Migrating to Service Mesh

This year Allegro.pl turns 21. The company, while serving millions of Poles in their online shopping, has taken part in many technological advances. Breaking the monolith, utilising public cloud offerings, machine learning, you name it. Even though many technologies we use might seem as just following the hype, their adoption is backed by solid reasoning. Let me tell you the story of a project I’ve had the privilege of working on.

The why #

I’m not going to discuss the background behind a Service Mesh as there are plenty of articles on this subject already. I’ve also written a piece (in Polish) specifically about why we decided to benefit from this approach.

Let’s just simply list what we were looking for:

- Taking the common platform code (service discovery, load balancing, tracing) out of libraries.

- Taking the mTLS logic out of the libraries and application code.

- Unifying the permissions for service-to-service communication.

- Unifying the HTTP level observability of service-to-service traffic.

The complexity #

An online marketplace, such as Allegro.pl, is a complex beast. There are many segments of the business that evolve at their own pace and utilise different technologies. Our services (mostly JVM-based) run mainly on Mesos/Marathon setup as the on-premise private cloud solution. We’re just beginning with migrating services to Kubernetes (abbreviated as k8s). We also utilise the public cloud when it makes sense (and need to integrate it with our stack). Some of the services are packaged in Docker. But our architecture is not just microservices. We also have:

- a few edge solutions in place (API Gateways, Edge Proxies, Backends for Frontends, etc.),

- external load balancers,

- reverse proxies,

- a distributed message broker,

- several services running on VMs,

- a Hadoop cluster with batch jobs,

- and an infamous, taken-apart, but still running, PHP monolith.

The how #

The journey began at the end of 2018. At the time we evaluated existing solutions and found out most of the technology is aimed only at k8s. We tried istio, which turned out to require the network isolation only containers on k8s provide. We needed a custom control plane to glue all things together. And we went for Envoy as the most stable and advanced L7 proxy that would fit our needs. Envoy is written in C++ and provides a predictable and stable latency due to its memory management without garbage collection and many impressive architectural decisions (e.g. the threading model).

Control plane #

My team has been responsible for providing JVM developers with a framework integrating the platform elements. We had the most experience in JVM-based languages: Java and Kotlin. And we knew some Go. The Envoy team hosted two implementations of the basis for a control plane: one written in Go and another in Java. We decided to write our solution in Kotlin and open-sourced it. Under the hood we use the java-control-plane library, which we’ve become maintainers of.

Service discovery in our platform has been based on Hashicorp’s Consul. We already had efficient integration with Consul written in Java, which we leveraged in our project. We called our control plane envoy-control.

Because it uses a high-level language, i.e. Kotlin and the JVM landscape of tools, we were able to do some interesting things with it, such as reliability testing with Testcontainers. These tests emulate several possible production failures and they can be run quickly on a laptop. This test suite saves us a lot of time.

Additionally, after some time operating Envoy and envoy-control, we all agreed that we needed an admin panel. So we implemented a GUI component with a backing service that eases operations. From a central place we can:

- list all instances for a service,

- diagnose a particular Envoy instance (fetch config dump, statistics),

- change particular Envoy instance’s logging level,

- fetch envoy-control’s snapshots of configuration before XDS processing,

- compare envoy-control instances to validate their consistency.

Data plane #

The services in our platform are deployed via an internal deployment component, which reads a YAML descriptor file that sits in the root of each service’s repository. The deployment metadata is made available to each service’s environment, which then is read by another component, which we called envoy-wrapper. It prepares a basic Envoy configuration file and launches Envoy. The rest is handled by the XDS protocol and communication with envoy-control to stream Envoy’s configuration continually. Among the metadata sent to envoy-control, services list their dependencies. Listing needed services limits the amount of data Envoy requires. Some privileged services, like Hadoop executors, require the data for all available services, so there’s a case for that, too.

We also run Envoy on VMs that are configured using Puppet. We use the hot restart capabilities of Envoy to power these backends.

The status #

When we launch a service with Envoy as a sidecar, we do a trick with service registration in Consul. The port of service’s Envoy is registered instead of the service’s port. Using this technique we accomplished the first step of the migration – moving ingress traffic of services to Envoy.

In case of egress traffic, things were not as simple. Because of the lack of containerised network isolation, iptables would have been a nightmare to maintain and debug. We went for a long strategy for introducing egress via Envoy. We made a decision that all services would need to update their libraries to ones that support explicit HTTP clients’ proxying via Envoy. We then asked all the teams to do so.

This decision was a very important step in the migration. We didn’t want to break existing platform features, such as load balancing implemented in the libraries. And we wanted to move in increments by showing the value of Service Mesh early on and cause a snowball effect. In the meantime, we were adding new features in an agile way.

An explicit proxy was key to a smooth migration. In order to handle particular use-cases that were not yet implemented in the Service Mesh or needed a particular type of handling, we created a special HTTP client interceptor. This interceptor would make decisions whether requests should be proxied or not. The decisions were based on a set of flags, which we could override for deployments with a high level of control and make careful rollouts.

An example of when we couldn’t proxy traffic just yet were cases when mTLS was used via application code. We didn’t want to break the security provided by the existing setup. But when we are ready, we will just flip a flag, then redeploy, and the traffic flows through Envoy.

Speaking of security, to authenticate Envoys, we don’t use SDS for certificates distribution. Our hosts are equipped with certificates which are provided by the deployment component. We plan to use these certificates to authenticate Envoys as the services to which the certificates belong to. Having that, we can use the permissions imposed via access rules that Envoy executes to restrict service-to-service communication.

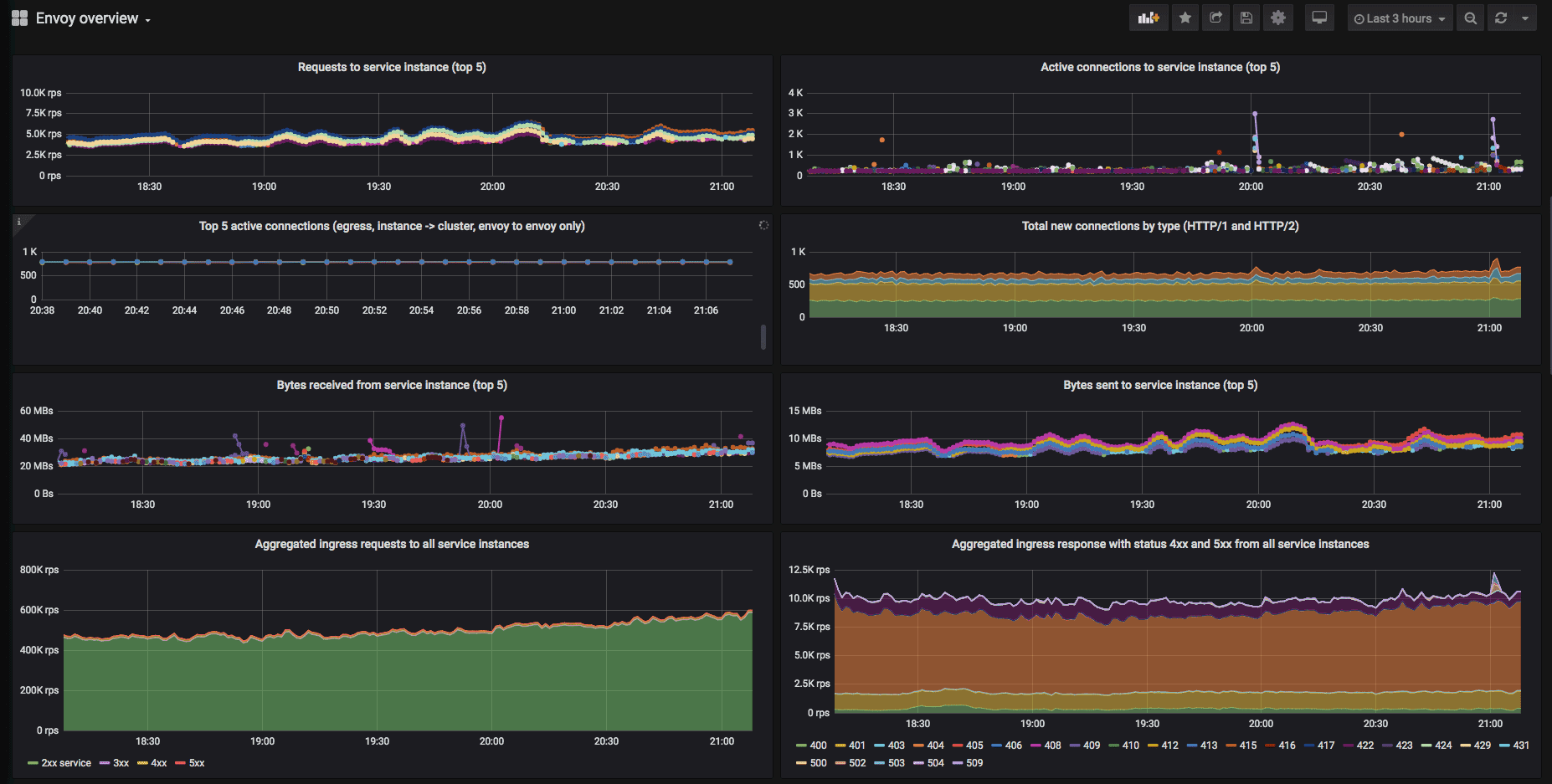

At the moment of writing, we have 830 services accepting ingress traffic via Envoy. Almost 500 of them communicate via Envoy for egress traffic. Last week we observed peaks of > 620,000 req/s of ingress traffic and > 230,000 req/s of egress traffic inside the mesh. We can see a high-level overview of traffic in Grafana to get a glimpse of what’s happening.

Application developers can see their particular service traffic characteristics on a dedicated dashboard. When needed, it’s even possible to investigate a specific Envoy instance from the metrics perspective.

In the process we’ve been able to keep existing routing solutions and load balancing across our data centers, including subset selection based on canary releases, particular service tags, or instance weights in Consul.

The bumps #

By introducing the proxy component we have experienced many issues during the migration. Just to name a few:

-

Envoy is super strict with HTTP. For instance, we needed to update many places to be case insensitive towards header names.

-

We saw a sudden rise in 503s across many deployments. The reasons happened to be either connection timeouts, which would otherwise not have been interpreted as application level issues and simply retried by clients, or race conditions in our service registry mechanism, which would sometimes flap.

-

When we integrated Hadoop we started experiencing an issue when an Envoy would get stuck while receiving configuration and would eventually be unusable. This was caused by entering a so-called “warming clusters” state. It happened when an entire service would go away, which is not a very rare case in our environment. We refreshed an older contribution and made additional improvements to java-control-plane to fix our particular issue.

-

We also decided early on to encourage developers to proxy traffic to domains via Envoy. By domains we mean destinations that are not part of the mesh, but are represented by DNS addresses (external or internal domains). This caused a few surprises, such as Envoy not supporting the CONNECT HTTP method or H2 upgrade mechanism.

-

Another interesting issue we found was misleading Envoy stats after we deployed Envoy next to our PHP monolith. The gauges had the values from the previous instance after a hot restart, which made us worry as to whether the services were fine.

The evolution #

Deploying a Service Mesh in a complex environment has been a massive transformation and a lot of work was put in by hundreds of application developers. The migration helped teams reduce technical debt. This reduction was a byproduct of migrating to the latest versions of libraries that provided Service Mesh support. The off–the–shelf shiny control planes created for k8s are great for greenfield projects, but are out of reach of many organisations with existing non-homogenous stacks. Matt Klein, the main creator of Envoy, recently described this fact in a blog post. I hope this story is helpful and shows how a production deployment looks from the birds-eye view in such a setting. What we’re looking at next are ways to integrate our existing services with k8s native solutions to create a seamless experience for our users. We’ve made significant work on stabilising and optimizing our control plane, which now hosts over 5,000 Envoys in production, some of which require the configuration for all instances of nearly 1,000 services registered in Consul. What we have on our roadmap is the vision of revisiting distributed tracing without the need to modify the libraries and having developers migrate again. That can be made possible with Envoy.

(And) The thanks #

Envoy’s community has been very supportive. We managed to get help when we needed and our Pull Requests have been integrated quickly. Envoy releases come at a great pace and we’re extracting tremendous amount of observability data without almost any impact on the bulk of our service-to-service communication. The learning experience has been absolutely invaluable to myself and to the amazing team I have the privilege to be working with. We are application developers, yet we have absorbed so much networking and protocol knowledge throughout the process. We continue giving back to the community and look forward to hearing about your experiences with Service Meshes in the comments.