Writing a very fast cache service with millions of entries in Go

Recently our team has been tasked to write a very fast cache service. The goal was pretty clear but possible to achieve in many ways. Finally we decided to try something new and implement the service in Go. We have described how we did it and what values come from that.

Table of contents: #

Requirements #

According to the requirements, our service should:

- use HTTP protocol to handle requests

- handle 10k rps (5k for writes, 5k for reads)

- cache entries for at least 10 minutes

- have responses time (measured without time spent on the network) lower than

- 5ms – mean

- 10ms for 99.9th percentile

- 400ms for 99.999th percentile

- handle POST requests containing JSON messages, where each message:

- contains an entry and its ID

- is not larger than 500 bytes

- retrieve an entry and return int via a GET request immediately after the entry was added via a POST request (consistency)

In simple words our task was to write a fast dictionary with expiration and REST interface.

Why Go? #

Most microservices at our company are written in Java or another JVM based language, some in Python. We also have a monolithic, legacy platform written in PHP but we do not touch it unless we have to. We already know those technologies but we are open to exploring a new one. Our task could be realized in any language, therefore we decided to write it in Go.

Go has been available for a while now, backed by a big company and a growing community of users. It is advertised as a compiled, concurrent, imperative, structured programming language. It also has managed memory, so it looks safer and easier to use than C/C++. We have quite good experience with tools written in Go and decided to use it here. We have one open source project in Go, now we wanted to know how Go handles big traffic. We believed the whole project would take less than 100 lines of code and be fast enough to meet our requirements just because of Go.

The Cache #

To meet the requirements, the cache in itself needed to:

- be very fast even with millions of entries

- provide concurrent access

- evict entries after a predetermined amount of time

Considering the first point we decided to give up external caches like Redis, Memcached or Couchbase mainly because of additional time needed on the network. Therefore we focused on in-memory caches. In Go there are already caches of this type, i.e. LRU groups cache, go-cache, ttlcache, freecache. Only freecache fulfilled our needs. Next subchapters reveal why we decided to roll our own anyway and describe how the characteristics mentioned above were achieved.

Concurrency #

Our service would receive many requests concurrently, so we needed to provide concurrent access to the cache.

The easy way to achieve that would be to put sync.RWMutex in front of the cache access function to ensure that only one goroutine could modify it at a time.

However other goroutines which would also like to make modifications to it, would be blocked, making it a bottleneck.

To eliminate this problem, shards could be applied. The idea behind shards is straightforward. Array of N shards is created,

each shard contains its own instance of the cache with a lock. When an item with unique key needs to be cached a

shard for it is chosen at first by the function hash(key) % N. After that cache lock is acquired and a write to the cache takes place.

Item reads are analogue. When the number of shards is relatively high and the hash function returns

properly distributed numbers for unique keys then the locks contention can be minimized almost to zero.

This is the reason why we decided to use shards in the cache.

Eviction #

The simplest way to evict elements from the cache is to use it together with FIFO queue. When an entry is added to the cache then two additional operations take place:

- An entry containing a key and a creation timestamp is added at the end of the queue.

- The oldest element is read from the queue. Its creation timestamp is compared with current time. When it is later than eviction time, the element from the queue is removed together with its corresponding entry in the cache.

Eviction is performed during writes to the cache since the lock is already acquired.

Omitting Garbage Collector #

In Go, if you have a map, garbage collector (GC) will touch every single item of that map during mark and scan phase. This can cause a huge impact on the application performance when the map is large enough (contains millions of objects).

We ran few tests on our service in which we fed the cache with millions of entries, and after that we started to send requests to some unrelated REST endpoint doing only static JSON serialization (it didn’t touch the cache at all). With an empty cache, this endpoint had maximum responsiveness latency of 10ms for 10k rps. When the cache was filled, it had more than a second latency for 99th percentile. Metrics indicated that there were over 40 mln objects in the heap and GC mark and scan phase took over four seconds. The test showed us that we needed to skip GC for cache entries if we wanted to meet our requirements related to response times. How could we do this? Well, there were three options.

GC is limited to heap, so the first one was to go off-heap.

There is one project which could help with that, called offheap.

It provides custom functions Malloc() and Free() to manage memory outside the heap.

However, a cache which relied on those functions would need to be implemented.

The second way was to use freecache. Freecache implements map with zero GC overhead by reducing number of pointers. It keeps keys and values in ring buffer and uses index slice to lookup for an entry.

The third way to omit GC for cache entries was related to optimization presented in Go version 1.5

(issue-9477). This optimization states that if you use a map

without pointers in keys and values, then GC will omit it’s content. It is a way to stay on heap and to omit GC for entries in the map.

However, it is not the final solution because basically everything in Go is built on pointers:

structs, slices, even fixed arrays. Only primitives like int or bool do not touch pointers. So what could we do with map[int]int?

Since we already generated hashed key in order to select proper shard from the cache (described in Concurrency)

we would reuse them as keys in our map[int]int. But what about values of type int? What information could we keep as int?

We could keep offsets of entries. Another question is where those entries could be kept in order to omit GC again?

A huge array of bytes could be allocated and entries could be serialized to bytes and kept in it. In this respect,

a value from map[int]int could point to an offset where an entry has it’s beginning in the proposed array. And since FIFO queue was used

to keep entries and control their eviction (described in Eviction), it could be rebuilt and based on a huge bytes array

to which also values from that map would point.

In all presented scenarios, entry (de)serialization would be needed. Eventually, we decided to try the third solution, as we were curious if it was going to work and we already had most elements – hashed key (calculated in shard selection phase) and the entries queue.

BigCache #

To meet requirements presented at the beginning of this chapter, we implemented our own cache and named it BigCache. The BigCache provides shards, eviction and it omits GC for cache entries. As a result it is very fast cache even for large number of entries.

Freecache is the only one of the available in-memory caches in Go which provides that kind of functionality. Bigcache is an alternative solution for it and reduces GC overhead differently, therefore we decided to share with it: bigcache. More information about comparison between freecache and bigcache can be found on github.

HTTP server #

Memory profiler shows us that some objects are allocated during requests handling. We knew that HTTP handler would be a hot spot of our system. Our API is really simple. We only accept POST and GET to upload and download elements from cache. We effectively support only one URL template, so a full featured router was not needed. We extracted the ID from URL by cutting the first 7 letters and it works fine for us.

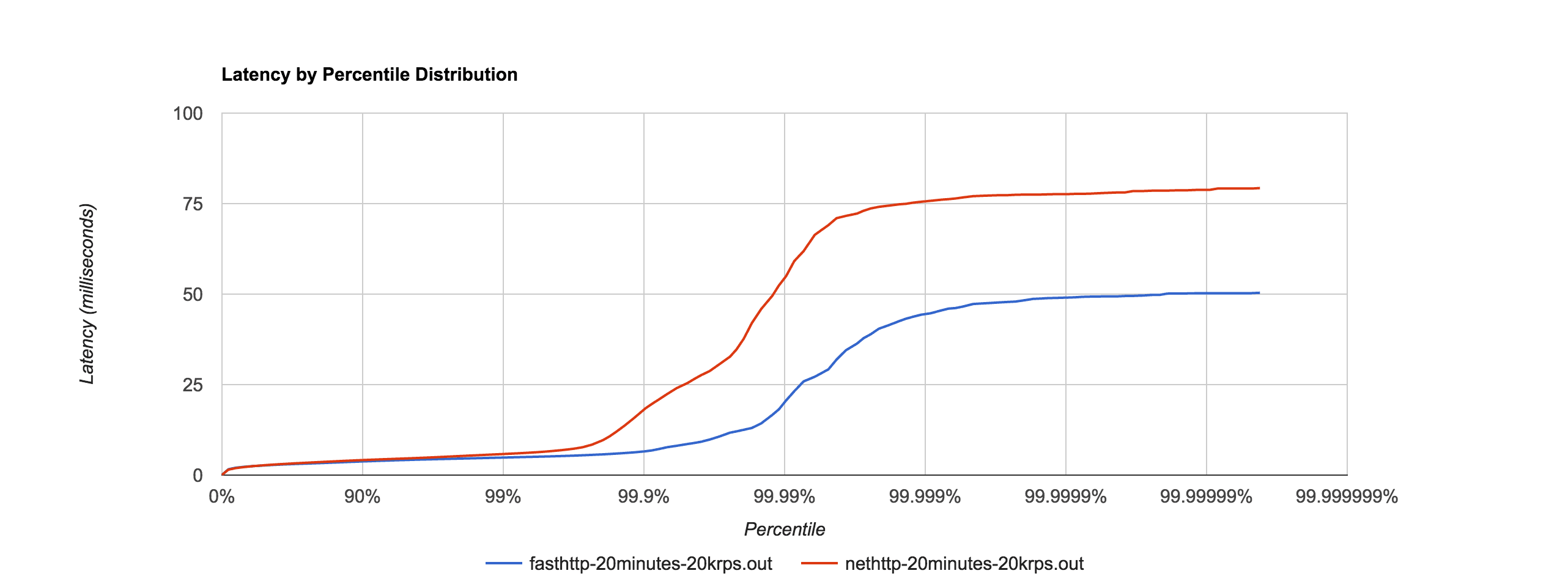

When we started development, Go 1.6 was in RC. Our first effort to reduce request handling time was to update to the latest RC version. In our case performance was nearly the same. We started searching for something more efficient and we found fasthttp. It is a library providing zero alloc HTTP server. According to documentation, it tends to be 10 times faster than standard HTTP handler in synthetic tests. During our tests it turned out it is only 1.5 times faster, but still it is better!

fasthttp achieves its performance by reducing work that is done by HTTP Go package. For example:

- it limits request lifetime to the time when it is actually handled

- headers are lazily parsed (we really do not need headers)

Unfortunately, fasthttp is not a real replacement for standard http. It doesn’t support routing or HTTP/2 and claim that could not support all HTTP edge cases. It’s good for small projects with simple API, so we would stick to default HTTP for normal (non hyper performance) projects.

JSON deserialization #

While profiling our application, we found that the program spent a huge amount of time on JSON deserialization.

Memory profiler also reported that a huge amount of data was processed by json.Marshal. It didn’t surprise us.

With 10k rps, 350 bytes per request could be a significant payload for any application. Nevertheless, our goal was speed,

so we investigated it.

We heard that Go JSON serializer wasn’t as fast as in other languages. Most benchmarks were done in 2013, so before 1.3 version. When we saw issue-5683 claiming Go was 3 times slower than Python and mailing list saying it was 5 times slower than Python simplejson, we started searching for a better solution.

JSON over HTTP is definitely not the best choice if you need speed. Unfortunately, all our services talk to each other in JSON, so incorporating a new protocol was out of scope for this task (but we are considering using avro, as we did for Kafka). We decided to stick with JSON. A quick search provided us with a solution called ffjson.

ffjson documentation claims it is 2-3 times faster than standard json.Unmarshal, and also uses less memory to do it.

| json | 16154 ns/op | 1875 B/op | 37 allocs/op |

| ffjson | 8417 ns/op | 1555 B/op | 31 allocs/op |

Our tests confirmed ffjson was nearly 2 times faster and performed less allocation than built-in unmarshaler. How was it possible to achieve this?

Firstly, in order to benefit from all features of ffjson we needed to generate an unmarshaller for our struct. Generated code is in fact a parser that scans bytes,

and fills objects with data. If you take a look at JSON grammar you will discover it is really simple.

ffjson takes advantage of knowing exactly what a struct looks like, parses only fields specified in the struct and fails fast whenever an error occurs.

Standard marshaler uses expensive reflection calls to obtain struct definition at runtime.

Another optimization is reduction of unnecessary error checks. json.Unmarshal will fail faster performing fewer allocs, and skipping reflection calls.

| json (invalid json) | 1027 ns/op | 384 B/op | 9 allocs/op |

| ffjson (invalid json) | 2598 ns/op | 528 B/op | 13 allocs/op |

More information about how ffjson works can be found here. Benchmarks are available here

Final results #

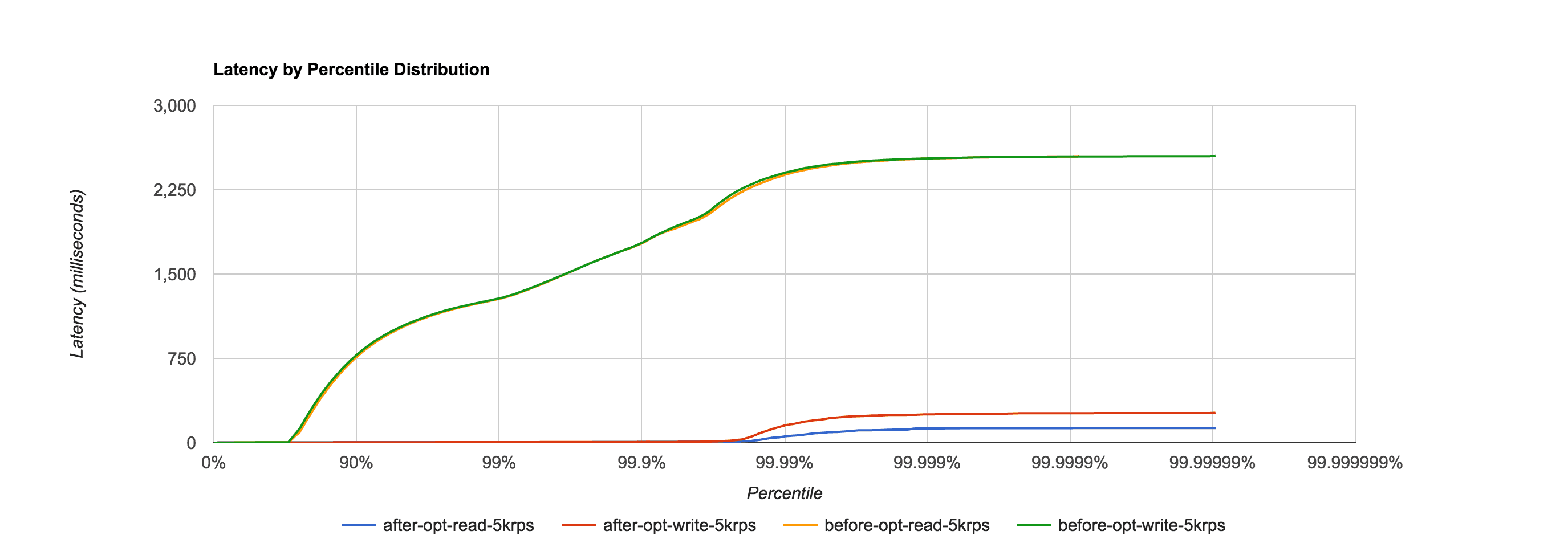

Finally, we sped up our application from more than 2.5 seconds to less than 250 milliseconds for longest request. These times occur just in our use case. We are confident that for a larger number of writes or longer eviction period, access to standard cache can take much more time, but with bigcache or freecache it can stay on milliseconds level, because the root of long GC pauses was eliminated.

The chart below presents a comparison of response times before and after optimizations of our service. During the test we were sending 10k rps, from which 5k were writes and another 5k were reads. Eviction time was set to 10 minutes. The test was 35 minutes long.

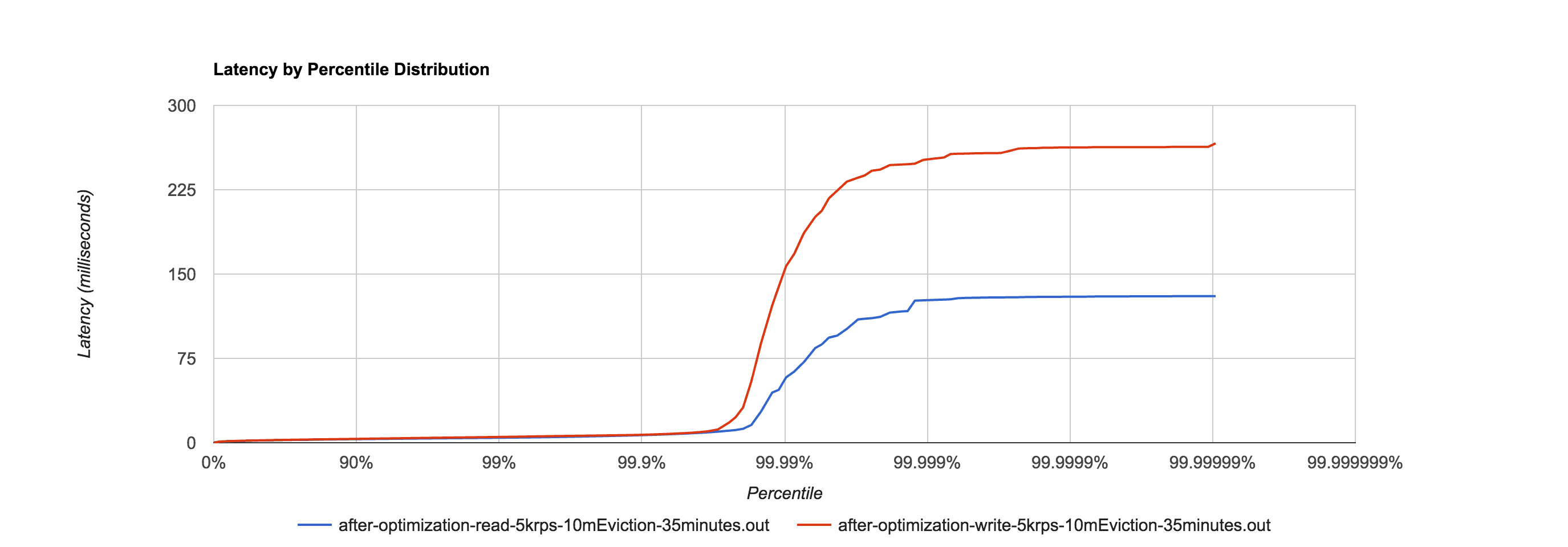

Final results in isolation, with the same setup as described above.

Summary #

If you do not need high performance, stick to the standard libs. They are guaranteed to be maintained, and have backward compatibility, therefore upgrading Go version should be smooth.

Our cache service written in Go finally met our requirements. Most of the time we spent figuring out that GC pauses can have a huge impact on application responsiveness because of millions of objects under its control. Fortunately, caches like bigcache or freecache solve this problem.