Do repeat yourself! What is responsibility in code?

Did you know that in October this year, DRY principle will celebrate its 25th anniversary? It was proposed by Andrew Hunt and David Thomas in The Pragmatic Programmer book in 1999. 25th birthday is quite a good reason to celebrate, isn’t it? At least, it’s a good opportunity to bring this principle back into the spotlight and to discuss how to use it properly.

What’s the problem with DRY #

I’ve been a frontend software engineer for a slightly shorter period of time - around 8 years. From the very beginning of my career, I have known the DRY principle and have been using it. It probably protected me from many bad choices in coding.

But for most of my career, I had been using it wrong… And despite knowing it, I didn’t fully understand it.

I thought: If these two objects, functions or classes are similar, I have to do whatever it takes to merge them into one. Because I didn’t want to repeat myself. Maybe in simple cases, it’s a good approach, but in more complex situations, DRY is not enough.

What most of us think #

I believe most programmers’ understanding of the DRY principle is similar to mine from the past. And it’s about merging two of the same or similar elements into one.

Do you have two identical constants, objects, or functions doing the same thing? You should merge them to increase code maintainability.

However, the problem starts when two elements are not identical, but similar. Two similar objects? Ok, maybe you’ll think - let’s combine those sets of properties. Two similar functions? Ok, let’s merge and parametrize them. Unfortunately, it’s not always a good approach.

You also need Single Responsibility Principle to determine if you want to merge two elements in the code or not. What is the relation between repeating yourself and single responsibility? Let me show you an example.

Example #

Imagine you’re programming software for the coffee machine. The project manager gives you the requirements:

- the machine should make black or white coffee;

- user should be able to set the coffee size and strength.

Let’s start with this task. You could create a class called CoffeeMachine.

The first method takes coffee strength and size as arguments. It calls other methods to make coffee. The second method is pretty much the same but with the main difference - it pours milk at the end.

class CoffeeMachine {

constructor() {}

makeBlackCoffee(coffeeSize, coffeeStrength) {

this.takeBeans(coffeeStrength);

this.grindBeans();

this.pourWater(coffeeSize);

}

makeWhiteCoffee(coffeeSize, coffeeStrength) {

this.takeBeans(coffeeStrength);

this.grindBeans();

this.pourWater(coffeeSize);

this.pourMilk();

}

}

Another project #

Sometime later another project manager comes to you and announces you’ll create software for a similar device. It’ll be a cheaper machine, so coffee strength will be fixed without the possibility for a user to change it.

You start coding. You’d probably create a separate class and implement business requirements there. You need coffee strength as a property because a user can’t change it.

The method for making black coffee would take this value from the instance and coffee size from an argument. The other method would do the same.

class CoffeeMachineStatic {

constructor(private coffeeStrength) {}

makeBlackCoffee(coffeeSize) {

this.takeBeans(this.coffeeStrength);

this.grindBeans();

this.pourWater(coffeeSize);

}

makeWhiteCoffee(coffeeSize) {

this.takeBeans(this.coffeeStrength);

this.grindBeans();

this.pourWater(coffeeSize);

this.pourMilk();

}

}

At some point, you could notice that those classes are so similar, almost identical. You could think: “Hey I’ve seen this one before”. And then a thought comes to your mind: “Don’t repeat yourself!”.

You merge those classes, add a simple condition, and done! The nice, readable class serves two types of coffee machines.

class CoffeeMachine {

constructor(private coffeeStrength) {}

makeBlackCoffee(coffeeSize, coffeeStrength) {

this.takeBeans(coffeeStrength || this.coffeeStrength);

this.grindBeans();

this.pourWater(coffeeSize);

}

makeWhiteCoffee(coffeeSize, coffeeStrength) {

this.takeBeans(coffeeStrength || this.coffeeStrength);

this.grindBeans();

this.pourWater(coffeeSize);

this.pourMilk();

}

}

Negative consequences #

But what if there will be more requirements from both project managers in the future? For example: “We introduce Cappuccino in the first device”, or “Second device will be able only to make espresso, so there is no need for a user to choose the coffee size and it would not be able to make white coffee”.

Now look at your first nice and readable class. It would be not so readable and hard to maintain after a while. And it’s only a trivial, abstract, and naive example.

class CoffeeMachine {

constructor(

private coffeeStrength,

private coffeeSize,

private isMilkSupported,

private isCappuccinoSupported,

) {}

makeBlackCoffee(coffeeStrength, coffeeSize) {

this.takeBeans(coffeeStrength || this.coffeeStrength);

this.grindBeans();

this.pourWater(coffeeSize || this.coffeeSize);

}

makeWhiteCoffee(coffeeStrength, coffeeSize) {

if (this.isMilkSupported) {

this.takeBeans(coffeeStrength || this.coffeeStrength);

this.grindBeans();

this.pourWater(coffeeSize || this.coffeeSize);

this.pourMilk();

}

}

makeCappuccino(coffeeStrength, coffeeSize) {

if (this.isMilkSupported && this.isCappuccinoSupported) {

this.takeBeans(coffeeStrength || this.coffeeStrength);

this.grindBeans();

this.pourWater(coffeeSize || this.coffeeSize);

this.pourSteamedMilk();

}

}

};

What was the mistake here? You forgot about Single Responsibility Principle.

What is responsibility? #

Do you remember what SRP sounds like?

a class should have only one reason to change

I believe most programmers think this principle sounds more like: “a class/function should be responsible for one thing” or “should do only one thing”.

What is this reason to change? You can easily imagine actors from outside of the system. Those actors would come to you and demand some changes in your code. An actor could be a single person like a project manager, department, or some company.

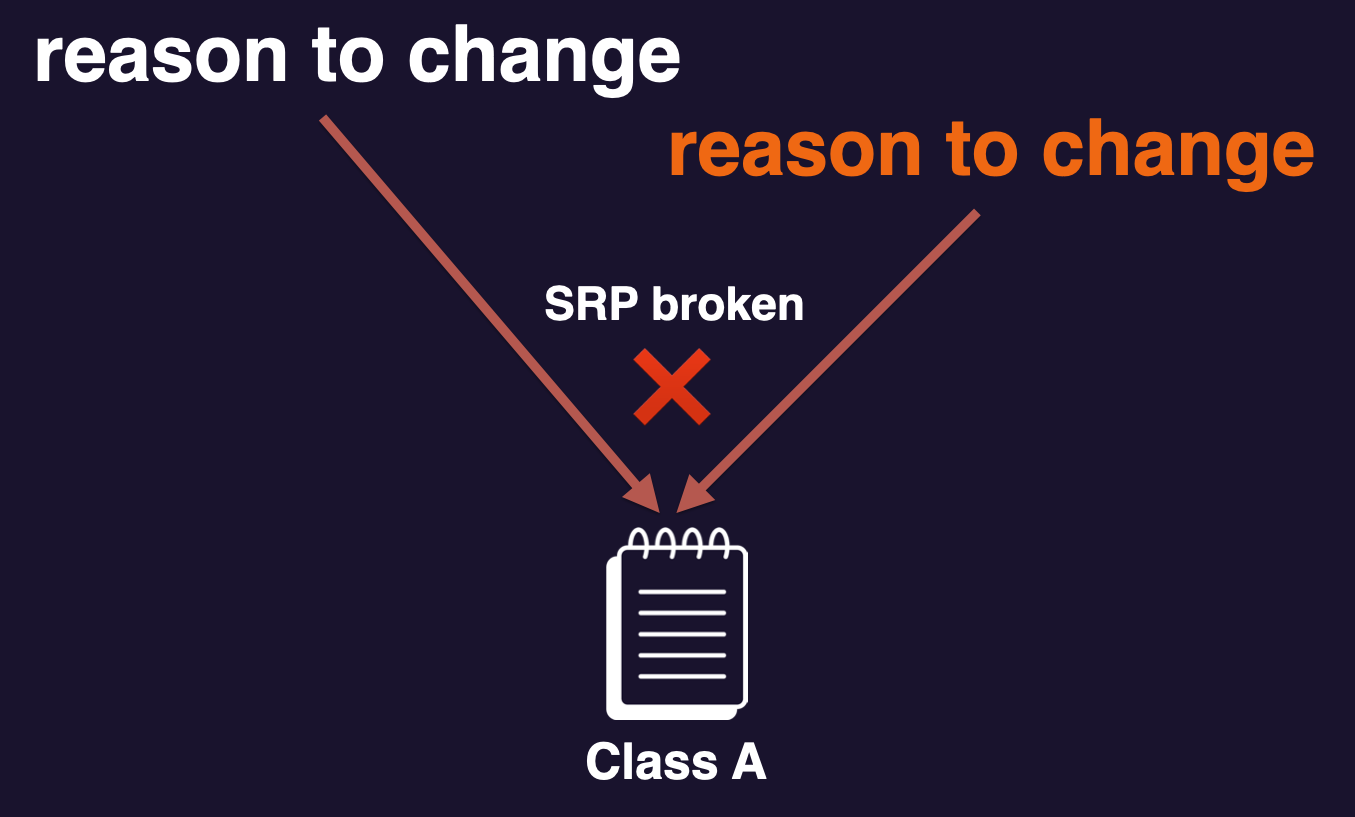

In our case of coffee machines, there are two project managers. They’re managing producing software for two at first similar but in fact different devices. So your final class handles two types of coffee machines. That means this class has two reasons to change. It means it has two responsibilities.

In most cases when the same class/function/module/service or component is used by multiple teams or departments, it has multiple responsibilities. You can imagine how hard it is to maintain a service when multiple people demand changes to this service. It’s almost impossible to satisfy all of them. The obvious exception is any kind of reusable stuff like libraries or generic components.

Allegro Archive example #

Let me show you a real-life example from my work at Allegro. Last year, as a tourist at the Traffic department, I was given the task of handling the listing component on the Allegro Archive site.

Note: Allegro Archive is a separate Allegro site for offers which are no longer available for sale. It works only for Polish Allegro for now.

A few years ago the team responsible for Allegro Archive used version 6 of the listing component that was used also on the Allegro site. Through the years listing component evolved. More features were added, and the API completely changed. But Archive didn’t need those changes, so they stuck to the 6th version.

After introducing health checks for frontend components, the listing team had their component marked as “Warning”, because of the outdated version 6 used on Allegro Archive.

Note: Health checks are key metrics that alert us about general tech debt such as outdated dependencies in our components and services.

Possible solutions #

We discussed a couple of solutions:

- Migrating to the newest version of the listing component.

- Forking and migrating to the newest Opbox libraries versions (to deal with health checks).

- Rewriting the whole component for the needs of the Allegro Archive.

Unfortunately, the first two solutions were really time-consuming and complex. Both the listing component and Opbox have changed a lot over the last few years.

The last one wasn’t my first thought, but ended up being the best solution. It was definitely the easiest and the least time-consuming solution. It also gave us the opportunity to prepare a component dedicated to Archive needs.

What was the mistake? #

Now, based on your correct understanding of SRP, what mistakes did we make in this situation?

There was one component used in different business cases. There were two reasons to change listing components - changing requirements for Allegro listing and Allegro Archive listing.

It wasn’t the worst case because Allegro Archive didn’t cause any changes for a few years, but finally, it came out that a bad architectural decision was made. In this case, the team responsible for Allegro Archive should have just duplicated the code.

What do you want to not repeat #

Ok, let’s go back to the DRY principle itself for a moment. I already mentioned it was introduced in the book The Pragmatic Programmer.

Now I have to confess something. Until I started preparing this content, I was unaware that this principle is not just “don’t repeat yourself”. It actually states:

Every piece of knowledge must have a single representation within a system

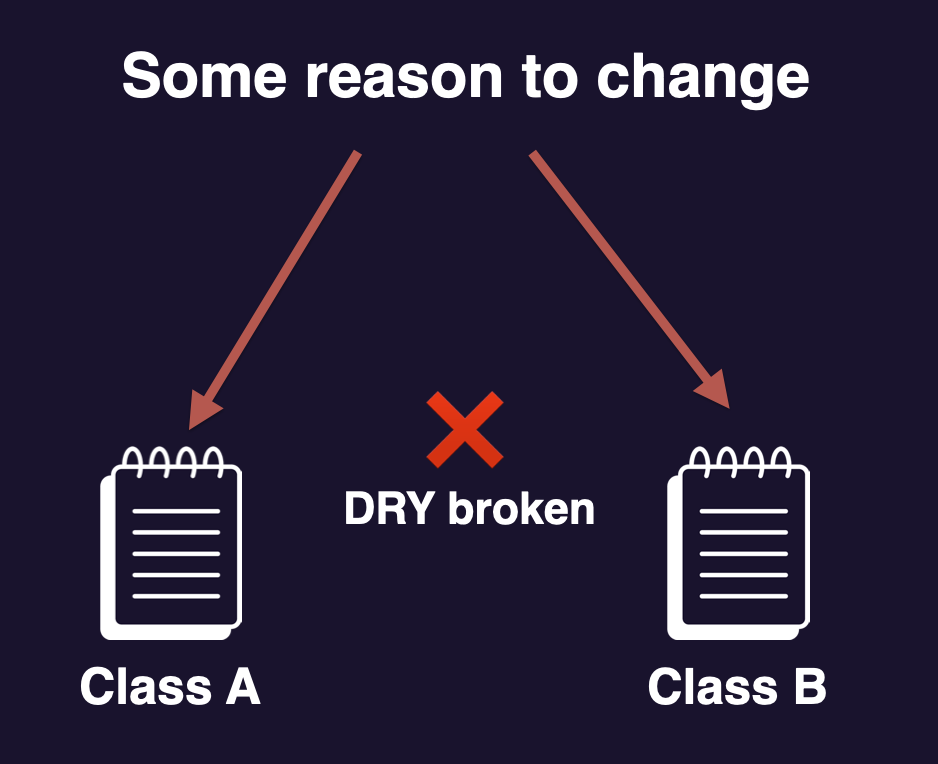

So it’s not only about two functions or classes doing the same thing. It’s about every situation when you change one piece of code, and then you have to change also another one because of that change. It’s inverted SRP. If you have two elements of code and only one reason to change for both of them, it means that the DRY principle is violated.

Summary #

I believe now you can see the very strong connection between SRP and the DRY principle. Let’s sum it up:

There always is a reason to change for an element of code. This reason is its responsibility. There should be a single one. It means to you that only one segment of business should cause changes to this particular piece of code.

If there is the same reason to change for two or more elements, you broke the DRY principle. For example, you have two classes or functions, that do similar things, and they have a single actor that could cause them to change. You broke the DRY principle.

If there are two reasons to change, two actors demanding changes, for only one element of code, you broke SRP.

That’s as simple as that. So, let’s go and do repeat yourself - if it’s necessary, of course ;)