How to migrate to Java 8

This post is about migrating a real-world, non-trivial, business-critical application from Java 7 to Java 8. When searching for a JDK 8 migration guide, you can often find blog posts that claim to be helpful but in reality only repeat the list of features found in release notes and offer no insight into issues you may encounter in practice. Having no migration guide during our own migration, we decided to create one. This is a report right from the trenches, no details spared, casualties included.

Why Java 8? #

Java 7 never failed us so far and we have always been able to achieve what we wanted. Migration to Java 8 was certainly not a necessity. However, we are always looking for tools facilitating our work, helping us write code better and faster. This makes new language features worth evaluating. Besides, we expect that various libraries and tools will soon start taking advantage of Java 8, so after some time using Java 8 will become more of a necessity. It is better to be ahead of the crowd and to migrate now than to wait until we are forced to. We also expected gains in productivity from new features such as lambda expressions, so reaping these benefits reasonably early seemed like a good idea.

You may wonder why we wanted to spend time on Java 8 with Scala being around. At Allegro, development teams have a lot of freedom in choosing the technology stack they want to use, as long as they take full responsibility for the products they develop. This allows for testing out new ideas without putting the delivery of business value at risk. We do write some code in Scala (some teams even use Scala as their major language), there are guys using some Clojure here and there, and there are dozens of technologies which get some use in a team or two. Fortunately, since the whole ecosystem is based on JVM, lots of interoperability is possible between code written in different JVM-based languages.

However, there is a default stack, and it is based on Java. Java still makes up the majority of code written at the company. This means that Java is and will be around for quite some time. With Java code aplenty, migrating to Java 8 (which is almost completely backwards-compatible with Java 7) was a reasonable choice. It allowed us to take advantage of new features (such as elements of functional programming) without the need to completely modify the way we create software.

As you will see, an ecosystem of tools and infrastructure is an important part of the software development process. Despite much progress on Scala’s side, the toolset for Java seems to still be more mature, and is more widely known and used by developers. This must be taken into account and may be a reason for sticking with Java, or for using it alongside other JVM languages.

Best way to migrate: write new code in a new way #

Applications we develop are microservices. The pros and cons of microservice-based architectures have been discussed countless times, but one thing has not been stressed enough: with microservices you often get the chance to start a new project.

This is a very good thing. It allows you to try out new technologies on small projects, which is much easier and safer than migrating existing large applications. So a quick answer to “how we migrated to Java 8” could have been: we didn’t. We simply started writing new code in Java 8, and it went almost seamlessly.

Reasons for migrating #

But then, what is this article about? In order to fully take advantage of Java 8, we wanted to understand well both new features and potential pitfalls. The best way of learning this sort of things is learning by doing. With both new and older projects in mind, we wanted to acquire this knowledge fast in order to take advantage of it as soon as possible. We thought that migrating an existing, non-trivial application would pay off. The application we selected is still maintained and developed, so any gains in code readability and maintainability would have a practical impact.

Before we started #

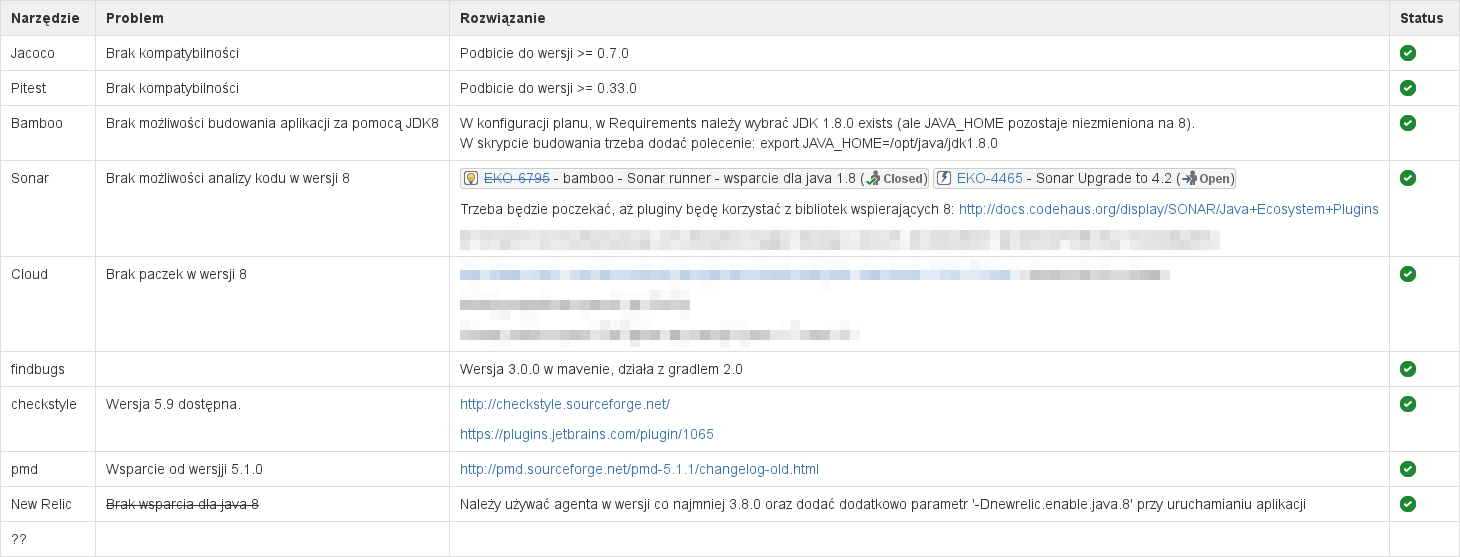

Even before an official release of JDK 1.8.0, people were looking at pre-release builds in order to check if their applications would compile and run. But serious software development takes much more than that. Creating high-quality software goes far beyond writing code. There are a lot of tools which facilitate this task: static code and bytecode analysis tools such as FindBugs, PMD and CheckStyle, Continuous Integration (Bamboo in our case), systems for deploying services in the cloud and system images. They all needed support for JDK 8.

We had to make sure all these systems would be ready for Java 8 before we could move production software to the new JDK version. A checklist was created in our internal Wiki which listed known missing elements of the puzzle, and it was updated as we learned about solutions to existing problems, for example new releases of libraries which added JDK 8 support. Thanks to being able to receive notifications about page updates via e-mail, everyone interested could stay up-to-date on our readiness status. With a shared status page, different teams didn’t have to waste time by solving the same issues over and over again, and preparing for the migration became a company-wide effort. Our Solutions Architects were central to making this happen and were able to solve a lot of issues. I talked to one of these guys at a time when FindBugs was not yet compatible with Java 8. He had already understood the cause and even had a patch, he just didn’t want to deploy it company-wide until it was merged upstream.

The test subject #

The application we chose as our test subject was a RESTful service called Flexible Pricing which is used for calculating the fees users pay when they list items for sale and the commissions they pay when their items get bought. As you can imagine, this system is pretty critical to our e-commerce site allegro.pl as well as to our sites in other countries. The technology stack included Java, Spring, Cassandra and MongoDB as NoSQL data storage, some AOP code, Jersey and a ton of minor technologies for performing specific tasks.

There are also a lot of unit and integration tests and test coverage is pleasantly high, which soon proved to be crucial for a successful migration to Java 8.

Java 8: first blood #

Once we decided to commit some time to verifying what kind of benefits migrating to JDK 8 would bring to us, the first thing to try was just installing the new JDK and checking if our application would compile and run.

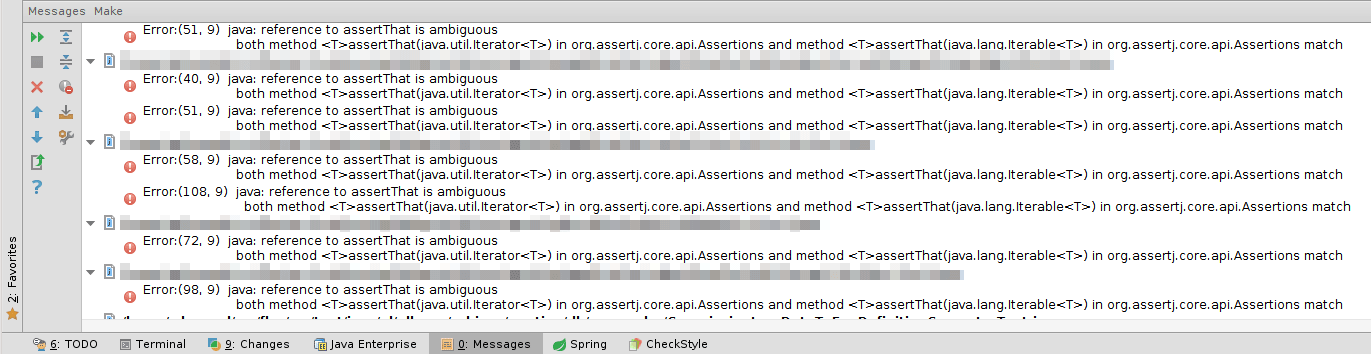

It wouldn’t even compile.

This was a surprise. After all, Java tends to be backwards-compatible with previous releases, sometimes even at the cost of preserving some really old and weird features. Fortunately, errors were limited to test code. We soon found out that they were caused by a change introduced to the type inference mechanism and were triggered by using assertj together with catch-exception. Apparently, this is actually a feature, actually even a bug-fix, and according to Oracle original code which worked in Java 7 should not have worked in the first place.

Without delving much into the details of the change, we were able to work around it by explicitly casting the result of

caughtException() to Exception (the method’s signature says public static

Deploying the app with Java 8 #

After getting the app to compile and run, making sure that all tests passed and some manual testing, we wanted to deploy it without any further changes. It is a good idea to always test, as far as possible, only a single change at a time. It makes detecting and fixing issues much easier. Just imagine running an application with multiple changes only to find out that nothing works and trying to locate the cause. Therefore, we wanted to deploy the service on Java 8 and to monitor it for some time before we started refactoring code in order to take advantage of Java Eight’s new features.

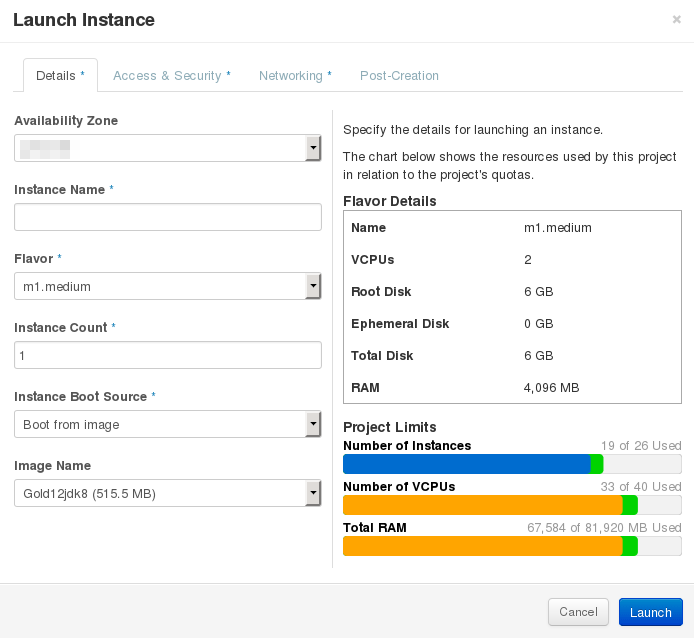

Fortunately, our migration checklist in the Wiki contained an item related to preparing the cloud environment where our apps are deployed. Infrastructure team had already prepared system images with Java 8 on board, so we just had to modify our Puppet script and rebuild the machines. Of course, we first did this in a test environment. Next, we deployed the app to a single production machine. Only after it had performed without errors for a day or two we put the Java 8 version of our app on all production machines. It did, of course, help us a lot that we had some pretty advanced monitoring in place which gave us confidence that the system was working properly.

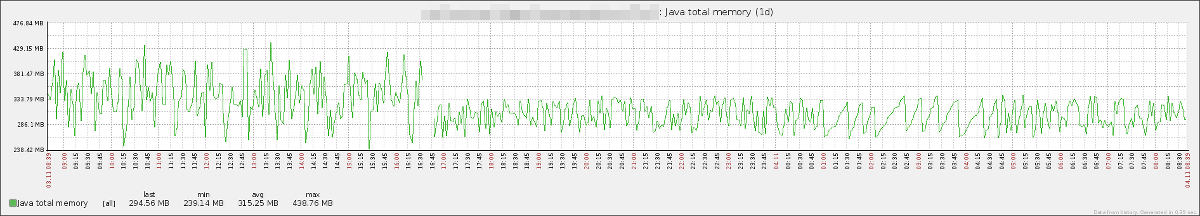

Once we were sure everything worked well, it was time for some cleanup. We use Gradle as our build tool, and our build.gradle script included some extra JVM flags, such as -XX:PermSize for setting the size of permanent generation in the Garbage Collector. Since permgen space was removed in JDK 8, this flag was causing warnings, so we removed it. We also decided to give the G1 (Garbage-First) Garbage Collector a try. It had been available in previous JDK versions for quite some time so with JDK 8 release it should have been ready for prime time. After changing the Concurrent Mark Sweep (CMS) Garbage Collector to G1, we did not notice any change in performance or stability. However, we did notice that the initial working set size of the application dropped by about 10% whereas the amplitude of its changes decreased, suggesting more frequent, and smaller collections.

At the same time, we noticed a little premature tenuring which was absent before. However, it did not affect GC pauses in any considerable way. After about a day, G1 increased the heap size and premature tenuring went away, with heap size remaining stable afterwards. CMS is known to be very unlikely to automatically resize the heap, so I would say that G1 did a better job at automatically tuning its parameters than CMS. Other things being equal, we stayed with G1.

Java 8 may have introduced changes to the way objects are represented internally, which could influence memory consumption and GC behavior. We knew, for example, that the implementation of HashMap had been changed in JDK 8 but we didn’t analyze it in more detail.

Using Java 8 features #

Now that we had successfully deployed Flexible Pricing on JDK 8, we wanted to benefit from all new features of Java 8. We were also eager to compare certain features to their Scala counterparts.

There are a lot of changes listed in the JDK 8 release notes but the two we had highest hopes for were elements of functional programming and the new date-time API. There were also improvements which looked nice but for which we found no direct uses in this particular project, such as repeating annotations, extensions to java.util.concurrent and cryptography or unsigned arithmetic. However, we did benefit indirectly from default methods in interfaces since Oracle used them to extend the collections API without breaking compatibility. This mechanism will probably be useful most of all to library designers, though. We avoid deep class hierarchies and favor composition over inheritance in our application code anyway.

Optionals #

Optional is a container which may contain an element, or be empty (hence the payload is optional). You can think of it as of a collection with a maximum capacity of one. The reason such a strange object is useful is because it explicitly conveys the information that an object may be present or absent.

In Java, any object reference may be null, which sometimes causes issues with NullPointerException and other ugly errors. Since any reference is effectively optional, in order to be fully safe, all code would need to be packed with null-checks. This would make it completely unreadable and hard to write, so developers usually make assumptions about which references may be null and which may not. The reference itself does not carry such information, so errors tend to creep in. Since there is only one null value, nulls break static typing and make automated reasoning about code harder.

Types such as Optional explicitly say that a value may be present or not. If they were used consistently in all APIs, one could safely assume that a reference which is not an Optional is never null. Scala does this, but due to backwards compatibility we won’t see this in Java. Optionals are also generic types, so even if the value is absent, its type is strictly defined.

We had been using Optional class from Guava extensively in the application before, so migrating to Java Optional was pretty easy. Both APIs are quite similar, and except for changing the import statements and a few modified method names (e.g. absent() becomes empty()), Optional from Java 8 is almost a drop-in replacement for the Guava one.

Being able to easily use lambda expressions (we’ll focus on them later) makes Optionals in Java 8 much more useful than Guava Optionals in Java 7. There is only a small gain in replacing:

String cityName = getCity(location);

if (city != null) {

doSomething();

}

with

Optional<String> cityName = getCity(location);

if (city.isPresent()) {

doSomething();

}

You do get the explicit information: “beware, this might be empty”, but little more. What makes Optional truly appealing are methods such as ifPresent() and orElseThrow() along with map() and filter() which all accept lambda expressions. Lambda expressions are described more thoroughly later on, but the example below should give you a taste of using Optionals in a functional way which goes far beyond being a wrapper around null values.

Suppose you have a list of shipping service providers and you know their prices for next-day delivery. The price is

not provided if the company does not offer such service. Shipping fees are subject to taxation. Customers enter the maximum

price they are willing to pay for next-day delivery. You should return the price declared by the first company which can ship

the product in one day for the price indicated by the customer or lower, or throw an exception if no company matches.

Assuming ShippingService.getOneDayShippingFee() returns Optional

public BigDecimal priceFromFirstQualifyingService(BigDecimal maxFee, List<ShippingService> services) throws NoQualifyingServiceFoundException {

return services.stream()

.map(shippingService -> shippingService.getOneDayShippingFee())

.map(oneDayShippingFee -> oneDayShippingFee.map(fee -> fee.multiply(TAX_RATE)))

.filter(Optional::isPresent)

.map(Optional::get)

.filter(fee -> fee.compareTo(maxFee) <= 0)

.findFirst()

.orElseThrow(() -> new NoQualifyingServiceFoundException());

}

Arguably, this example would be more complex if written with standard, imperative code and null checks. You can find more on using Optionals for setting default values in a concise way in the section A matter of style. On the other hand, this example reveals some weak points of the Java 8 Optional API. In Scala we could use flatMap() on a list of Optionals in order to extract and map the contained values as well as to remove empty Optionals from the list at the same time, making this code shorter.

Still, Optional’s functional programming API is more convenient to use than that of Java collections. Since Optional is a completely new class in Java, its API is simple. For example, methods map() and filter() are defined directly in the class. This is in contrast to collection classes such as List where you have to extract a Stream first, making the code more verbose. Likewise, being forced to use collect(toList()) each time you transform a list to another list, which is common, is a nuisance. Even though there is a rationale behind the streams API (on-the-fly transformations for performance, probably some backwards-compatibility issues, too), I find Scala’s approach of having map() and filter() directly in collection classes much more convenient for the programmer. By the way, Scala allows you to optionally use views and to choose between filter() and withFilter(), so you can either materialize the filtered list, or perform lazy on-the-fly filtering like in the Stream API.

We have some internal libraries which use Guava Optionals and we didn’t want our changes to spill out of one application, so we decided to leave these libraries unchanged. This meant the need for conversion code to bridge between Guava and Java Optionals. Such code is rather confusing due to the use of two classes with the same name in one place, so it is best to wrap it inside a utility method such as:

public static <T> Optional<T> guavaToJavaOptional(com.google.common.base.Optional<T> guavaOptional) {

return Optional.ofNullable(guavaOptional.orNull());

}

Lambdas, lambdas burning bright #

In a nutshell, lambda expressions, also called functional literals or closures, allow you to treat short fragments of code as values, meaning that you can pass “a piece of code” to a method and execute it from there. It’s a very simple yet powerful concept.

A common simple use case is filtering lists according to certain criteria. Usually, you create a new list, iterate over the source list, check each element if it matches a criterion, and add it to the new list if it does. The loop itself usually takes more space than the actual logic of choosing the proper element. Functional programming simplifies such code by hiding the iteration, instead providing a single function, usually called filter() which accepts the function used to check which elements match our criteria as an argument.

It means you can replace

List<Integer> filteredList = new ArrayList<>();

for (Integer value : originalList) {

if (value > 10) {

filteredList.add(value);

}

}

return filteredList;

with

return originalList.stream().filter(value -> value > 10).collect(toList());

Scala makes it even shorter:

originalList.filter(_ > 10)

Here, value -> value > 10 (or _ > 10 in the Scala example) is a lambda expression — an anonymous function defined inline and passed as an argument to the filter() method. The somewhat longer Java code is a result of first having to transform the List to a Stream using stream() method, performing a functional transformation, and then returning the result as a list again (collect(toList()) call).

Likewise, a function called map() can be used to transform a collection to a collection whose each element is the result of applying a function to the original collection’s corresponding element. Here is an example of parsing a list of Strings into a list of Integers:

return stringList.stream().map(string -> Integer.valueOf(string)).collect(toList());

or, using method references (mentioned below):

return stringList.stream().map(Integer::valueOf).collect(toList());

Note that both filter() and map() create new collections (actually, Streams in Java 8) rather than modifying original collections.

Many applications include a surprising amount of code which you can simplify this way.

Lambdas and functional interfaces #

One very nice thing JDK engineers implemented is the possibility of using lambda expression syntax to define any anonymous class which implements an interface with only a Single Abstract Method (SAM). Such interfaces are called functional interfaces or “SAM types” in Java 8 jargon, and they are quite common in Java libraries (think of Runnable, Callable or some of the Function types found in Guava).

Now instead of:

scheduledExecutorService.schedule(new Runnable() {

@Override

public void run() {

doSomething();

}

}, ...);

you can write:

scheduledExecutorService.schedule(() -> doSomething(), ...);

Previous example is so ugly you would probably not want to use an anonymous class at all, instead moving this code to a regular class and adding even more boilerplate. With SAM syntax, a closure is used to implement the only method that needs implementing, namely run().

Being able to use lambda expressions (described below) in Java 8 makes Optionals more attractive than before. You could use transform() method in Guava’s Optional with Java 7, but this method requires a function to be passed as an argument. Before Java 8 this made it awkward to use. With function literals now available in the language, Optionals can show their true potential, and as you’ll see in the part about transforming maps, SAM syntax allows Guava to fully shine.

A matter of style #

A common task that applications handle is receiving an optional parameter and replacing it with a default value when none is provided. Since most Java APIs do not use Optional class, a missing value is marked with a null reference. There are several approaches to setting a default value (examples assume static imports for the methods used).

If-clause:

if (value == null) {

return defaultValue;

}

return value;

Objects.firstNonNull() / MoreObjects.firstNonNull() from Guava or ObjectUtils.firstNonNull() from Apache Commons:

return firstNonNull(value, defaultValue);

and now using Optional:

return ofNullable(value).orElse(defaultValue);

Personally, I prefer the snippet that uses Optional, but opinions are divided within the team. I’d be happy to learn what you think. Feel free to comment.

Functional transformations #

Using lambda expressions and stream API with functional transformations such as map() and filter() allowed us to make our code shorter and more readable. We were surprised how many pieces of code this syntax could improve. In many cases, method references came in handy and made the code even more compact. We could also get rid of Guava constructs based on FluentIterable that we had used before and replace Iterables.transform(list, SOME_FUNCTION_CONSTANT) with list.stream().map(LAMBDA_EXPRESSION).collect(toList()) etc.

By the way, we miss Iterables a little — it’s easy to transform a collection to a stream in Java 8, but getting a stream from Iterable is rather clunky. Method references would be even cooler if they could be combined with static imports or provided a shorthand for writing this::someMethod.

Simple use cases #

There are areas where Java 8 provides very nice solutions, e.g. simple mapping between DTOs and business objects:

final List<CommissionDto> commissionDtos = Lists.newLinkedList();

for (CassandraOfferCommission cassandraOfferCommission : cassandraOfferCommissions) {

commissionDtos.add(buildCommissionDto(cassandraOfferCommission));

}

return commissionDtos;

becomes (note the use of method reference):

return cassandraOfferCommissions.stream().map(this::buildCommissionDto).collect(toList());

We found cases where simple, textbook-like functional transformations perfectly matched our needs. Here is a piece of code that traverses a sorted list of price Ranges matching a criterion and returns the first matching one or throws an exception when there isn’t any:

return getRanges().stream()

.filter(range -> range.containsPrice(amount))

.findFirst()

.orElseThrow(() -> new RangeNotFoundException(String.format("No matching range found for amount %s", amount)));

But there were places where the API felt to be missing just a little bit of something to be fully satisfying. Transforming maps is painful:

quoteDetails.entrySet().stream().collect(toMap(Entry::getKey, e -> e.getValue().getFee()))

At first we thought that Java 8 would allow us get rid of Guava once and for all, but in Guava you can do this:

Maps.transformValues(quoteDetails, FeeDefinition::getFee)

Well, sorry to say, but Guava’s solution is so much more readable, even despite using static utility methods instead of “proper” object-orientation. Notice how method references play well with Guava. Since the method is defined on map’s value type, we can use a method reference, while in Java 8 code we have to work on elements of Map.Entry type which results in more code. Despite our hopes, Guava is alive and kicking.

Advanced transformations #

We really miss tuples (pairs, triples etc.), which would make some transformations easier and result in better code. In Scala, mapping and filtering maps is convenient in part because one iterates over pairs consisting of a key and a value. In Java, you get elements of type Map.Entry, which require long method names for accessing actual keys and values (getKey() and getValue()). Tuples may be risky when API designers allow them outside of their classes, resulting in crazy types like a map from pairs of string and integer into lists of triples… you get the idea. Use case classes in Scala for all external APIs, unless you are writing some really generic function such as List.zipWithIndex(). But for temporary partial results of functional transformations, tuples are very useful.

Speaking of which, we had cases where zipWithIndex would have been of great help but it’s not available in the stream API. We also had a situation where List.sliding() would have made our work much easier but it is not available in Java.

Single and nested loops #

We found quite many cases when we were not able to modify code into fully functional expressions. These were mostly cases with two or more nested loops, where the most deeply-nested expression depended both on the external and on the internal item. They ended up as forEach loops with some procedural code inside — a rather ugly solution. Scala’s for-comprehensions over two variables or simple to use tuples which could pass values from the outer to inner loop would have saved the day.

A nice thing about forEach, though, is that it does type inference, and so it can sometimes be shorter to write than the corresponding for loop. You can, for example, replace

for (String path : paths) {

...

}

with

paths.forEach({ path ->

...

});

which is just a bit shorter. You gain more with long type names, especially when complex generics come into play. In contrast to map() & co., </tt>forEach</tt> is defined directly in collection classes, so there’s no need to add stream() to the expression. We ended up replacing most of our for-loops with forEach.

In a functional frenzy, we even replaced some simple for (int i = 0; i < MAX; i++) type loops with range(0 ,MAX).map(…) and similar expressions. Here, range() and rangeClosed() are methods statically imported from IntStream. Code using ranges like this is sometimes more readable, but not always. Note that there is a separate LongStream for Longs and both are different classes than the regular Stream used for objects. You can see here that Java’s type system is not the most consistent one on the planet.

We did however, leave a few for-loops unchanged, in particular several iterations over arrays. Since arrays do not have forEach() and you have to call Arrays.stream() in order to process them with lambdas, many gains in expression length are lost. We also left regular iteration over arrays in AOP code, which we wanted to keep as simple and fast as possible.

Partitioning lists #

Tuples would have also made partitioning by a predicate much nicer. This operation resembles filtering, but instead of returning only elements that match a boolean expression, you get two separate lists: one with matches and one with non-matches. We had several use cases, but since Java’s partitioningBy() collector returns a map from Boolean to List, the resulting code was a mess, and we decided to stick with procedural code in some cases. In contrast, Scala’s List.partition() method returns two lists which makes it easier to use.

Let’s suppose our application’s client sends us a list of fees to calculate. Fee names which we can map to supported fee types should be converted to corresponding enum values. Unrecognized fee names should just be stored and passed on.

Set<ChargeType> chargeTypes = Sets.newHashSet();

Set<String> unknownCharges = Sets.newHashSet();

for (String chargeName : chargeNames) {

Optional<ChargeType> chargeType = ChargeType.fromChargeName(name);

if (chargeType.isPresent()) {

chargeTypes.add(chargeType.get());

} else {

unknownCharges.add(name);

}

}

Now, how do we make this code more functional? We would be happy to use map() to transform strings to ChargeType, but in one of the cases we still need the original string, so the lack of tuples/pairs or double loops is a real pain. We could try splitting the list first by the predicate ChargeType.fromChargeName(name).isPresent(), but then we end up with a Map<Boolean, String> which is rather inconvenient to work with. In the end, we just replaced the for-loop with an imperative forEach expression and let it go. It made the impression of something that should be very concisely expressed in a functional manner, but it felt like the solution was just around the corner all the time. We were not able to improve this code using the stream API any further.

We did, however find some areas where partitioningBy() was helpful, for example splitting price lists into default and custom price lists:

List<PriceList> allPriceLists = priceListRepository.find(day, countryCode);

Map<Boolean, List<PriceList>> defaultToPriceLists = allPriceLists.stream()

.collect(partitioningBy(PriceList::isDefaultPriceList));

List<PriceList> defaultPriceLists = defaultToPriceLists.get(TRUE);

List<PriceList> categoryPriceLists = defaultToPriceLists.get(FALSE);

A few other random observations #

- flatMap() requires a function that returns Stream which is very inconvenient and makes Optionals less useful than in Scala. Suppose you have a list of lists of Integers and want to transform each list into the first positive element in the list, or no entry if the list does not include any positive elements. So, a list such as ((-1, -2, 3), (-4, -5, -6), (7, 8, 9)) should be transformed to (3, 7). In Scala, it’s as simple as listOfLists.flatMap(x => x.find(x => x > 0)). In Java 8, the operation performed by find() can be performed by combining filter() and findFirst() but you can’t use flatMap() with the Optional returned by findFirst(), so you end up with something like: listOfLists.stream().map(list -> list.stream().filter(x -> x > 0).findFirst()).filter(Optional::isPresent).map(Optional::get).collect(toList()) Not exactly my definition of concise.

- Conversions between primitives and objects tend to be awkward. There are separate stream classes for primitives. Methods such as boxed() help a bit. Fortunately, we did not have to move between objects and primitives that much.

- You can’t perform function composition on method references, which would be cool. You can replace map(x -> f(x)) with map(this::f) but you can’t replace map(x -> f(g(x))) with map(this::f.compose(this::g)) even though there is a compose() method in the Function interface.

- If your closure would like to throw an exception, it can’t. You have to wrap your code into a try-catch block, or move it to a separate method, which contains such wrapping. Sometimes, it’s quite frustrating. It would be nice to have something like Scala’s Try class.

- Compilation errors can sometimes be confusing. On the other hand, we feared that stack traces from closures would be very complex, but in practice we hardly had to analyze any so this was not much of an issue.

- It’s nice you can now create comparators using a builder-like interface and use them to sort or find minimum / maximum easily: list.stream().collect(minBy(comparing(MyClass:getField1).thenComparing(MyClass:getField2))).

- Coding conventions are still in their infancy — sometimes we were not sure how to best format long functional expressions. We tend to add a line break after .stream() since it’s just boilerplate, and after each map(), filter() etc. except for very short expressions.

Lambda expression wrap-up #

At the end of the day, despite many shortcomings, the stream API allowed us to improve our code over Java 7, making it considerably more readable. However, one important lesson we learned is that there is no single “best” way of writing loops. What is better depends on each particular situation. Never apply changes automatically, just because closures are cool. We found cases where they were better choice than imperative code, but in some places we kept Guava transformations or even simple for-loops. Always look at each particular piece of code and consider if your change actually makes it better. The same applies, of course, to any other refactoring.

Date and Time package #

After a success with lambdas and a very smooth migration from Guava Optionals to Java 8 Optionals, we expected the new date-time package (also known as JSR-310) to be a sort of drop-in replacement for the Joda Time library we had been using so far.

We were terribly wrong.

While some classes seem to correspond to each other (e.g. ZonedDateTime being a replacement for DateTime), their APIs are completely different. Joda Time and Java 8 also parse and format dates in quite different ways. Joda is very lax and will happily parse incomplete formats: some constructors will parse into a date almost any string you provide. This is not too good for APIs, but very convenient for test code. Java 8 is much stricter and will reject anything that deviates even a bit from the expected format.

To cause even greater confusion, both libraries can parse date-time format strings, and many strings are valid in both, but have a slightly different interpretation. Hint: the number of Z letters you use for the time zone format makes a huge difference in Java 8. Also, default behavior in regard to time zones varies. We found Java 8 API to be much more verbose in most cases.

Another problem is library support. Joda has been a de facto standard for serious date-time manipulation in Java, so all major libraries provide interoperability. In order to handle the new types from Java 8 date/time API in JSON, we had to register an additional module, JSR310Module in our ObjectMapper (our company-internal application skeleton provided JodaModule registered out of the box). For Spring Data MongoDB support, we had to write custom code to provide object-to-DB mapping.

As with Optionals, we had some custom libraries, which used Joda Time, so we needed to convert between Joda and Java 8 in a few places. We also ran into issues in tests, where some methods such as assertj’s isEqualTo() provide no type safety. Some tests failed because we were comparing instances of two different classes, e.g. Joda LocalDateTime and Java LocalDateTime, but the compiler had given us no warning that a particular place needed changing, and we first saw errors at test run time.

The upside is that by going through all this date-related code (and maybe the strictness of the Java 8 date-time API) allowed us to find a bug in the code which we were previously not aware of. Well, dates and time are complex subjects.

The downside is that after some time we gave up. Refactoring to the new API took us more time than planned. Besides, we started to realize that new code was not better than original (except for using an library from the JDK instead of external one). Due to more verbosity and having to maintain compatibility with Joda-enabled libraries, it was actually somewhat worse. Given some more time, we would have been able to finish the job, but we felt it made no sense at this point. We will probably wait until all major libraries catch up and provide out-of-the-box support for Java 8 before we try again. Becoming aware of something not work well for us is also a valuable lesson.

Tests are your friends #

In this refactoring experiment we were once again able to confirm the fact that good test coverage and high quality tests are crucial to code refactoring. Whether it was Optionals, lambdas, or, most of all, date and time API changes, our modifications broke tests, caused them to fail and alerted us that something had gone wrong. Just trying to imagine what sort of bugs we would have introduced if the tests were not there sends shivers down my spine.

Summary #

We migrated a business-critical application from Java 7 to Java 8, deployed it, and have been running it in production for some time now. We think the best way to migrate to new platforms or to get started with new languages is to use them for new code, and you get such chances quite often in a microservice-based architecture compared to monolithic applications. However, refactoring an existing application allowed us to gather lots of useful knowledge and invaluable hands-on experience in a short time. We were able to collect practical data, based on our actual use cases. The new date-time API turned out to not be as easy to use as we had expected and we will be cautious when trying to use it elsewhere. We also learned where the stream API shines and where its shortcomings are. Despite some limitations, we found many of the new features compelling and useful.

We hope this summary will be helpful for others looking for their way into the Java 8 world.