Are code reviews worth your time?

Code reviews play an important role in how we develop software at Allegro. All code we developers write is reviewed by our peers. If you apply for a job with us, we may ask you to review a sample piece of code during your interview. A code review done right carries a lot of value, but if done wrong it can become a waste of time. In this article I will describe what I think makes a good code review, how reviews have evolved over time at the teams I worked with and what you can do in order to make code reviews worthwhile.

Note that the term code review is sometimes used to describe a very formal meeting which takes place once in a while and involves a lot of people and bureaucracy. This is absolutely not the kind of code review I’m talking about here. What I am talking about is a lightweight process in which every chunk of code is reviewed by members of the team before it is merged into the master branch and which is a daily part of the development cycle.

Why? #

Before delving into the details of how to do something, you should ask yourself whether, and why it should be done at all. Broadly speaking, there are two main goals of code reviews:

- improving software quality, and

- spreading knowledge within the team

The first one is probably quite intuitive, but I think it is the second one which really shines in the long run. It helps ensure that the code is maintainable, that developers stay up to date with technology, and prevents the formation of knowledge silos so that you don’t end up with some magic code which only one person can understand. It’s more about company culture than technology.

What? #

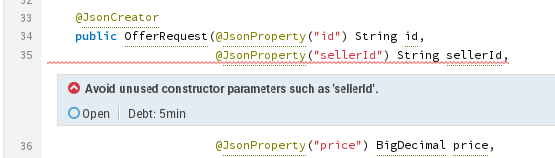

Note that I used the term software quality, not code quality. It’s nice if your code reviews allow you to fix formatting errors or minor code smells but there are also automated tools such as Sonar or IDE plugins which are quite good at that. A much more important part is finding deficiencies in the architecture or outright logical errors. This matters especially for issues which are hard to find during testing (whether automated or manual), for example those related to:

- security

- concurrency

- handling of rare errors

- configuration (usually different in testing than in production)

Some kinds of requirements can in theory be tested well, but in practice this is sometimes hard to achieve and issues may slip past testing:

- user interface

- validations

- performance

- integration with external systems

Another very important subject to pay attention to during reviews is:

- automated tests

Recently, a colleague found a rather serious error in my code during a review. The code in question was a scheduler which was supposed to perform a certain action at trigger time and to enqueue another action for later execution. Tests which I had written contained a flaw which caused my error to go undetected even though I thought I was testing that specific scenario. Having a code review allowed the error — both in the algorithm and in its tests — to be found and fixed even before it reached testing phase.

Tests deserve special attention because they are usually themselves not subject to testing. Careful code review can make up for that. There are tools for test verification such as mutation testing, but they only find the tip of the iceberg. Test coverage tools may be helpful but coverage is just a very simple metric and it is quite possible to have high test coverage and yet the tests to be of little value. Such tools are also often slow and since they do not really understand what a test is supposed to do (and what the tested software is supposed to do), their application is limited. When reviewing tests, pay attention to what the tests actually check, whether their names are true to their actual content, and whether they won’t make your development harder in the future, for example due to overmocking.

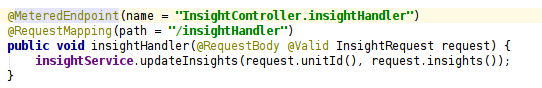

Also, look out for missing tests: if a functionality or requirement is not covered by automated tests, it may accidentally disappear at some point when you refactor your code and you won’t even notice. Especially fragile are features added via annotations or AOP, such as error-handling, retries, request validation, authentication etc. You may think that adding an annotation adds some piece of functionality but in practice invalid Spring setup or conflicting aspects can render it inactive. So, such functionality requires tests, and code reviewers should check if these tests are present.

Using code reviews to spread knowledge in the team is crucial if you want to treat collective code ownership seriously. Reviewing code written by others allows all team members to be able to take on work in any part of the project and to be aware of any recent changes.

Another benefit is learning not only about what’s going on in the project but also learning new technologies as well as proper use of the ones you already know. Reviewing code which uses a new library can be a great introduction before you start using it yourself. For example, I have learned a number of neat language idioms and useful expressions when reviewing Kotlin code written by others before I started using Kotlin myself.

Discussions which arise during reviews allow the team to arrive at common standards and to learn the pros and cons of different approaches to solving the same problem. This is very useful while a new team is forming: if you see a particular issue come up in code reviews more than a few times and not everybody agrees, it’s an indicator that this issue should be discussed with the team and perhaps the preferred solution you come up with together should be added to your coding standard.

How? #

Use a tool #

There are several approaches to code reviews. In my experience, very informal over-the-shoulder reviews do not work on their own. They can be helpful as a way of discussing a single problem, e.g. asking a colleague “which of these two options do you think is better?” but they are not good enough for checking a whole day’s work or more. There are two reasons for this. First, without using a diff tool it is not possible to see all changes clearly. Second, if the author is showing their code to the reviewer, they are introducing some bias, e.g. skipping over parts of code which they think are trivial while in reality they may contain errors. There is also usually not enough time to think thoroughly about each piece of code when reviewing it together with another person.

So, a dedicated code review tool such as Gerrit, GitHub or Bitbucket (aka Stash) is a must. They all integrate well with git, and while we’re at it, you can really benefit from learning to use git and git flow well. You can simplify the flow as you see fit, but the basic premise of using separate branches for all new tasks and merging them to main branch via pull requests is really useful. Some people are still using git as if it were SVN and that’s a shame. Do not be afraid of branching and merging since git is really good at these things, and they make working on a team without getting into other people’s way much simpler.

Organize the review #

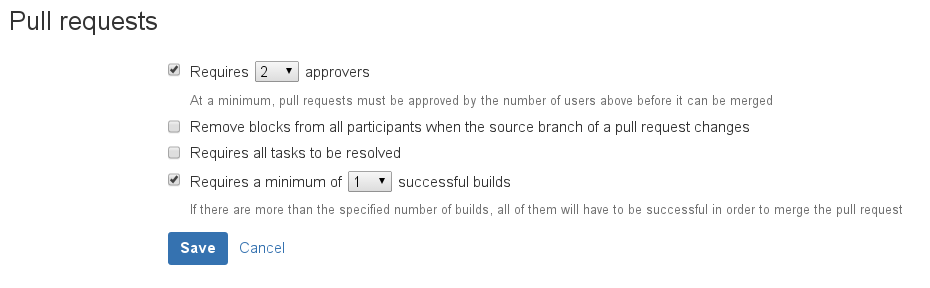

Different teams use slightly different code review rules, so I’ll describe what the team I’m currently on uses. Each new task is implemented on a separate branch and a pull request (PR) is created in Bitbucket. A PR requires approvals from two people who have not worked on it before it can be merged and the code passed on to testing stage.

The number two seems optimal. One is too little since each person has a different point of view and a single person may not be able to spot all issues. Above two, the amount of work increases, but there seems to be little extra profit. If some controversy arises, you can always ask yet another person for their opinion. Note that code developed using pair programming is usually of better quality than code written by a single person, so it may be OK to review such code by just one person who wasn’t in the pair, though two is still better than one.

Some teams just assign all their members to each code review and hope that at least two will find time to review the code quickly. If they don’t, the task may become blocked from further progress. A different approach, which I have seen to work quite well, is the author asking two specific people who would agree to review the code. This means that these two people can start working right away and are fully focused on the review. When a whole bunch of people are added to a review, there is the risk of them waiting for others to review the code first, or not being very focused. This does not always have to happen, but blurred responsibility may reduce the review’s effectiveness.

One observation that I have confirmed time and again is: the smaller the pull request, the higher the chance of a good code review. If the PR modifies 50 files, then after seeing the first 20 reviewers become numb and tired. In such state they are very likely to miss something important. So, as much as possible, try to make pull requests small. If you perform a large refactoring before implementing a change, try to extract it into a separate pull request. It’s easier to first review one PR with changes such as renaming a class or moving classes between packages and then another one which adds a feature than one huge blob which contains both kinds of changes.

Be civil #

The goal of a review is to create better code, so it is in the author’s best interest to have the code analyzed and commented on. Any issues found at this stage are issues saved from testing and production, meaning less work and less embarrassment for everyone. I have had my code sometimes subjected to very strong criticism and I think it was very beneficial: the final version was much better than the original and I learned a lot in the process. So, code reviews should be honest and strict but with the goal of producing better software, not of making the author feel stupid. The author should not feel bad about their code being criticized, while reviewers should take care to comment on code rather than to attack the author.

In order to facilitate this, comments should always be constructive. Don’t say bad variable name, suggest a specific better name. Instead of criticizing the architecture in general, say what changes should be implemented. Once in a while you may have a feeling that something is not right but not have a specific idea of how to improve it. In this case you may add a vague comment, perhaps as an invitation for other reviewers to take a closer look and think about possible improvements in the indicated area, but this should be a rare exception from the rule.

Unless proven otherwise, I assume people who work with me are responsible individuals. With this assumption, one can treat code reviews as a means of discussion rather than of control. Review comments are input which the receiver should take into account but they may as well decide that some reasons speak against implementing the change. So unless there is some really obvious bug in the code (which happens rarely), comments are just that: suggestions, not commands to do things another way. Sometimes, especially when it comes down to taste, an author may even receive contradictory comments from two different reviewers. Again, it is up to them to decide what to do with this input. Of course, if a reviewer believes their suggestion is really crucial, they may insist on implementing the change and a face to face discussion is needed in order to resolve the difference of opinions.

Pick your battles: there are some issues which may really break an application, but many things found in code reviews are about choosing a slightly better option over another or about different ways of doing things which do not matter that much and are easy to change later on. Comment and make your suggestions known but don’t get into long and exhausting discussions about minor details.

Do not be overly formal #

While I said completely informal reviews were not enough, they can still be very helpful. If you notice some place in code is attracting lots of comments and comments replying to previous comments, it may be time to put the formal tool aside and ask participants to just talk face to face. Some issues are easier explained by talking and handwaving than in writing. Also, discussions in writing are more likely to escalate into off-topic flames or personal attacks than when people meet in person. You may also ask extra people to join the discussion in order for everyone to arrive at a common conclusion.

Who? #

Since reviews are a kind of discussion rather than a tool of control, everyone should be allowed to review everyone else’s code. Seniority doesn’t matter: a junior developer can learn a lot by reviewing his senior colleague’s code and since everyone makes mistakes, a senior developer may have made a mistake which the junior may be able to spot. Of course, it is still a rather good idea to have code written by inexperienced developers reviewed by their senior peers, too. Likewise, if there’s some really critical code to be reviewed, let at least one of the reviewers be someone very experienced in that particular area, but let others look at it too.

I think it’s important to have the review done by a diverse group. People tend to have their hobbyhorses: one developer might be very particular about keeping the domain model clean, another might care about naming things and yet another may have a good eye for spotting missing test cases. Each of them can provide you with a unique insight. You can also invite people from other teams who are known for their experience in a particular subject area to review code which is especially important or which uses libraries or language features your team is not so experienced working with.

If you go through our recruitment process, we will probably among other things ask you to review some code, too. Seeing how a person reads others’ code and what kind of issues they can spot tells you a lot about their experience and their approach to software development. It’s really interesting that you can present the same piece of code to a junior fresh out of school and to a developer with ten years of experience and they will both be able to spot some issues. But it’s the type of issues they spot that show how deeply each of them can understand the code and the changes they suggest are what shows how well versed they are with architecture and design.

Going through changes #

Just like depending on experience, people spot different issues with the same piece of code, likewise teams learn to conduct better and better code reviews over time. When we started regular code reviews at Allegro, they often boiled down to minor issues such as code formatting, renaming variables and maybe extracting some code to a separate method here and there. We dubbed this stage Sonar-Driven Development since most code reviews were about things which could be found by Sonar as well. Fortunately, with time we started paying attention to higher-level issues such as good design, separating business logic from the persistence layer or making sure the code was understandable and maintainable.

Architecture and design are things which automated tools can’t take care of as well as of basic coding conventions but which in the long run are much more important than minor details. Of course, sticking to coding conventions is important, but fixes such as renaming a class take about 15 seconds thanks to our IDE’s refactoring functions, so you can easily fix the name any time. But if you choose a bad architecture or if you mix different layers in the application, it may become cumbersome to develop and maintain which is much harder to fix later on.

Discussing these higher-level properties of your code is the main source of increased quality and hopefully even if right now your reviews boil down to only discussing basic coding conventions, gradually they can lead to much more serious improvements. They also encourage sharing knowledge and helping peers. For me personally this is one of the factors which make working on a team fun. Even though code reviews are a big time investment, I believe that if done right they can greatly improve the quality of your software and make it easier to maintain in the future.