service-Oriented Architecture) by

creating a small side project, the so-called New Platform, in PHP, as a proof-of-concept. We also decided we would start doing

Agile, TDD, and

Cloud. After a short while, on top of this, we decided to switch to Java for backend development.

It was becoming clear that it would be a revolution indeed, requiring everyone to change

the way they worked, and to switch out the whole development ecosystem, starting with the core programming language. Once we got this going, there would be

no turning back, so a matching name also appeared: Project Rubicon.

It was becoming clear that we would hit a wall if we continued working this way. So, around 2012/2013, the idea for a complete overhaul of the architecture

started to emerge. We began experimenting with SOA (Service-Oriented Architecture) by

creating a small side project, the so-called New Platform, in PHP, as a proof-of-concept. We also decided we would start doing

Agile, TDD, and

Cloud. After a short while, on top of this, we decided to switch to Java for backend development.

It was becoming clear that it would be a revolution indeed, requiring everyone to change

the way they worked, and to switch out the whole development ecosystem, starting with the core programming language. Once we got this going, there would be

no turning back, so a matching name also appeared: Project Rubicon.

The project had such a broad scope that it even came with its own constitution, a set of high-level guidelines to be used in case of doubt. It focused mostly on ways of working and highlighted the value of learning (on personal, team, and company level), testing, reuse, empirical approach to software development, and active participation in the open-source community both as users and as contributors. Specific technical assumptions included:

- focus on quality

- microservices

- distributed, multi-regional, active-active architecture

- Java

- cloud deployment

- using open-source technologies

There was also a list of success criteria for the project:

- the monolith is gone

- we have Java gurus on board

- we have services

- development is faster

- we have continuous delivery

- we don’t have another monolith

- we still make money

Faster development was probably the most important goal, since slow delivery was the direct reason we embarked on this long journey.

On top of these lists, more detailed plans were made as well, of course. For example, various parts of the system were prioritized for moving out of the monolith as we were well aware we would not be able to work on everything at once. Being Agile does not mean planning is to be avoided, only that plans have to be flexible. So, armed with a plan, we got off to work.

Execution #

Too much has happened during the 10+ years to report here. The initial period was really frantic since we had to set up everything, and, first of all, teams had

to switch to a new mindset. This was also a period of intense hiring, and the time I joined the recently opened office in Warsaw. Microservices were at that

time only starting to gain traction, so while we used the experiences of others as much has possible, we had to learn many things ourselves, sometimes learning

them the hard way.

Too much has happened during the 10+ years to report here. The initial period was really frantic since we had to set up everything, and, first of all, teams had

to switch to a new mindset. This was also a period of intense hiring, and the time I joined the recently opened office in Warsaw. Microservices were at that

time only starting to gain traction, so while we used the experiences of others as much has possible, we had to learn many things ourselves, sometimes learning

them the hard way.

To give you an idea of the pace, here are just some of the things that happened in 2013:

- outline of the common architecture (service discovery, logging) created

- a set of common libraries created (presentation from 2016)

- training in Java and JVM for PHP developers

- recruitment of Java developers started

- first Java code got written

- fierce discussions about technology choices (Guice vs Spring, Maven vs Gradle, Jetty vs Undertow)

What followed in 2014 (this is the part I could already experience in person):

- various self-service tools allowing developers to handle common tasks such as creating databases themselves rather than by involving specialized support teams

- automation tools

- development of Hermes, our open-source message broker built on top of Kafka, started

- strategic DDD training with Eric Evans

- migration to Java 8

- global architecture improvements

- allegro.tech, the project to coordinate the visibility of our tech division online and offline, of which this blog is a part, started

- SRE team created

- CQK (Code Quality Keepers) guild opened

- first Java services deployed to production

- intense recruitment and learning

The number of both production services and of tools supporting developers’ work that got created thereafter is staggering. It should be clear from just the list above that this was a huge investment, and could only proceed due to full buy-in of both technology and business parts of the company. It was indeed a gamble, well-informed, but still a gamble that carried big risk should it fail, but an even greater risk if we were to stay with the old architecture.

At this point you probably can see that actually building microservices seems like a minor part of the whole undertaking. There was a lot of work to writing so many parts of this huge system anew, but indeed the amount of work that we had to invest into infrastructure, tooling, and learning, was immense. It was also absolutely critical for the project’s success. A lot has been said about microservices, and it is true that for them to be beneficial, you need the right scale and the right kind of system. We had both, and so the decision to move to microservices proved to be worthwhile, but despite knowing the theory, I think no one expected the amount of auxiliary work to be so huge. Indeed, while microservices themselves may be simple, the glue that holds them together is not.

Flashbacks #

Summarizing ten years of rapid development is tough, so instead of trying to tell you the full story, I decided to share a few flashbacks: moments which I remembered for one reason or another.

No-ing SQL #

When refactoring our huge monolith into smaller microservices, we needed to also choose the

database to use for each of them. Since horizontal scalability was our focus, we preferred NoSQL databases when possible.

This was a big change since the monolithic solution relied on a single, huge SQL database. On top of that, it was not modularized well, and in many places

there was little or no separation between domain and persistence layers. If the monolith was structured well, splitting it into separate services would have

been much easier. Unfortunately, this was not the case, so we had to perform the transition to NoSQL together with other refactorings and cleanup. Usually,

we had to deeply remodel data and operations handling it, especially transactional, so that they could be executed in the new environment. This was often

a significant effort even if we could divide the code in such way that the transaction or set of related operations ended up within the same service. Things

became even more complicated if an operation spanned multiple services (and databases) in the new architecture. This is one of the reasons why dividing a

big application into smaller chunks is much harder than it may seem at first.

When refactoring our huge monolith into smaller microservices, we needed to also choose the

database to use for each of them. Since horizontal scalability was our focus, we preferred NoSQL databases when possible.

This was a big change since the monolithic solution relied on a single, huge SQL database. On top of that, it was not modularized well, and in many places

there was little or no separation between domain and persistence layers. If the monolith was structured well, splitting it into separate services would have

been much easier. Unfortunately, this was not the case, so we had to perform the transition to NoSQL together with other refactorings and cleanup. Usually,

we had to deeply remodel data and operations handling it, especially transactional, so that they could be executed in the new environment. This was often

a significant effort even if we could divide the code in such way that the transaction or set of related operations ended up within the same service. Things

became even more complicated if an operation spanned multiple services (and databases) in the new architecture. This is one of the reasons why dividing a

big application into smaller chunks is much harder than it may seem at first.

Cassandra was initially our preferred NoSQL database for most tasks. Only after a while did we learn that each database is good for some use cases and bad for others, and that we needed polyglot persistence to achieve high performance and get the required flexibility in all cases. The team I worked on was among the first Cassandra adopters at the company, and as is often the case when you run something in production for the first time, we uncovered a number of issues in our Cassandra deployment which was “ready” but not tested in production yet. The team responsible for the DB was learning completely new stuff just as we were.

An argument sometimes put up against the need to separate your application’s persistence layer from the domain logic is “you’re never going to switch out the DB for another one anyway”. Most of the time that’s true, but in one service we did have to switch from Cassandra to MongoDB after we found out our access patterns were not very well aligned with Cassandra’s data model. We managed to do it inside a single two-week sprint, and apart from the service becoming faster, its clients would not notice any difference as the external API stayed the same. While the (usually theoretical) prospect of switching databases is not the only reason for decoupling domain and persistence layers, it did help a lot in this case, and it is about this time I started to understand why we were creating so many classes even though you could just cram all that code into one.

I also managed to kill our Cassandra instance once when I was learning about big data processing and created a job that was supposed to process some data from the DB. The job was so massively parallel that the barrage of requests it generated overwhelmed even Cassandra. Fortunately, this situation also showed the advantage of having separate databases for each service, as only that single service experienced an outage.

Into the cloud #

Before joining Allegro, I had only deployed to physical servers, so moving to the cloud was a big change. At first, we deployed our services to virtual

machines configured in OpenStack. What a convenience it was to be able to just set up a complete virtual server with a few

clicks rather than wait days for a physical machine. We used Puppet to fully configure the virtual machines for each service, so

while you had to write some configuration once, you could spin up a new server configured for your service almost instantly afterwards.

Before joining Allegro, I had only deployed to physical servers, so moving to the cloud was a big change. At first, we deployed our services to virtual

machines configured in OpenStack. What a convenience it was to be able to just set up a complete virtual server with a few

clicks rather than wait days for a physical machine. We used Puppet to fully configure the virtual machines for each service, so

while you had to write some configuration once, you could spin up a new server configured for your service almost instantly afterwards.

This IaaS (Infrastructure as a Service) approach was very convenient, and quite a change, but in

many ways it still resembled what I had known before: you had a machine, even if virtual, and you could ssh and run any commands there if you wanted, even

if it was rarely needed since Puppet set up everything for you.

The real revolution came when we switched to PaaS (Platform as a Service) model, at that time based on

Mesos and Marathon. Suddenly, there were no more virtual machines, and you could not ssh

to the server where your software was running. For me, this was a real culture shock, and even though up to this point I was very enthusiastic about all the

cool technology we were introducing, the thought of no more ssh freaked me out. How would I know what was going on in the system if I couldn’t even access

it? Despite my reservations, I gradually found out you could indeed deploy and monitor software despite not being able to access the machine via ssh. It

sounds weird in retrospect, but this was one of the most difficult technological transitions in my career.

After a while, we built some abstraction layers on top of Mesos, including a custom app console that allows you to deploy a service and perform all maintenance tasks. It isolates you from most details of the underlying system, and is so effective that when we migrated from Mesos to Kubernetes later on, the impact on most teams was much smaller that you could imagine for such a big change. Our App Console is an internal project, but if you are familiar with Backstage, it should give you an idea of what kind of tool we’re talking about here.

Monitoring #

Believe it or not, initially all monitoring was centralized and handled by a single team. If you wanted to have any non-standard charts in

Zabbix or any custom alerts (and obviously, you wanted to), you had to create a ticket in JIRA, describe exactly what you wanted,

and after a while, the monitoring team would set it up for you. The whole process took about a week, and quite often, right after seeing the new chart you

knew you wanted to improve it, so you would file another ticket and wait another week. Needless to say, this was incredibly frustrating, and I consider it

one of my early big successes when I kept pushing the monitoring team until they finally gave in and allowed development teams to configure all of their

observability settings themselves.

Believe it or not, initially all monitoring was centralized and handled by a single team. If you wanted to have any non-standard charts in

Zabbix or any custom alerts (and obviously, you wanted to), you had to create a ticket in JIRA, describe exactly what you wanted,

and after a while, the monitoring team would set it up for you. The whole process took about a week, and quite often, right after seeing the new chart you

knew you wanted to improve it, so you would file another ticket and wait another week. Needless to say, this was incredibly frustrating, and I consider it

one of my early big successes when I kept pushing the monitoring team until they finally gave in and allowed development teams to configure all of their

observability settings themselves.

Going polyglot #

While Rubicon started out with the premise of rewriting our software in Java, we quickly started experimenting with other JVM languages. The team I worked

on considered Scala for a while, but after some experimentation decided against using it as our main language. Some other teams, however, did choose it, and

even though they are a minority at Allegro, we have some microservices written in Scala to this day. On the other hand, Scala is the dominant language at

Allegro when it comes to writing Spark jobs.

While Rubicon started out with the premise of rewriting our software in Java, we quickly started experimenting with other JVM languages. The team I worked

on considered Scala for a while, but after some experimentation decided against using it as our main language. Some other teams, however, did choose it, and

even though they are a minority at Allegro, we have some microservices written in Scala to this day. On the other hand, Scala is the dominant language at

Allegro when it comes to writing Spark jobs.

Some time around 2015, a teammate found out there was a relatively new, but promising, language called Kotlin. It so happened that we were just starting work on a new microservice which was still very simple and not quite critical. He decided to use it as a testbed, and within I think two days rewrote the whole thing in Kotlin. Thanks to the services being independent and this one not being very important yet, we could safely experiment in production and assess the stability of the rewritten service. Learning the language by writing actual production-ready code rather than just playing with throw-away code allowed us to check what advantages and disadvantages the language offered under realistic usage scenarios. Kotlin caught on, and gradually we started to use it for more and more new services and to use it for new features in existing Java services as mixing the two was easy. Many services already used Groovy and Spock for tests anyway. At this point, Kotlin is more popular than Java at Allegro, and on our blog we published some articles about Kotlin, including one which unfortunately stirred a lot of controversy, and caused a (deserved IMO) shitstorm both inside and outside the company.

Besides JVM languages, we by now have also microservices written in C#, Go, Python, Elixir, and probably a few more languages I forgot to mention. This is just the backend, but our frontend architecture also allows for components written in various languages. And besides customer-facing business code, there are also internal tools and utilities, sometimes written using yet other general-purpose languages and DSLs. Finally, there’s the whole world of AI, including prompting for generative AI that you can also consider a programming language of sorts.

The main point I want to make here is that using microservices has allowed us to safely experiment with various programming languages, to consciously limit the blast radius of those experiments should anything go wrong, and to perform all transitions gradually. Of course, this all has a purpose: finding the best tool for the job, and using all the different languages’ strengths where they can help us most. It is not about introducing new tools just for the sake of it, which would cause but chaos and introduce risks related to future maintenance. I think the autonomy teams get in making technical decisions, yet combined with responsibility for the outcomes, is what allows us to learn and find new ways of doing things while at the same time it limits the risks associated with experimenting. As in many other cases, things work well when the organization’s ways of working (team autonomy) are aligned with technical solutions (microservices).

Using antipatterns wisely #

Good practices are heuristics: most of the time, following them is a good idea. For example,

two microservices should not share database tables since this introduces tight coupling: you can’t introduce a change to the schema and deploy just one service

but not the other. Your two services are not independent, but form a distributed monolith instead. Avoiding such situations is just common sense.

Good practices are heuristics: most of the time, following them is a good idea. For example,

two microservices should not share database tables since this introduces tight coupling: you can’t introduce a change to the schema and deploy just one service

but not the other. Your two services are not independent, but form a distributed monolith instead. Avoiding such situations is just common sense.

Still, you should always keep in mind the reasons why a good practice exists, what it protects you from and what costs it introduces. At one point we had a discussion within our team about how to best handle a peculiar performance issue. Our service connected to an Elasticsearch instance and performed two kinds of operations: reads and writes. Reads were much more numerous, but writes introduced heavy load (on the service itself — Elastic could handle it). Writes came in bursts, so most of the time things worked well, but when a burst of writes arrived, performance of the whole service suffered and read times were affected. We tried various mechanisms for isolating the two kinds of operation, but couldn’t do it effectively.

A colleague suggested we split the service in two, one responsible for handling reads and the other for writes. We had a long discussion, in which I presented arguments for having a single service as the owner of the data, responsible for both reads and writes, and highlighted what issues could arise due to the split. While keeping the service intact seemed to be the elegant thing to do, I didn’t have a good solution for the performance issue. My colleague’s idea to split the service, on the other hand, while somewhat messy, did offer a chance to solve it.

So, we decided to just try it and see whether this approach would solve the performance issue and how bad the side effects would be. We did just that, and the antipattern-based solution worked great: performance hiccups went away, and despite sharing the common Elasticsearch cluster, the two services remained maintainable. We were not able to fully assess this aspect right away, but time proved my colleague right as well: during the 3+ years we worked with that codebase later on, we only ran into issues related to sharing Elasticsearch once, and we managed to fix that case quickly. It certainly did help, though, that both services kept being developed by the same team, and that by the time we introduced the split, the schema was already quite stable and did not change often. Nonetheless, had I insisted on keeping things clean, we would have probably spent much more time fighting performance issues than we lost during the single issue that resulted from sharing Elasticsearch between services. Know when to use patterns, know when to use antipatterns, and use both wisely.

One size does not fit all #

I think we’ve always been quite pragmatic about sizing our microservices. It’s hard to define a set of specific rules for finding the right size, but going

too far in one direction or the other causes considerable pain. Make a service huge, and it becomes too hard for a single team to maintain and develop, or

scaling issues arise similar to those you could experience with a monolith. Make it very small, and you might get overwhelmed by the overhead of having your

logic split between too many places, issues with debugging, and the performance penalty of the system being distributed to the extreme.

I think we’ve always been quite pragmatic about sizing our microservices. It’s hard to define a set of specific rules for finding the right size, but going

too far in one direction or the other causes considerable pain. Make a service huge, and it becomes too hard for a single team to maintain and develop, or

scaling issues arise similar to those you could experience with a monolith. Make it very small, and you might get overwhelmed by the overhead of having your

logic split between too many places, issues with debugging, and the performance penalty of the system being distributed to the extreme.

Most services I got to work on at Allegro were not too tiny, and contained some non-trivial amount of logic. There were sometimes agitated discussions about where to implement a certain feature, in particular whether it should be in an existing service or in a new one. In hindsight, I think most decisions made sense, but there were certainly cases where a feature that we believed would grow ended up in a new service which then never took off and remained too small, and cases where something was bolted onto an existing service because it was easier to implement this way, but which caused some pain later on.

I think I only once saw a team fall into the nanoservice trap where services were designed so small the split caused more trouble than it was worth. On the other hand, there were certainly services which you could no longer call micro by any stretch. This was not necessarily a bad thing. As long as a service fulfilled a well-defined role, a single team was enough to take care of it, and it was OK that you had to deploy and scale the whole thing together, things were fine. In some cases of services which grew really much too big (indicators being that they contained pieces of logic only very loosely related to each other, and that at some point multiple teams were regularly interested in contributing), we did get back to them and split them up. It was not very easy, but doable, and the second-hardest part was usually finding the right lines along which to divide. The only thing harder was finding the time to perform such operations, but with a bit of negotiation and persistence, after a while we usually succeeded.

There is an ongoing discussion of whether we have too many microservices. It’s not an urgent thing, but there are reasons to not go too high, such as certain technical limitations in the infrastructure and the cost of overprovisioning (each service allocates resources such as memory or CPUs with a margin, and those margins add up). Still, the fact that we are well above a thousand services and yet their number is only a minor nuisance, speaks well of our tooling and organization. Indeed, thanks to some custom tools, creating a new service is very easy (maybe too easy?), and managing those already there is also quite pleasant. This is possible due to huge investments we made early on (and continue): we knew right from the start that while each microservice may be relatively simple, a lot of complexity goes into the glue that holds the whole system together. Without it, things would not quite work so well. Another factor is, obviously, that our system has an actual use case for microservices: we have hundreds of teams, a system that keeps growing in capacity and complexity, and scale that makes a truly distributed system necessary. I think much of the anti-microservice sentiment you see around the internet today stems from treating microservices as a silver bullet that you can apply to any problem regardless of whether they actually make sense in given situation, or from not being aware that they can bring huge payoffs but also require great investments. There is a good summary of the advantages and disadvantages of microservices in this Gitlab blog post.

Service Mesh and common libraries #

Probably the most recent really significant change related to our microservice ecosystem was the migration to service mesh.

From developers’ perspective it did not seem all that radical, but it required a lot of work from infrastructure teams. The most important gain is the

possibility to control some aspects of services’ behavior in a single place. For example, originally if you wanted to have secure connections between

services, you had to support TLS in code, using common libraries. With service mesh, you can just

enable it globally without the developers even having to know. This makes maintaining the huge ecosystem that consists of more than a thousand services much

more bearable.

Probably the most recent really significant change related to our microservice ecosystem was the migration to service mesh.

From developers’ perspective it did not seem all that radical, but it required a lot of work from infrastructure teams. The most important gain is the

possibility to control some aspects of services’ behavior in a single place. For example, originally if you wanted to have secure connections between

services, you had to support TLS in code, using common libraries. With service mesh, you can just

enable it globally without the developers even having to know. This makes maintaining the huge ecosystem that consists of more than a thousand services much

more bearable.

Each microservice needs certain behaviors in order to work well within our environment. For example, it needs a healthcheck endpoint which allows Kubernetes to tell if the service instance is working or not. We have a written Microservice Contract which defines those requirements. There are also features that are not strictly necessary, but which many services will find useful, for example various metrics. Our initial approach was to have a set of common libraries that provided both the required and many of the nice-to-have features. Of course, if you can’t or don’t want to use those libraries, you are free to do so, as long as your service implements the Microservice Contract some other way.

Over time, the role of those libraries has changed, with the general direction being that of reducing their scope. There are several reasons.

Reason number one is more and more features can be moved to infrastructure layer, of which Service Mesh is an important part. For example, originally communicating with another service required a service discovery client, implemented in a shared library. Now, all this logic has been delegated to the Service Mesh and requires no special support in shared libraries or service code.

Another reason is that open source libraries have caught on and some features we used to need to implement ourselves, such as certain metrics, are now available out of the box in Spring Boot or other frameworks. There is no point in reinventing the wheel and having more code to maintain.

Finally, the problem with libraries is that updating a library in 1000+ services is a slow and costly process. Meanwhile, a feature that the Service Mesh provides can be switched on or reconfigured for all services almost instantly.

Despite common libraries falling out of favor with us, there are some features that are hard to implement in infrastructure alone. Even with a simple

feature such as logging, sometimes we need data that only code running within the services has access to. When we want to fill in certain standard fields in

order to make searching logs easier, some fields, such as host or dc, can easily be filled in by the infrastructure, but some, such as thread_name are

only known inside the service and can’t be handled externally. Thus, the role of libraries is diminished but not completely eliminated. In order to make

working with shared libraries less cumbersome, we are working on ways to automate upgrades as much as possible so that we can keep all versions up to date

without it costing too much developers’ time.

Learning #

During the transition, Allegro invested in learning and development heavily. Daily work was full of learning opportunities since everything we were doing

was quite new, and many approaches and technologies were not mature yet. We were really on the cutting edge of technology, so for many problems there were

simply no run-of-the-mill solutions yet. We were already several years into the microservice transition when microservices became a global hype.

During the transition, Allegro invested in learning and development heavily. Daily work was full of learning opportunities since everything we were doing

was quite new, and many approaches and technologies were not mature yet. We were really on the cutting edge of technology, so for many problems there were

simply no run-of-the-mill solutions yet. We were already several years into the microservice transition when microservices became a global hype.

Since everybody was well aware of what an ambitious plan we were pursuing, it was also well understood that some things took experimenting, and while of course we were expected to ship value, there was a company-wide understanding that time for learning, team tourism, trying out new things, and sometimes failing, were necessary for success. One of the things I really enjoyed was the focus on quality and doing things right. Business understood this as well, and actually at one point when Rubicon was quite advanced, developers were granted a 6-month grace period during which we could focus on just technical changes without having to deliver any business value. As a matter of fact, many business logic changes were delivered anyway. For example, the team I was on created a microservice-based approach to handling payments which was much more flexible than the old solution, so it was not just a refactoring, but rather a rewrite that took new business requirements into account.

Apart from learning by doing, we also invested in organized training and conferences. We bought a number of dedicated training sessions with established experts from Silicon Valley on topics such as software architecture and JVM performance. Pretty much everyone could attend at least one good conference each year, and we also sponsored a number of developer-centric events in order to gain visibility and attract good hires. About a year into my job, I got to attend JavaOne in San Francisco, whose scale and depth trumped even the biggest conferences I knew from Europe. After attending a few conferences, I decided to give speaking myself a try, and was able to take advantage of a number of useful trainings to help me with that. We also started the allegro.tech initiative in order to organize all the activity used to promote our brand, and this blog is one of the projects that we run under the allegro.tech umbrella to this day.

The cycle of life #

In 2022, a service I had worked on when I first started at Allegro was shut down due to being replaced with a newer solution. This way, I witnessed the full lifecycle of a service: building it from scratch, adding more features to the mature solution, maintenance, and finally seeing it discontinued. It was really a great experience to see that something I had built had run its course and I could be there to see the whole cycle.

Takeaways #

When we started out working with microservices, we were well aware of their benefits but also of their cost. The famous

You must be this tall to use microservices image adorned many of our presentations at that

time. By taking a realistic stance, we avoided many pitfalls. Our transition to the microservice world took several years, but was successful, and I am

certain we would be in a much worse place had the company not made that bold decision. Apart from being a huge technical challenge, it was also a great

transformation in our way of thinking and in the way we work together. Conway’s Law applies and the change

in system architecture was possible only together with a change in company architecture. It was also possible thanks to many smart people with whom I had

the pleasure to work over these years.

When we started out working with microservices, we were well aware of their benefits but also of their cost. The famous

You must be this tall to use microservices image adorned many of our presentations at that

time. By taking a realistic stance, we avoided many pitfalls. Our transition to the microservice world took several years, but was successful, and I am

certain we would be in a much worse place had the company not made that bold decision. Apart from being a huge technical challenge, it was also a great

transformation in our way of thinking and in the way we work together. Conway’s Law applies and the change

in system architecture was possible only together with a change in company architecture. It was also possible thanks to many smart people with whom I had

the pleasure to work over these years.

When I look back, I see how far we have come. Creating a new service used to take a week or two at first, and now it takes minutes. Scaling a service required a human operator, creating virtual machines, and manually adding them to the monitoring system. Today, an autoscaler handles most services and developers do not even need to know that instances were added or removed. Our tooling is really convenient, even though there are things we could improve, and some components are already showing signs of aging. Nonetheless, many things that used to be a challenge, are trivial today. New joiners at the company can benefit from all these conveniences right from the start, and sometimes I think they might not fully appreciate them since they never had to perform all that work manually.

The world does not stand still, though. Technologies change, and some assumptions we made when planning our architecture ten years ago, have already had to be updated. Our system has grown, and so has the company, so many issues we are dealing with now are different from those that troubled us in the beginning of Project Rubicon. Initially, everything was a greenfield project, but by now, some places have accumulated bit rot and need cleanup. The system is much bigger (which microservices enabled) so introducing changes gets harder (still, much easier than it would be within a monolith). And since ten years is a lot of time, many people have moved through the company, so knowledge transfer and continued learning are still essential. Only change is certain, and this has not changed a bit. I’m happy I could experience the heroic age of microservices myself, and I’m looking forward to whatever comes next.