MBox: server-driven UI for mobile apps

In this article, we want to share our approach to using server-driven UI in native mobile apps. In 2019 we created the first version of the in-house server-driven rendering tool called MBox and used it to render the homepage in the Allegro app on Android and iOS. We have come a long way since then, and now we use this tool to render more and more screens in the Allegro app.

After over three years of working on MBox, we want to share how it works and the key advantages and challenges of using this approach.

Why server-driven UI? #

The idea behind MBox was to make mobile development faster without compromising the app quality. Implementing a feature twice for Android and iOS takes a lot of time and requires two people with unique skill sets (knowledge of Android and iOS frameworks). There is also the risk that both apps will not behave consistently because each person may interpret the requirements slightly differently.

Using a server-driven UI solves that problem because each business feature is implemented only once on the backend. That gives us consistency out of the box and shortens the time needed to implement the feature. Also, developers don’t need to know mobile frameworks to develop for mobile anymore.

Another advantage of server-driven UI is that it allows releasing features independently of the release train. We can deploy changes multiple times a day and when something goes wrong — roll back to the previous version immediately. It gives teams a lot more flexibility and allows them to experiment and iterate much faster. What’s more, deployed changes are visible to all clients, no matter which app version they use.

How does MBox work? #

Defining the screen layout #

While designing MBox, we wanted to create a tool that would give developers total flexibility to implement any layout they need — as long as it’s consistent with our design system, Metrum.

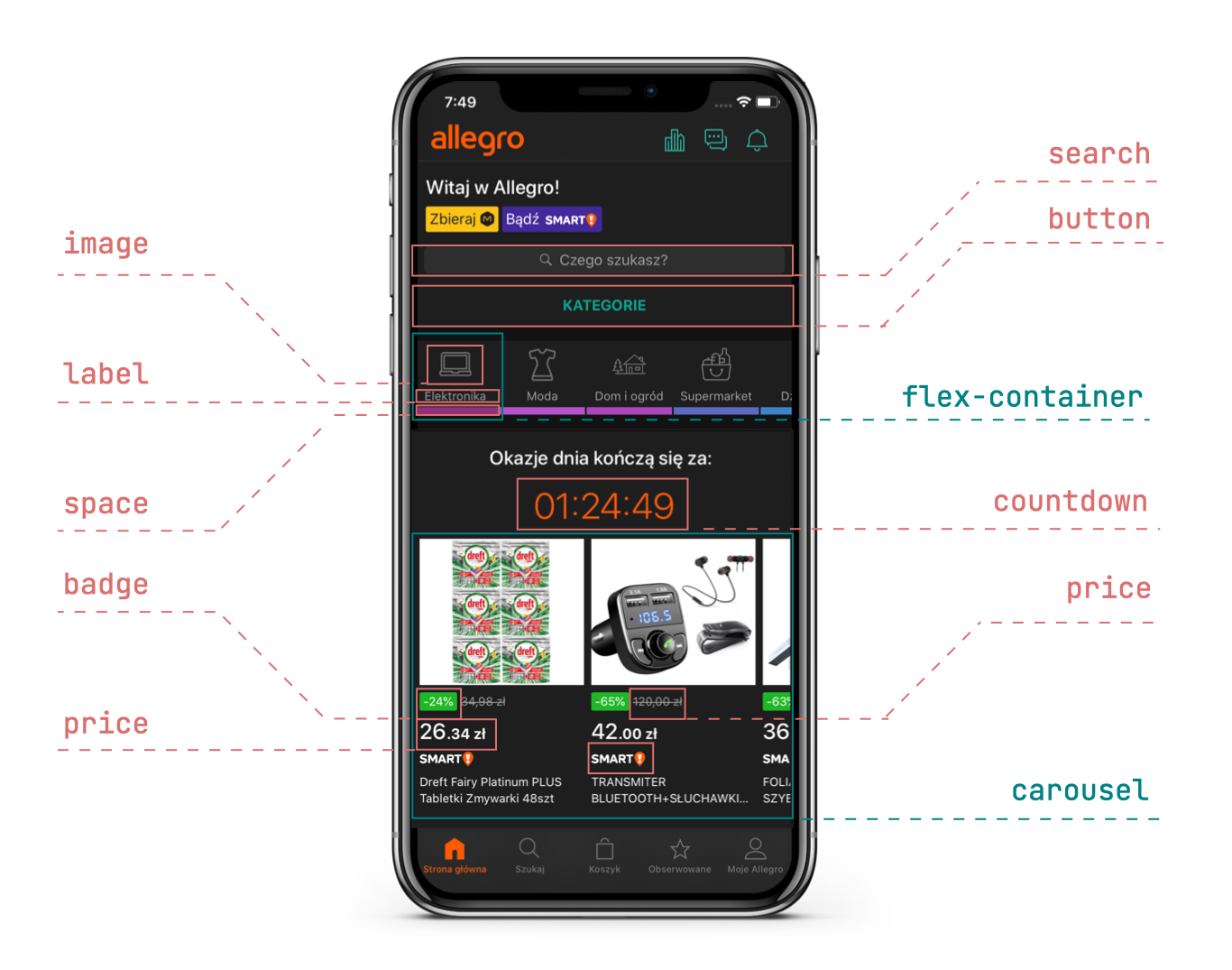

That’s why MBox screens are built using primitive components, which our rendering libraries map to native views.

Developers can arrange MBox components freely using different types of containers that MBox supports (flex-container,

stack-container, absolute-container, list-container, etc.). Those components can be styled and configured to match

different business scenarios.

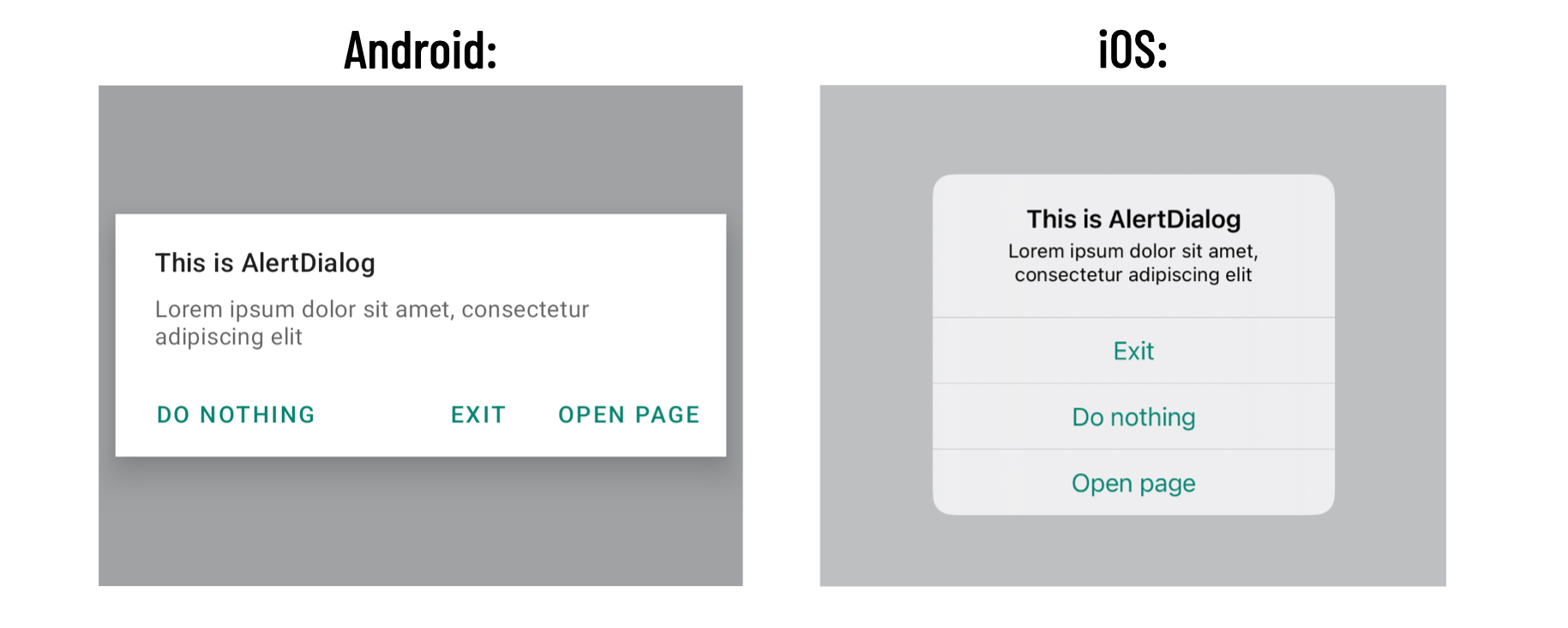

MBox renders components on mobile apps consistently, but it also respects slight differences unique to Android and iOS platforms. For example, dialog action in MBox supports the same functionalities on both platforms, but the dialog itself looks different on Android and iOS:

That gives MBox screens a native look and feel and perfectly blends in with parts of the app developed natively, without MBox. We had to add a label that shows which parts of the app are rendered by MBox, because even mobile developers couldn’t tell where native screens ended and MBox started.

What about more complex views? #

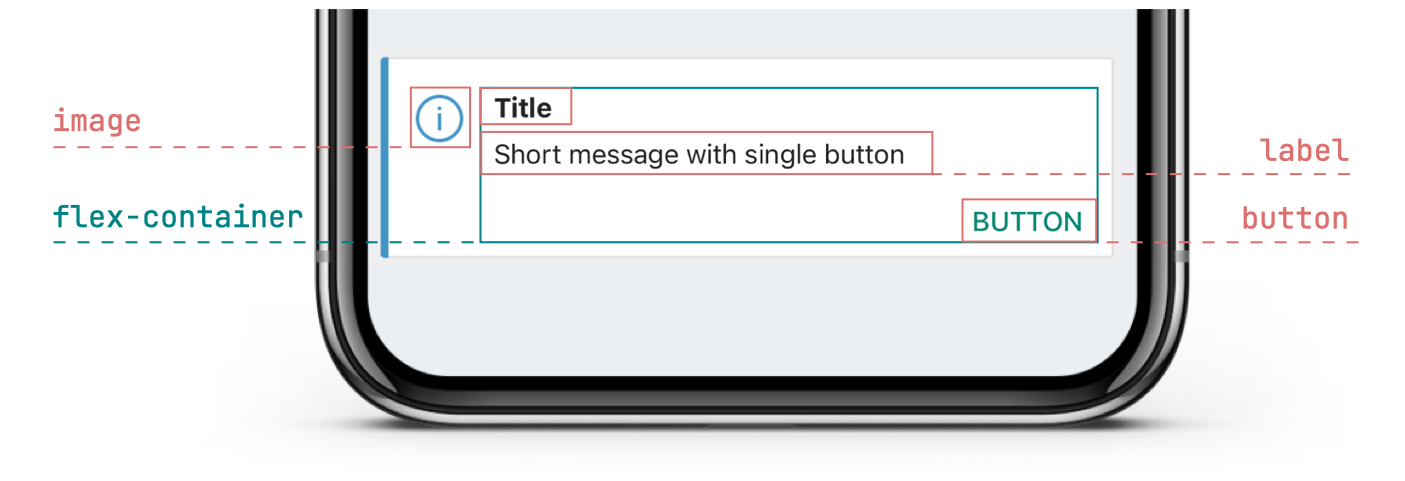

Creating more complex, reusable views is also possible. For example, our design system specifies something called the message: an element with a vertical line, an icon, and some texts and buttons. However, because this element is complex and its requirements may change over time, it’s defined on the backend service as a widget — the element that developers can reuse across different screens.

If the requirements for the message widget change, we can easily modify it on the backend side without the need to release the app. That’s because it’s not defined directly in the MBox libraries included in the mobile apps, but specified on the backend using MBox components.

Unified tracking #

Besides defining layouts, MBox also allows us to specify tracking events on the backend. For tracking events, consistency is crucial. If events are not triggered under the same scenarios and with the same data on both platforms, it’s hard to compare the data and make business decisions.

MBox solves that problem. All events tracked on MBox screens are defined on the backend, meaning unified tracking between Android and iOS and across different app versions.

Testing #

Since the MBox rendering engine is a core of more and more screens in the app, it had to be thoroughly covered by unit tests and integration tests. We also have screenshot tests that ensure that MBox components render correctly. That allows us to find out early about possible regressions.

Teams that develop screens using MBox also have various tools that allow them to test their features. They can write unit tests in the MBox backend service and check if correct MBox components are created for the given data. They can also add a URL of their page to Visual Regression — the tool that creates a screenshot of the page whenever someone commits anything to the MBox backend and if any change in the page is detected, the author is automatically notified in their pull request.

Feature teams can also write UI tests for the native apps to test how their page integrates with the rest of the app and if all interactions work as expected. However, those tests have to be written on both platforms by the mobile developers and should take into account that the content of the page under tests can be changed on the backend.

The journey to make MBox interactive #

When we started working on MBox, we were focused mainly on pages that contain a lot of frequently changing content but not many interactions with users. In the first version of MBox, it was possible to define only basic actions like opening a new screen or adding an offer to the cart. That changed gradually when new teams started using MBox.

To make MBox more interactive, we used the same atomic approach we adopted when designing MBox layout components. We gradually added generic actions that were not custom-made to serve specific business features but were reusable across different use cases.

For example: #

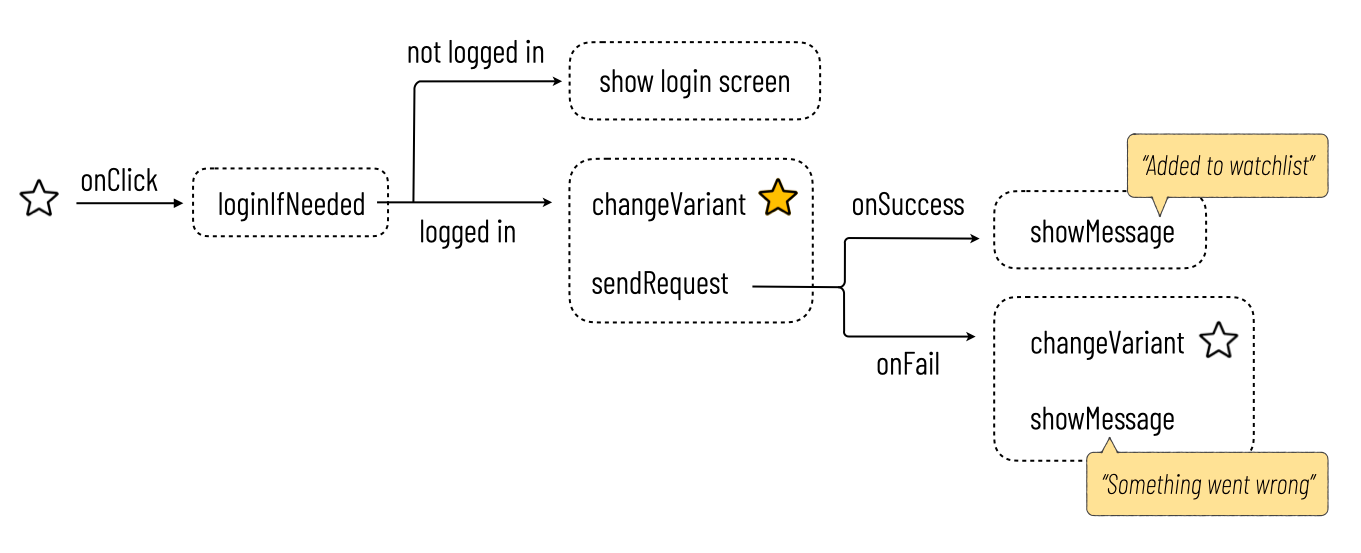

One of the first challenges that we faced was allowing the implementation of an “add to watchlist” star in MBox. We could’ve just added the ”watchlist star” component that checks if a user is logged in (redirects to the login page if it’s not), adds an offer to the watchlist, and changes the star icon from empty to full. In the short term, it should have been easier. But it’s not a way that would allow MBox to scale.

Instead, we designed a couple of atomic mechanisms that allow building this feature on the backend and could be reused in the future in different use cases.

We added a logic component called multivariant that allows changing one component into another thanks to the

changeVariant action. That enabled us to switch the star icon from empty to full. Next, we added the sendRequest

action

that sends requests with given URL, headers, and other data to our services. That allows adding and removing an offer to

and from the watchlist. Lastly, we added the loginIfNeeded action that allows checking if a user is logged in and

redirecting to the login screen if needed. That allows ensuring the user is logged in before making the request.

Of course, doing it this way took much more time than just implementing the ”add to watchlist” component in MBox libraries natively. But this is the way that scales and gives us flexibility.

Over time mechanisms that we designed earlier were reused on other screens. And more and more often, when the new team wanted to use MBox on their screen, most of the building blocks they needed were already there. It definitely wouldn’t be the case if not for our atomic approach.

The challenges #

We also encountered many challenges while working on MBox.

Consistency of the engines #

We create two separate rendering engines for mobile platforms, so we must be extra cautious to ensure everything works consistently. Even a tiny inconsistency in the behavior of the engines may be hugely problematic for the developers that use MBox. It may force them to, for example, define different layouts for each mobile platform.

To make sure the engines are consistent, each feature in MBox is implemented synchronously by a pair of developers (Android and iOS) who consult with each other regularly. During the work, they make sure that they interpret the requirements and cover edge cases in the same way. The new features are ready to merge only after thorough tests on both platforms that check both correctness and consistency.

Versioning #

On MBox, we also have to pay close attention to versioning. We use semantic versioning in the engines. Each new feature has to be marked with the same minor and major version on both platforms. We also prepare changelogs containing information about what functionalities are available in which version.

On the backend, we allow checking the version of the MBox engine that the user has and serve different content depending

on it.

For example, when the screen contains the switch component, supported since version 1.21,

we can define that for users who have the app with the older versions of MBox, checkbox will be displayed instead.

Testing changes introduced to the engines #

And last but not least: testing. Because MBox is used to render various screens in Allegro mobile apps, we must be cautious whenever we introduce engine changes to avoid negatively impacting existing MBox screens. The screenshot and UI tests cover every MBox component and action. We’re also encouraging feature teams to add their screens to the Visual Regression and cover their screens with UI tests in the mobile repositories. All those things allow us to minimize the risk of introducing a regression.

How does MBox connect to other parts of the Allegro ecosystem? #

Consistency across mobile platforms is not everything. Another important aspect of our work is making sure mobile and web platforms are as consistent as possible, respecting native differences that make each platform unique.

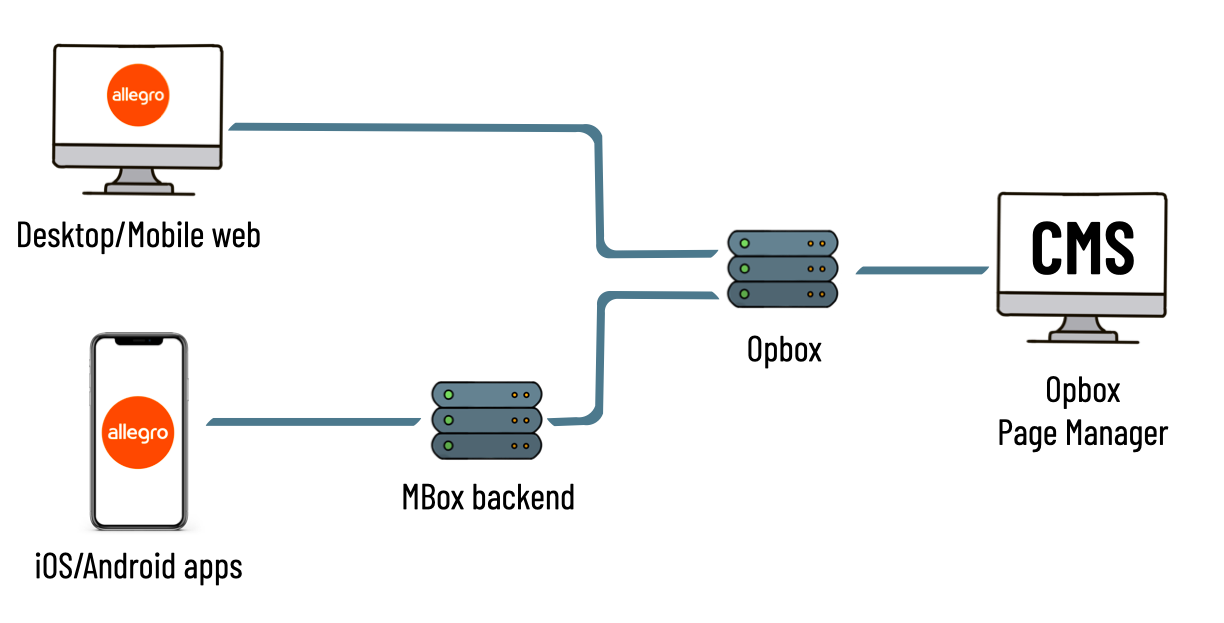

MBox integrates with our content management system, also used for the web (Opbox Page Manager). The screen’s content configured in the Opbox admin panel is sent through the Opbox services to the MBox backend service. The MBox service maps the data into MBox components that make up the MBox screen. Then the screen definition in JSON format is sent to apps and is rendered using native views.

The same data from Opbox is also used to render the web equivalent of the same screen. Opbox defines its own mappings for the web: Opbox Components, which describe how to map the data into HTML elements that make up the Allegro web pages.

Integration with Opbox gives us a lot of advantages. Very often, to change the content in the app and web, you don’t need to change the code at all — all you need to do is change the content in the Opbox admin panel.

Another huge advantage is that we have unified tracking between all platforms and can use the same tools for A/B testing that are used for the web. Previously, code for A/B tests had to be written for each mobile platform separately in native code and then cleaned up after the finished experiment. Now, some experiments work out of the box since Opbox sends different data to MBox depending on the experiment variant the user falls into. Sometimes a little bit of code in the MBox backend is required to conduct an experiment, but it’s not comparable to the amount of work A/B tests take when they’re performed in the native code without MBox.

Conclusions #

MBox is a tool that changed how we work on mobile apps in Allegro. It allowed us to shorten the development time without compromising the quality and stability of the app and without losing the native look and feel of the Allegro apps.

We have come a long way during those three years since we started working on MBox. At first, our ambition was to create a tool that would be used on content screens with very few interactions. Over time, we pushed the boundaries of what MBox is capable of and entered screens with more and more interactions with the user.

Currently MBox is used in over 25 screens in Allegro mobile apps and the number is still growing. In the first half of 2022 alone, 27 teams made changes to the app using MBox and created about 300 pull requests. We deployed changes over 100 times which means ~4.15 releases a week.

We’re confident that it’s not the end of the possibilities ahead of us. We still see how we can make MBox even more powerful. We’d love to shorten development time even more by providing tools that allow defining MBox screens in TypeScript. That’ll enable developers to reuse some parts of the code between mobile and web and take advantage of better tools such as hot reload. Another thing we’re currently focused on is adding the binding mechanism to MBox and the client-side logic to allow defining the business logic on the backend. Implementing those mechanisms will allow introducing even more interactivity into MBox screens.

But that is the topic for the next articles. Stay tuned!