How we saved over 60% of k8s resources in our frontend platform

In this article, we want to share our journey of searching for optimizations in one of Allegro’s main microservices: opbox-web. You’ll read about the issues we had to deal with and how we managed to overcome them — together with a few surprises along the way and even one golden rule broken.

What is the opbox-web service and why is it important for Allegro? #

This service handles rendering of pages configured in Opbox page manager for both web browsers and native apps (MBox).

Being at the front of Allegro ecosystem, it receives a lot of traffic.

Its job is to take the page structure and data received from opbox-core and render the final output before it’s sent to the client.

Finally, it is THE service which executes the code of all components written by our product teams in our microfrotends ecosystem — Opbox (almost 900 at the time of writing).

Issues we wanted to tackle #

-

Low throughput: ~10 RPS per instance

-

Frequent timeout errors from FaaS components — our internal serverless feature

-

High total number of k8s instances

-

Issues with our service mesh (Envoy) on deployment — increased synchronization times

-

High resource allocation:

- a couple thousand CPU cores (app + Envoy sidecar)

- a few TB of allocated memory (app + Envoy sidecar)

-

Unreliable components’ execution time metrics, caused by incorrect scheduling of tasks in the NodeJS event loop

-

Complicated internal application architecture

- Support for FaaS components with separate rendering logic that had to be synchronized with the rendering logic of embedded components

- 3 levels of process, using different Node APIs (note the process names for further reading):

- 1

MainNode process, launched directly in the container - 3 cluster mode subprocesses (

Workers) handling incoming connections - 6 worker threads subprocesses (

Renderers) handling actual rendering (eachWorkerspawned 2Renderers)

- 1

How did we get there? A little history lesson #

- We decided to write

opbox-webusing theNodeJSruntime environment to lower the entry threshold for new developers, and to minimize the effort required to migrate existing frontend applications to our stack - When the ecosystem of components steadily grew, some of them rendered a very large part of the user interface, which took a lot of time and thus negatively impacted the throughput of application instances. With Opbox taking over more allegro.pl traffic, it required more hardware resources to handle the increased number of requests.

- We had to develop a solution that would increase throughput of a single application instance, in order to handle increased traffic. That’s how worker-nodes library came to be.

- The ecosystem of components grew and application needed more and more memory. Because of the way that max heap size is defined between Worker process and Renderer processes, we had to increase allocated memory way more than we actually were able to use (Worker process must have at least the same amount of memory allocated as the Renderer processes).

opbox-webeventually became the proxy toopbox-core, for all backend requests from MBox views in our native apps. This change allowed developers to implement MBox versions of their Opbox components by using mbox.js library instead of writing them directly in MBox service, in Kotlin language. This, along with migrating Offer page from native view to MBox, significantly changed the characteristic of traffic thatopbox-webhandled, because of the increased number of JSON responses in comparison to HTML responses.

The journey #

TLDR: #

- We deprecated FaaS components and removed all related code from

opbox-web - We separated component rendering into macro tasks. This prevents one component from skewing other component’s measurements and improves event loop efficiency

- We increased throughput, which allowed us to reduce the number of instances

- We simplified service’s architecture by baking Renderers directly into Workers

The FaaS deprecation #

FaaS was our internal serverless feature. It was introduced as a way to independently deploy Opbox components in April 2023.

Components deployed using FaaS were rendered on-demand via HTTP request, instead of being loaded from memory of opbox-web instances.

This allowed teams not to worry about the deployment schedule of regular Opbox components.

Unfortunately, because of its distributed nature, this solution was only available to a narrow group of components.

The performance impact of network overhead was too significant to allow rendering smaller, more frequently used ones.

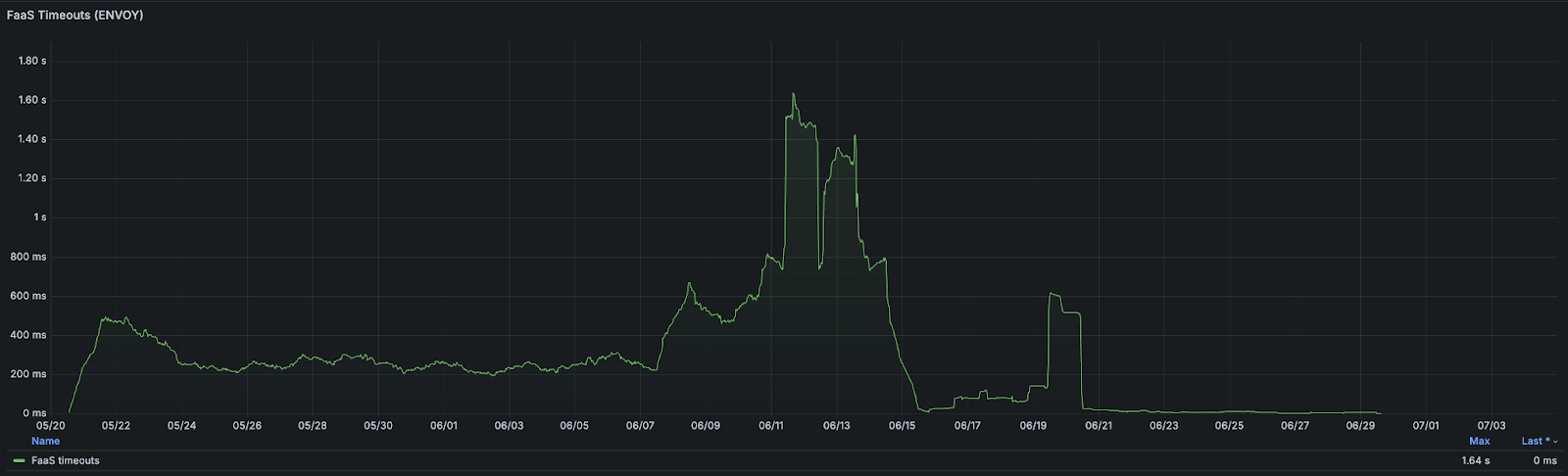

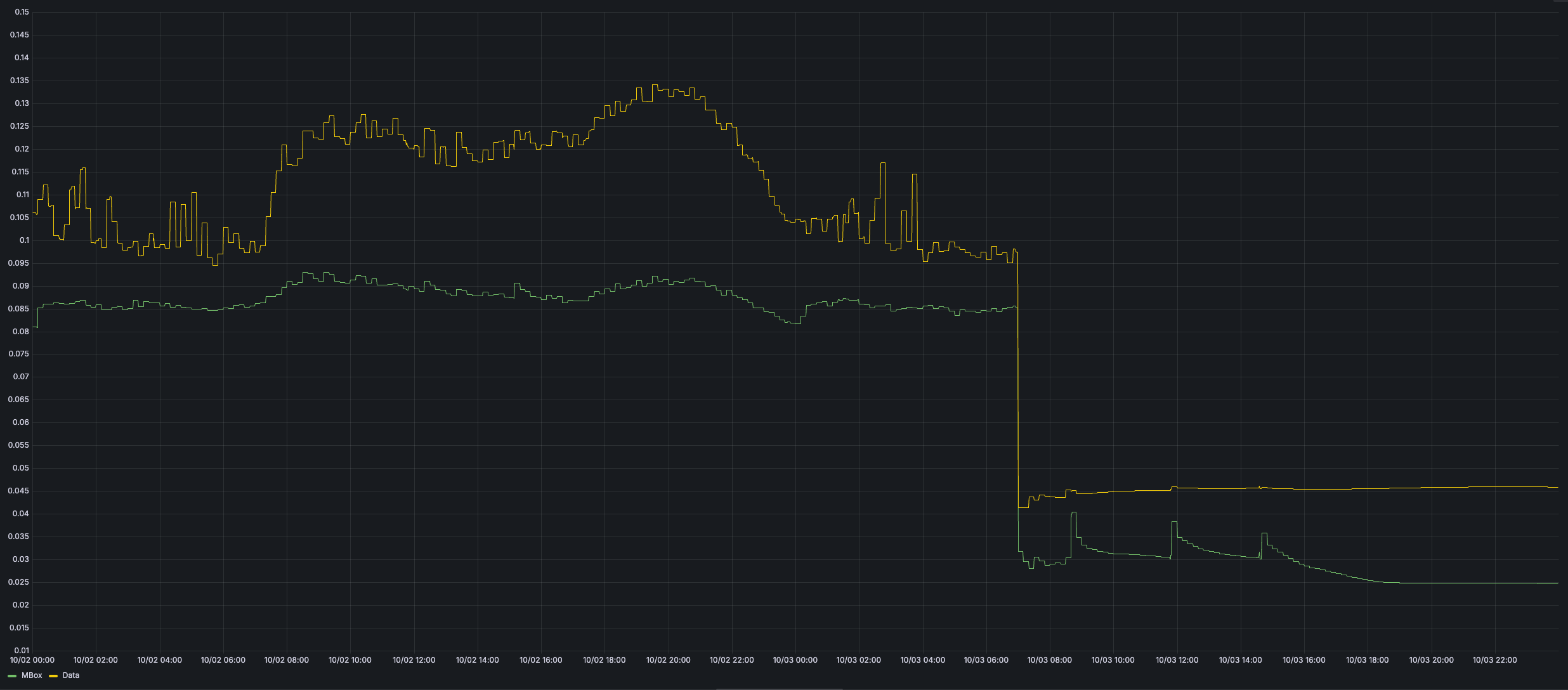

Almost a year after its introduction, FaaS components’ end of life was announced. It turned out the negative overhead of rendering components remotely was significantly impacting both our performance metrics and our users. Below you can see a chart with the number of times when remote components did not manage to return a response within the 300 ms limit. Each of these timeouts meant a user did not see some part of the visited page.

All FaaS components were migrated back to regular components by the end of Q2 2024.

The architectural changes #

Single process #

As mentioned above, we had 2 levels of subprocess: Workers and Renderers.

Workers were responsible for:

- accepting incoming connections

- fetching page structure and data from

opbox-core - passing it to one of their Renderers via inter-process communication (

IPC)

The chosen Renderer was then responsible for:

- selecting correct component implementation of all the boxes found on a given page

- rendering the components

- calling

css-bundlerservice to obtain final CSS assets to attach to the HTML output - preparing the render output and passing it back to the Worker, again via

IPC

Finally, Worker converted that render output into the final response and sent it back to the client.

We had a suspicion that sending those big JSON objects via IPC was hurting our performance. To test it out, we changed the internal architecture of our service to run on a single process: Main + Worker + Renderer — all packed together into a single Node executable. After benchmarking it locally, on a special test environment, and holding the new architecture on the canary environment for an hour, we knew we were onto something.

The single process approach had one more potential benefit.

In the old architecture, usage of Node’s worker-threads API (via worker-nodes library) to spawn the Renderers didn’t allow us to configure reasonable memory limits for Workers.

Why? It turns out that if a process that spawns a worker thread has a memory limit set, it’s not possible to set a different limit for the worker thread.

And Renderers needed much more memory than Workers.

So we had to declare more memory for Workers than we actually needed just to satisfy the Renderers’ requirements.

Having Renderers and Workers together in one process would allow us to better manage the memory allocation.

Resource allocation #

That’s when we encountered our first major problem: the new architecture required significantly less hardware per k8s instance, but at the same time we would need to deploy more instances.

How many? We ran the numbers and it turned out that to handle the production traffic we would need 2.5× more containers.

This was simply too much for our infrastructure to handle, especially on the Envoy side.

That’s how we learned that Envoy already had problems with synchronization when a new opbox-web version was being deployed.

Increasing the number of instances (although each would be much smaller) was off the table.

During these infrastructural discussions we noticed one more important fact: opbox-web was configured to reserve 3 CPU cores per instance, while spawning 10 Node processes: Main + 3 Workers, each with 2 Renderers.

This effectively never allowed our application to reach its full potential before the autoscaler kicked in to spawn more instances.

This observation prompted us to increase our CPU allocation to 7 cores.

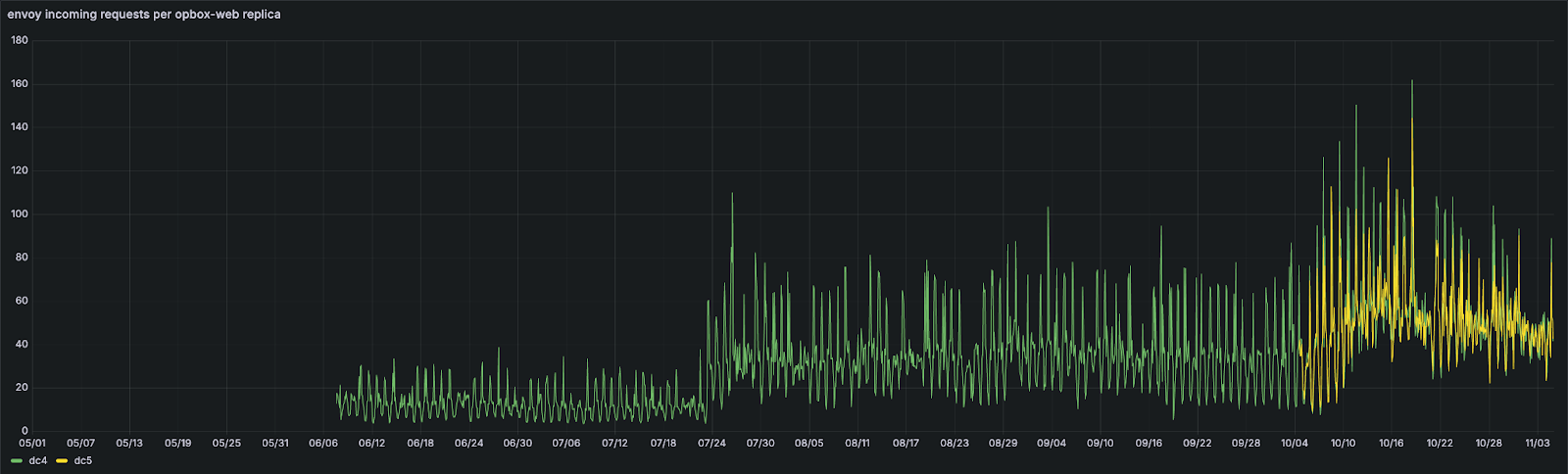

This change was deployed in the morning of 23.07.2024.

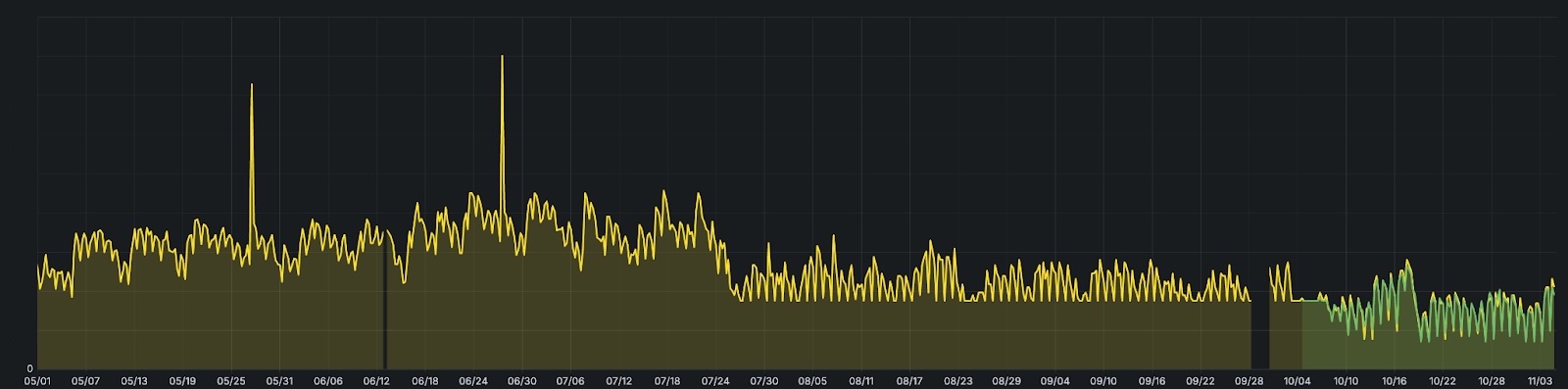

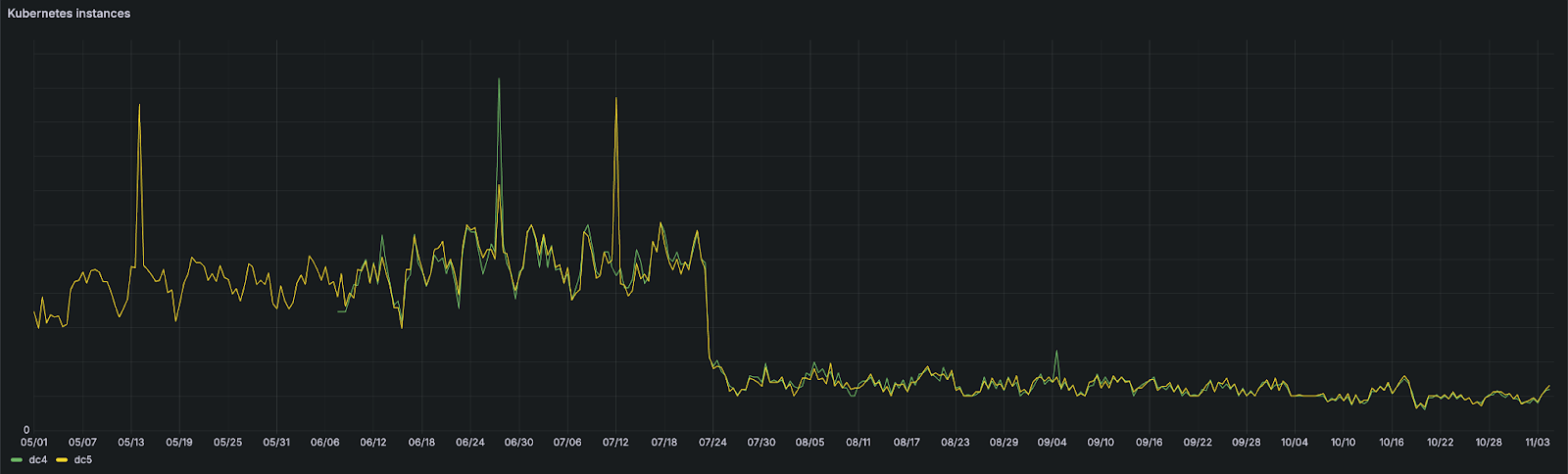

And just like that, RPS per instance tripled, and the number of instances dropped to 27% of the previous amount.

This in turn halved the app’s CPU and memory allocation.

Many instances in one? #

But we weren’t done. The single process approach hadn’t been deployed yet.

We knew it had potential but at the same time we couldn’t run as many instances as it required, so we needed to find a way to reduce their number.

How could we do that? Just run multiple instances of the single-process version of opbox-web inside one container 🙂

To do this, we reached for an industry-standard library for such cases: pm2, but soon realized it comes with a big drawback: the AGPL 3.0 license.

It forces all software using this library to be open-sourced, which for obvious reasons we just couldn’t do.

After searching and failing to find an alternative, we had to go back to the drawing board.

What else could we do?

The answer turned out to lay in the existing opbox-web architecture: run the single process app in Node.js cluster mode.

After all, that’s what pm2 does under the hood as well.

This approach would add some complexity compared to the 100% single process approach, but would also allow us to have more control over the cluster and better monitor the Main process.

We decided to go with this approach, and implementing it turned out to be quite trivial: most of the code was already there.

The CSS Bundler timeouts #

There was still one more obstacle left to overcome.

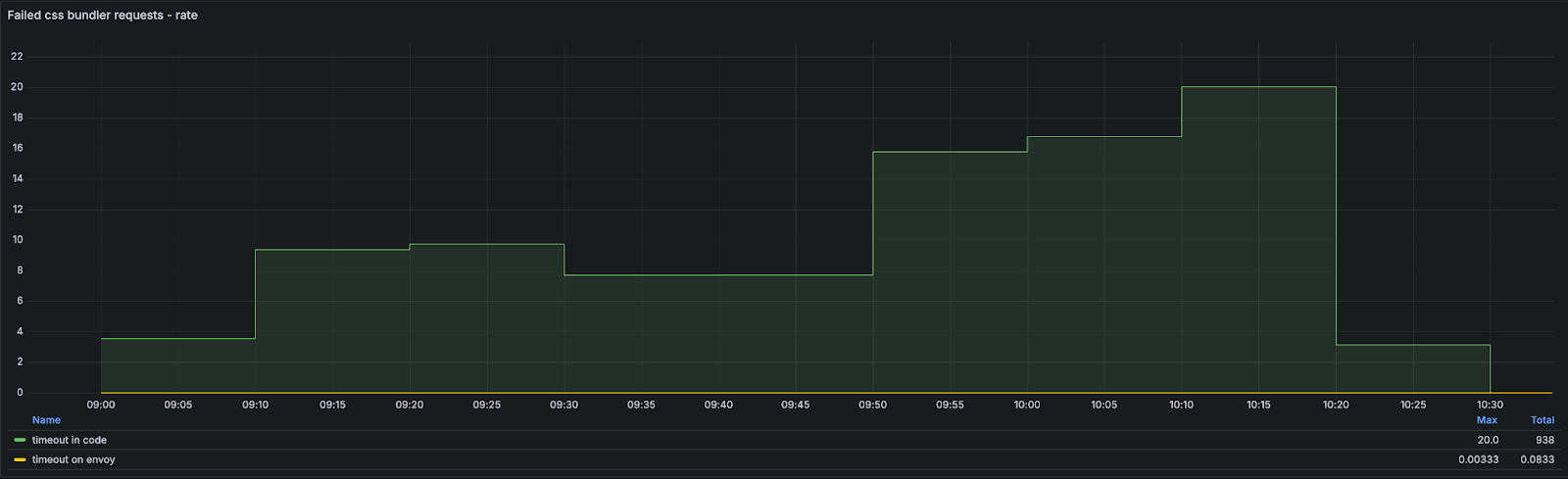

During our initial tests on the canary environment we noticed an increase in failed requests to css-bundler service.

These requests are made in opbox-web after the whole page has been rendered to combine CSS assets of all components present on the page into a single, cacheable asset.

It ensures that as long as the set of components on a given page doesn’t change, our visitors’ browsers won’t need to re-fetch these CSS assets.

We have a very small timeout (50ms) configured for these requests because we think it’s better to respond faster with unbundled assets than wait longer for the bundle.

After we took a close look at the increase in errors, we noticed that the css-bundler service responded well within the configured limit (~10ms), but our code was still throwing timeout errors.

How was that even possible?

That’s when it clicked for us: it’s the Node.js Event Loop! The old architecture limited Renderers to work on just 1 page at a time, so when the render was done and the Renderer called css-bundler, it wasn’t doing anything else besides waiting for the response.

With the new architecture, multiple pages could be rendered at the same time, so after dispatching the request to css-bundler, the Worker+Renderer combo just continued with its other tasks before the response was received.

This meant that sometimes, when it arrived, that other work prevented the Event Loop from handling the response before the configured timeout expired.

Fixing this issue forced us to dive deep into the event loop mechanisms to find a way to prioritize handling of css-bundler response versus other tasks.

At first we thought that separating each component’s rendering into macro tasks using setImmediate would be the solution.

We had it planned as a way to improve reliability of each component’s rendering time metrics anyway, so it seemed like a two-birds-one-stone situation.

It did help in fact, but didn’t eliminate the issue completely.

To fix it for good we had to go against one of the main rules of Node.js development:

Don’t block the Event Loop

With motivation to focus on fast response for a given page (as opposed to handling as many concurrent renders as possible), we found a way to wait synchronously for response from css-bundler.

The timeout errors were gone.

Single process deployed #

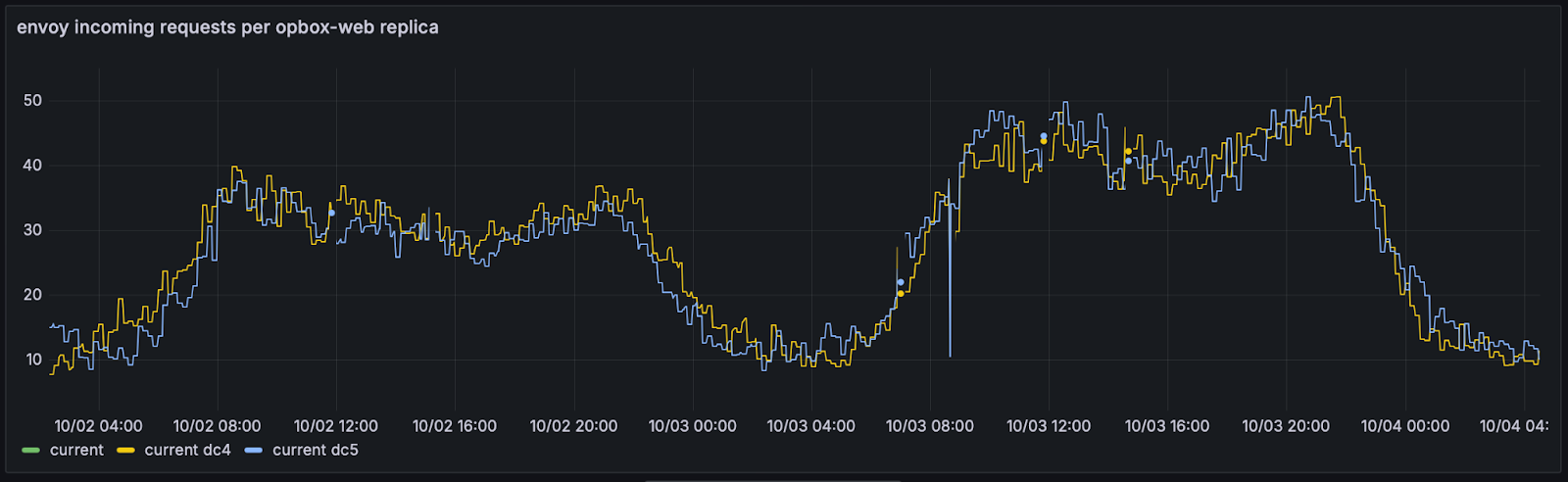

That last change allowed us to finally release the single process approach (not so single anymore, we now run 7 processes in each container: Main + 6 Workers — to reflect the old approach with 6 Renderers).

It was deployed in the early morning of 03.10.2024. Since then, opbox-web is able to receive ~50 RPS per instance, allowing us to handle production traffic with just ~10% of the original number of instances during the night and ~20% during the day.

Incoming requests per instance

JSON response render duration

The final results #

FaaS errors are gone. Migrating away from remote components allowed us to simplify the rendering logic that laid the groundwork for later changes.

We also got a confirmation from the service mesh team that they no longer observe spikes in synchronization during opbox-web deployment.

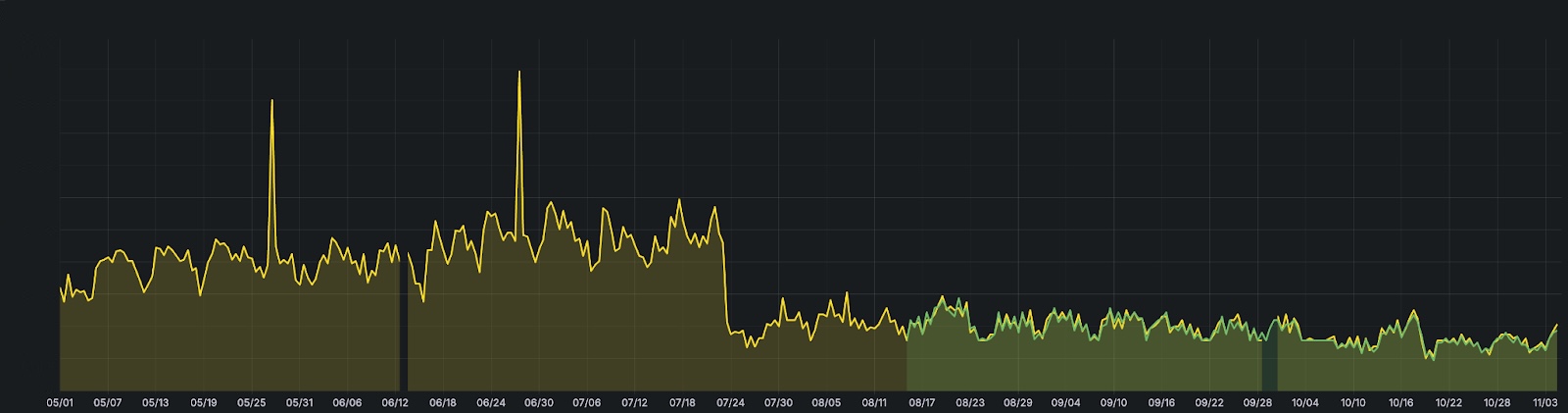

Over this long journey, opbox-web evolved from a high number of daytime instances, each requesting 3 CPU and 10.24 GiB of memory (4 CPU and 11.24 GiB with Envoy sidecars) to 80% less daytime instances with 7 CPU and 16.384 GiB of memory (7.3 CPU and 16.896 GiB with sidecars).

In the end, we calculated a whopping savings of ~64% of CPU cores and ~70% of memory.

Memory usage per DC

CPU requests per DC

K8S instances per DC

RPS per instance per DC