Managing Frontend in the Microservices Architecture

Microservices

are now the mainstream approach for scalable systems architecture.

There is little controversy when we are talking about designing backend services.

Well-behaved backend microservice should cover one

BoundedContext

and communicate over the REST API.

Things get complicated when we need to

use microservices as building blocks for a frontend solution.

How to build a consistent website or a mobile app

using tens or sometimes hundreds of microservices?

In this post we describe our current web frontend approach and the new one, meant as a small revolution.

Doing frontend in the microservices world is tricky #

Our users don’t care how good we are at dividing our backend into microservices. The question is how good we are at integrating them in a user’s browser.

Typically, to process one HTTP request sent by a user, we need to collect data from many microservices. For example, when a user runs a search query on our site, we send him the Listing page. This page collects data from several services: AllegroHeader, Cart, Search, Category Tree, Listing, SEO, Recommendations, etc. Some of them provide only data (like Search) and some provide ready-to-serve HTML fragments (like AllegroHeader). Each service is maintained by a separate team with various frontend skills.

Developing modern frontend isn’t easy. Following aspects are involved:

- Classical SOA-style data integration, often done by a dedicated service, called Backend for Frontends or Edge Service.

- Managing frontend dependencies (JS, CSS, etc.) required by various HTML fragments.

- Allowing interactions between HTML fragments served by different services.

- Consistent way of measuring users’ activities (traffic analytics).

- Content customization.

- Providing tools for A/B testing.

- Handling errors and slow responses from backend services.

- There are many frontend devices: web browser, mobile… Smart TV and PlayStation® are waiting in the queue.

- Offering excellent UX to all users (omnichannel).

The last two things are most important and most challenging. This means that your frontend applications should be consistent, well integrated and smooth. Even if they shouldn’t necessarily be monolithic they should look like a monolith.

Let me give you an example from Spotify. You can listen to the music on a TV set using PS4 Spotify app. Then you can switch to Spotify app running on your laptop. Both apps give you a similar look and feel. Not bad, but do you know that you can control what PS4 plays by clicking on your laptop? It just works. That’s really impressive.

There are two opposite approaches to modern frontend architecture.

- Monolith approach

- Frankenstein approach

Monolith approach is dead simple: one frontend team creates and maintains one frontend application, which gathers data from backend services using REST API. This approach has one huge advantage, if done right, it provides excellent user experience. Main disadvantage is that it doesn’t scale well. In a big company, with many development teams, single frontend team could become a development bottleneck.

In Frankenstein approach (shared nothing) approach, frontend application is divided into modules and each module is developed independently by separate teams.

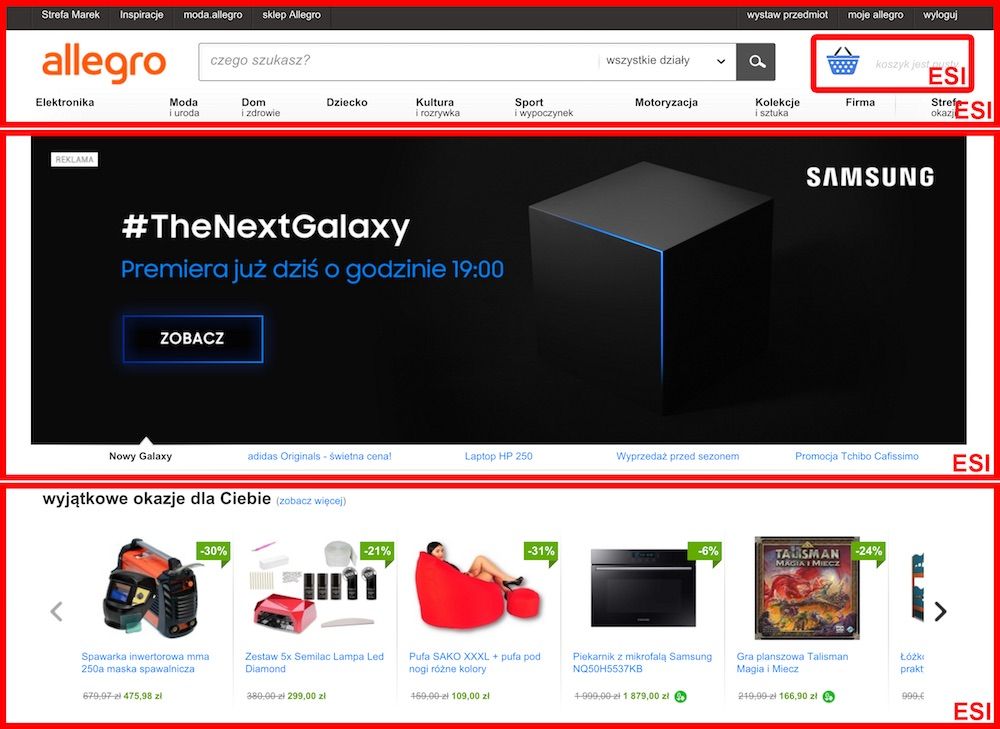

In Web applications modules are HTML page fragments (like AllegroHeader, Cart, Search). Each team takes whole responsibility for their product. So a team develops not only backend logic but also provides an endpoint which serves HTML fragment with their piece of frontend. Then, HTML page is assembled using some low level server-side includes technology like ESI tags.

This approach scales well, but the big disadvantage is a lack of consistency on the user side. Seams between page fragments become visible, page-level interactions are limited. Even in page scope, each page fragment may look, or even worse, behave in a different way. Pretty much like the Frankenstein monster.

Between Monolith and Frankenstein there is a whole spectrum of possible architectures. What we want to build is the desirable middle ground between these two extremes.

Next, we describe the current approach at Allegro, which is close to the Frankenstein extreme and the new solution, which goes more into the monolith direction.

Current approach at Allegro #

Nowadays at Allegro we have to struggle with the legacy monolithic application (written in PHP) and with many new microservices (written mostly in Java). Everything is integrated by Varnish Cache — web application accelerator (a caching HTTP reverse proxy).

Varnish and its ESI LANG features allow us to merge a lot of different parts of our platform into one website. Therefore any page (or a page fragment) at Allegro can be a separate application. For example, main page is composed in the following way:

Our Varnish farm also defines and greatly improves our overall performance. Varnish servers are exposed to users and they cache all requests for static content. We often say that we are hiding behind Varnish to survive the massive traffic from our users.

Varnish really hit the bull’s-eye.

Below, we describe one page fragment, included in each page — the AllegroHeader.

AllegroHeader is a service that returns a complete, self-contained page fragment along with all needed JS and CSS files — so it can be easily included using the ESI tag at the beginning of any webpage. Under the hood it collects data from a few other services like category service or cart service. It integrates the search box and it’s responsible for top level messages (cookies policy warning, under maintenance banner).

What has gone wrong? #

Each page fragment comes with its own set of frontend assets: CSS, JavaScripts, fonts and images. At the page level, it sometimes leads to duplications and version conflicts. Many page fragments depend implicitly on assets provided by the AllegroHeader.

But what if we want to create a page without any AllegroHeader at all? Or even worse — how to handle two different versions of React within a single page?

Current approach based on Varnish server-side includes is flexible, scalable and easy to develop but unfortunately, it’s hard to maintain.

Moreover, because every page fragment is a separate web application, it’s really hard to ensure consistent look and feel on the website level.

We just had to think of a better way…

OpBox project — the New Frontend solution #

So Box is the main concept in our solution. What is Box after all?

- Box is a reusable, high-level frontend component.

- Box is feedable from a REST/JSON data source.

- Box can have slots. In each slot you can put more Boxes.

- Box can be rendered conditionally (for example, depending on A/B test variant).

- Page is assembled from Boxes.

OpBox principles #

Below, we describe principles of OpBox architecture and functionality. Most of them are already implemented and battle-tested. Last two are in the design phase.

Dynamic page creation (CMS-like)

Pages are created and maintained

by non-technical users in our Admin application.

Reusable components

Each page is assembled from boxes like AllegroHeader, ShowCase, OfferList, Tabs.

Boxes are configured to show required content, typically provided via REST API by backend services.

Separating View from Data Sources

Box is a high-level abstraction. It joins two things:

- Frontend design (often referred to as a View). Concrete View implementation is called frontend component. For example, our ShowCase box has two frontend implementations: Web and Mobile.

- Data-source (REST service) which feeds data for frontend components. One component can be fed by any data-source as soon as its API matches the Box contract. For example, Offer component knows how to present a nice offer box with offer title, price, image and so on. Since Offer component is decoupled from backends by the Box contract abstraction, it can show offers from many sources: Recommendations, Listing or Ads services.

Conditional content

Boxes can be rendered conditionally as a way to provide content customization.

Various types of conditions are implemented:

- date from/to condition,

- A/B test condition,

- condition based on user profile.

For example, page editor can prepare two versions of given box, one for male users and another for female users. At runtime, when page is rendered, user’s gender is identified and one of these two boxes is pruned from the boxes tree.

Consistent traffic analytics

Basic traffic analytics is easy to achieve. It’s enough to include a tracking script in

the page footer. When a page is opened by a user, the script reports a PageView event.

What we need is fine-grained data:

- BoxView event — when box is shown in a browser viewport.

- BoxClick event — when users click on a link which navigates them from one box to another (for example Recommendation Box can emmit a BoxClick event when users click on one of the recommended products).

Once we have this data, we can calculate click-through rate (CTR). for each box. CTR is valuable information for page editors as it helps them to decide which boxes should be promoted and which should be removed from a page.

Multi-frontend

One of the OpBox key features is separating page definitions

from frontend renderers.

Page definition is a JSON document containing the page structure and data (content).

It’s up to the renderer how the page is presented to frontend users.

For now, we have two renderers: Web — responsible for serving HTML and Mobile — responsible for presenting the same content in the Android app.

One place for integrating backend services through REST API

OpBox Core does the whole data integration job

and sends complete page definitions to frontend renderers.

It’s a great advantage for frontend developers. They can treat OpBox Core as the single point of contact and the facade to various backend services.

Future: component Event Bus

There are many use cases when we want Boxes to interact with each other.

For example, our Search page lets user search through offers available on Allegro.

Search results are shown by the Listing box.

Below we have Recommendations box which shows some offers, possibly related with the search query.

What if we would like to remove an offer from Recommendations box when it happens to be already shown by Listing box? One of the possible solutions is to implement such interactions at the frontend side.

Desired solution would let rendered Boxes to talk to each other via a publish-subscribe message bus, e.g.:

“Hi, I’m Listing box, I’ve just arrived to a client’s browser to show offers A, C and X.”

“Hi, I’m Recommendations box,

I’m here for a while and I’m showing offers D, E and X. Ouch! Looks like I’m supposed

to replace X with something different.”

Future: dependency management

Each page is assembled from frontend components developed by different

teams.

Since we don’t force frontend developers to use any particular technology,

each component requires its own dependency set of various kind:

CSS, JS libraries, fonts and so on.

Reconciliation of all of those dependency sets is kind of advanced topic and to be honest, we don’t have any well-thought-out plan for this yet.

How we did it #

OpBox system is implemented in microservice architecture. As you can see below, it consists of four sub-systems: Core, Web, Admin and Mobile.

OpBox Core #

Primary responsibility of OpBox Core is serving page definitions for frontend renderers. Moreover, Core provides an API to OpBox Admin for page management (creating, editing, publishing).

Core is the only stateful service in the OpBox family. It stores page definitions in MongoDB and box types in Git (box types are explained below).

Since Core is responsible for serving page definitions it also manages the page routing and the toughest work — fetching data from backend services. That’s the content to be injected into Boxes.

We’ve put a lot of effort into making Core high-performing, fault-tolerant and asynchronous. We’ve chosen Java and Groovy to implement it. Core is the only gateway for frontend renderers to our internal backend services.

Box types

Each Box has a type — it’s the definition that describes data parameters required

by the Box and also defines a list of named slots. Slot is a placeholder for embedding child boxes.

We use (JSON Schema) to define parameter types.

Here is an example of the Showcase Box — along with its type and the type of the data parameter that it uses.

Showcase Box type:

{

"slots": [],

"parameters": [

{

"name": "allegro.box.showcase",

"type": {

"name": "CUSTOM",

"typeName" : "allegro.type.showcasesList"

},

"description": "Showcase box",

"required": false

}

],

"nameRequired" : true

}

Showcase data parameter type:

{

"title": "allegro.showcasesList",

"description": "showcases list",

"type": "array",

"items": {

"description": "showcase",

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"imageUrl": {

"type": "string"

},

"imageAlt": {

"type": "string"

},

"linkUrl": {

"type": "string"

}

}

}

}

Rendered Showcase Box:

Data-source type is our way to specify underlying backend microservice. It contains: service URL in Service Discovery, input parameters, timeout and caching configuration. For example:

{

"url": "service://opbox-content/teasers",

"parameters": [

{

"type": {

"name": "INTEGER"

},

"name": "id",

"description": "article identifiers",

"required": true

}

],

"dataType": "allegro.article.teasers",

"timeoutMillis": 1500,

"allowCustomParameters": false,

"ttlMillis": 60000

}

OpBox Web renderer #

Web renderer is responsible for handling HTTP requests. From the Web renderer’s point of view, page rendering process can be decomposed into the following steps:

- HTTP request for a given URL is received.

- OpBox Core is asked for a page definition for a given URL.

- OpBox Core sends a page definition which contains page matadata and the Boxes tree. Each Box is filled with data gathered by Core from backend microservices.

- Web renderer traverses the Boxes tree and for each Box:

- Proper component implementation is found in our internal repository (matched by the Box type name).

- Component’s

render()function is called with box parameters passed as an argument. render()result is appended to the HTTP response.

We’ve implemented Web renderer in ES6 on NodeJS platform. Components are implemented as NPM packages and they are published to our internal Artifactory.

OpBox Mobile renderer library #

One of our requirements was support for mobile platforms. We’ve created an Android library for rendering pages in the same way as Web renderer does but using native mobile code. When OpBox editor creates a web page he doesn’t have to care about its mobile version. His page should be available both on website and on mobile app.

This way mobile developers can improve user experience using the same component definitions. By the way — now we can update our pages in your phone instantly ;) (without deploying the new version of the mobile app)

OpBox Mobile Adapter #

We wanted to treat all rendering channels equally so we’re providing one REST API for retrieving page definitions from Core. We’ve created an adapter which transforms the Core API to the mobile friendly version. Its main responsibilities are: converting JSON to more concise form, filtering out any mobile-irrelevant data, adding deep linking feature and filtering all boxes that are not supported on mobile app.

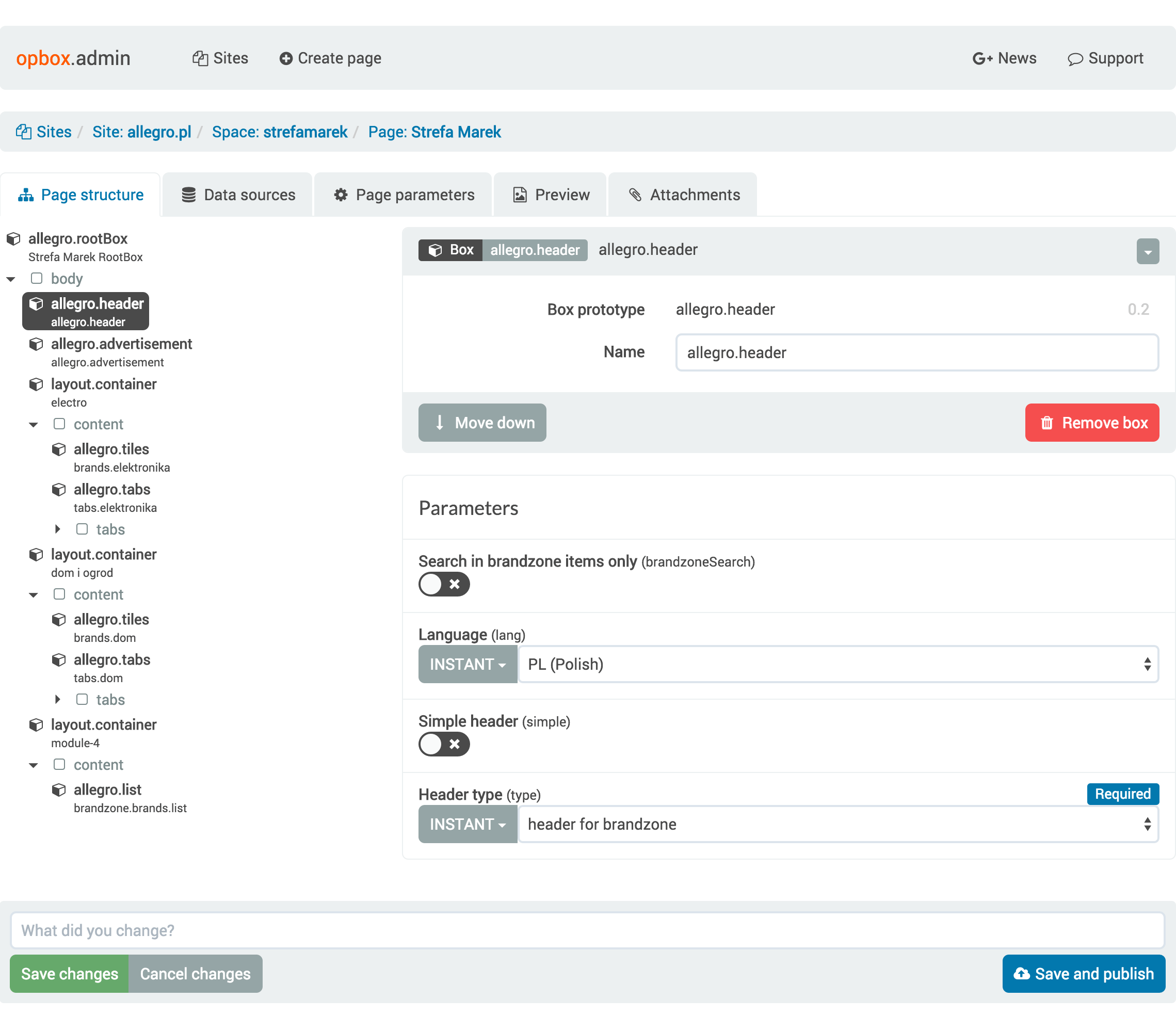

OpBox Admin #

Simultaneously, we are developing an Admin application for page editors.

It’s a stateless GUI built on top of the Core REST API. In OpBox Admin our editors create and maintain pages and they manage page routing and publication criteria.

We’ve implemented OpBox Admin using ES6, NodeJS and React.

Here you can see the sample screen of our Admin GUI:

Final thoughts #

Currently some of our marketing campaigns are published with OpBox. The solution has been battle-tested and we are planning to migrate more Allegro pages into OpBox components. We hope to share our OpBox project with the open source community in near future.