REST service client: design, testing, monitoring

The purpose of this article is to present how to design, test, and monitor a REST service client. The article includes a repository with clients written in Kotlin using various technologies such as WebClient, RestClient, Ktor Client, Retrofit. It demonstrates how to send and retrieve data from an external service, add a cache layer, and parse the received response into domain objects.

Motivation #

Why do we need objects in the project that encapsulate the HTTP clients we use? To begin with, we want to separate the domain from technical details. The way we retrieve/send data and handle errors, which can be quite complex in the case of HTTP clients, should not clutter business logic. Next, testability. Even if we do not use hexagonal architecture in our applications, it’s beneficial to separate the infrastructure from the service layer, as it improves testability. Verifying an HTTP service client is not a simple task and requires consideration of many cases — mainly at the integration level. Having a separate “building block“ that encapsulates communication with the outside world makes testing much easier. Finally, reusability. A service client that has been written once can be successfully used in other projects.

Client Design #

As a case study, I will use an example implementation that utilizes WebClient for retrieving data from the Order Management Service,

an example service that might appear in an e-commerce site such as Allegro.

The heart of our client is the executeHttpRequest method, which is responsible for executing the provided HTTP request, logging, and error handling.

It is not part of the WebClient library.

class OrderManagementServiceClient(

private val orderManagementServiceApi: OrderManagementServiceApi,

private val clientName: String

) {

suspend fun getOrdersFor(clientId: ClientId): OrdersDto {

return executeHttpRequest(

initialLog = "[$clientName] Get orders for a clientId= $clientId",

request = { orderManagementServiceApi.getOrdersFor(clientId) },

successLog = "[$clientName] Returned orders for a clientId= $clientId",

failureMessage = "[$clientName] Failed to get orders for clientId= $clientId"

)

}

}

Full working example can be found here.

Client name #

I like to name clients using the convention: name of the service we integrate with, plus the suffix Client.

In the case of integration with the Order Management Service, such a class will be named OrderManagementServiceClient.

If the technology we use employs an interface to describe the called REST API (RestClient, WebClient, Retrofit),

we can name such an interface OrderManagementServiceApi — following the general pattern of the service name with the suffix Api.

These names may seem intuitive and obvious, but without an established naming convention, we might end up with a project where different integrations have the following suffixes: HttpClient, Facade, WebClient, Adapter, and Service. It’s important to have a consistent convention and adhere to it throughout the project.

API #

Methods of our clients should have names that reflect the communicative intention behind them.

To capture this intention, it is necessary to use a verb in the method’s name.

Typically, the correct name will have a structure of verb + resource name, for example, getOrders — for methods that retrieve resources.

If we want to narrow down the number of returned resources using filters or return a particular resource, I recommend adding the suffix “For” before the list of parameters.

Technically, these parameters will be part of the query or path parameters.

fun getOrdersFor(clientId: ClientId): OrdersDto

For methods responsible for creating resources, simply using the verb in the method name is enough, as the resource being passed as a parameter effectively conveys the intention of the method.

fun publish(event: InvoiceCreatedEventDto)

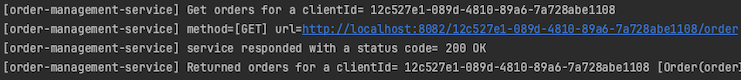

Logging #

When communicating with external service we’d like to log the beginning of the interaction, indicating our intention to fetch or send a resource, as well as its outcome. The outcome can be either a success, meaning receiving a response with a 2xx status code, or a failure.

Failure can be signaled by status codes (3xx, 4xx, 5xx), resulting from the inability to deserialize the received response into an object, exceeding the response time, etc. Generally, many things can go wrong. Depending on the cause of failure, we may want to log the interaction result at different levels (warn/error). There are critical errors that are worth distinguishing (error), and those that will occasionally occur (warn) and don’t require urgent intervention.

To filter logs related to a specific service while browsing through them, I like to include the client’s name within curly braces at the beginning of the logs.

For logging technical aspects of the communication, such as the URL called, HTTP method used, and response code,

we use filters (logRequestInfo, logResponseInfo) that are plugged in at the client configuration level in the createExternalServiceApi method.

inline fun <reified T> createExternalServiceApi(

webClientBuilder: WebClient.Builder,

properties: ConnectionProperties

): T =

webClientBuilder

.clientConnector(httpClient(properties))

.baseUrl(properties.baseUrl)

.defaultRequest { it.attribute(SERVICE_NAME, properties.clientName) }

.filter(logRequestInfo(properties.clientName))

.filter(logResponseInfo(properties.clientName))

.build()

.let { WebClientAdapter.create(it) }

.let { HttpServiceProxyFactory.builderFor(it).build() }

.createClient(T::class.java)

fun logRequestInfo(clientName: String) = ExchangeFilterFunction.ofRequestProcessor { request ->

logger.info {

"[$clientName] method=[${request.method().name()}] url=${request.url()}}"

}

Mono.just(request)

}

fun logResponseInfo(clientName: String) = ExchangeFilterFunction.ofResponseProcessor { response ->

logger.info { "[$clientName] service responded with a status code= ${response.statusCode()}" }

Mono.just(response)

}

Here’s an example of logged interaction for successfully fetching a resource.

To prevent redundancy in logging code across multiple clients, it is centralized inside executeHttpRequest method.

The only thing the developer needs to do is to provide a business-oriented description for the beginning of the interaction and its outcome (parameters: initialLog, successLog, failureMessage).

Why do I emphasize logging so much? Isn’t it enough to log only errors? After all, we have metrics that inform us about the performance of our clients. Metrics won’t provide us with the details of the communication, but logs will. These details can turn out to be crucial in the analysis of incidents, which may reveal, for example, incorrect data produced by our service.

Logs are like backups. We find out if we have them and how valuable they are only when they are needed, either because the business team requests an analysis of a particular case or when resolving an incident.

Error handling #

When writing client code, we aim to highlight maximally how we send/retrieve data and hide the “noise“ that comes from error handling.

In the case of HTTP clients, error handling is quite extensive but generic enough that the resulting code can be written once and reused across all clients.

In our example, error handling mechanism is hidden inside executeHttpRequest method.

It consists of two things: logging and throwing custom exceptions that encapsulate technical exceptions thrown by the underlying HTTP client.

What are the benefits of using custom exceptions? The very name of such a custom exception tells us exactly what went wrong.

For comparison, ExternalServiceIncorrectResponseBodyException seems to be more descriptive than DecodingException.

They also help group various technical exceptions that lead to the same cause, for example, an incorrect response object structure.

Additionally, based on these exceptions, visualizations can be created to show the state of our integration.

For example, we can create a table that will show how many exceptions of any given type were thrown by our clients within a specified period.

Having custom exceptions, we are 100% certain that these exceptions were thrown only by our clients.

Testing #

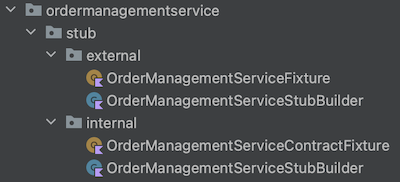

Stubs #

To verify different scenarios of our HTTP client, it is necessary to appropriately stub the called endpoints in tests. For this purpose, we will use the WireMock library.

It is quite important that the technical details of created stubs do not leak into the tests.

The test should describe the behavior being tested and encapsulate technical details.

For example, changing the accept/content-type header or making minor modifications to the called URL should not affect the test itself.

To achieve this, for each service for which we write a service client, we create an object of type StubBuilder.

The StubBuilder allows hiding the details of stubbing and verification behind a readable API.

It takes on the impact of changes to the called API, protecting our test from modification.

It fulfills a similar role to the Page Object Pattern in end-to-end tests for web apps.

orderManagementServiceStub.willReturnOrdersFor(clientId, response = ordersPlacedBySomeCustomer())

StubBuilders for services that return data come in two flavors - internal and external.

When testing a service client, we want to have great flexibility in simulating responses.

Therefore, StubBuilders from the internal package will model response objects as a string. This allows us to simulate any scenario.

In end-to-end tests, where a given service is part of the bigger process, such flexibility is not necessary; in fact, it is not even recommended.

Therefore, StubBuilders from the external package model responses using real objects.

All StubBuilders from the external packages are declared in the class ExternalServiceStubs, to which a reference is located in the base class for

all integration tests, BaseIntegrationTest. This allows us to have very easy access to all external service stubs in our integration tests.

stub.orderManagementService().willReturnOrdersFor(clientId, response = ordersPlacedBySomeCustomer())

Reading the code above, we immediately know which service is being interacted with (Order Management Service) and what will be returned from it (Orders). The technical details of the stubbed endpoint have been hidden inside the StubBuilder object. Tests should emphasize “what” and encapsulate “how.” This way, they can serve as documentation.

Test Data #

The data returned by our stubs can be prepared in three ways:

- Read the entire response from a file/string.

- Prepare the response using real objects used in the service for deserializing responses from called services.

- Create a set of separate objects modeling the returned response from the service for testing purposes and use them to prepare the returned data.

Which option to choose? To answer this question, we should analyze the advantages and disadvantages of each approach.

Option A — read response from a file/string. Response creation is very fast and simple. It allows verifying the contract between the client and the supplier (at least at the time of writing the test). Imagine that during refactoring, one of the fields in the response object accidentally changes. In such a case, client tests using this approach will detect the defect before the code reaches production.

@Test

fun `should return orders for a given clientId`(): Unit = runBlocking {

// given

val clientId = anyClientId()

orderManagementServiceStub.willReturnOrdersFor(clientId, response = ordersPlacedBySomeCustomer())

// when

val response: OrdersDto = orderManagementServiceClient.getOrdersFor(clientId)

// then

response shouldBe OrdersDto(listOf(OrderDto("7952a9ab-503c-4483-beca-32d081cc2446")))

}

On the other hand, keeping data in files/strings is difficult to maintain and reuse. Programmers often copy entire files for new tests, introducing only minimal changes. There is a problem with naming these files and refactoring them when the called service introduces an incompatible change.

Option B — Use real response objects. It allows writing one-line, readable assertions and maximally reusing already created data, especially using test data builders.

@Test

fun `should return orders for a given clientId`(): Unit = runBlocking {

// given

val clientId = anyClientId()

val clientOrders = OrderManagementServiceFixture.ordersPlacedBySomeCustomer()

orderManagementServiceStub.willReturnOrdersFor(clientId, response = clientOrders)

// when

val response: OrdersDto = orderManagementServiceClient.getOrdersFor(clientId)

// then

response shouldBe clientOrders

}

However, accidental change of field name which results in the contract violation between the client and supplier won’t be caught. As a result, we might have perfectly tested communication in integration tests that will not work in production.

Option C — create a set of separate response objects. It has all the advantages of options A and B, including maintainability, reusability, and verification of the contract between the client and the supplier. Unfortunately, maintaining a separate model for testing purposes comes with some overhead and requires discipline on the developers’ side, which can be challenging to maintain.

Which option to choose? Personally, I prefer a hybrid of options A and B. For the purpose of testing the “happy path“ in client tests, I return a response that is entirely stored as a string (alternatively, it can be read from a file). Such a test allows not only to verify the contract but also the correctness of deserializing the received response into a response object. In other tests (cache, adapter, end-to-end), I create responses returned by the stubbed endpoint using production response objects.

It’s worthwhile to keep sample test data in dedicated classes, such as a Fixture class, for each integration (for example OrderManagementServiceFixture).

This allows the reuse of test data and enhances the readability of the tests themselves.

Test Scenarios #

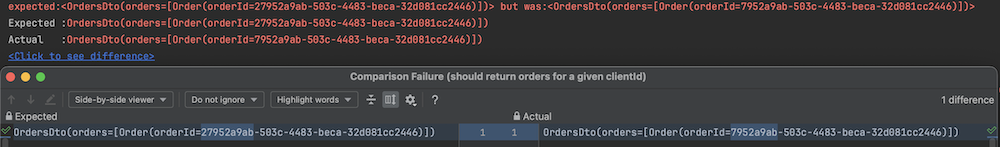

Happy Path #

Fetching a resource — verification whether the client can retrieve data from the previously stubbed endpoint and deserialize it into a response object.

@Test

fun `should return orders for a given clientId`(): Unit = runBlocking {

// given

val clientId = anyClientId()

orderManagementServiceStub.willReturnOrdersFor(clientId, response = ordersPlacedBySomeCustomer())

// when

val response: OrdersDto = orderManagementServiceClient.getOrdersFor(clientId)

// then

response shouldBe OrdersDto(listOf(OrderDto("7952a9ab-503c-4483-beca-32d081cc2446")))

}

An essential part of the test for the “happy path“ is verification of the contract between the client and the supplier.

The ordersPlacedBySomeCustomer method returns a sample response guaranteed by the supplier (Order Management Service).

On the client side, in the assertion section, we check if this message has been correctly deserialized into a response object.

Instead of comparing individual fields with the expected value, I highly recommend comparing entire objects (returned and expected).

It gives us confidence that all fields have been compared. In the case of regression, modern IDEs such as IntelliJ indicate exactly where the problem is.

Sending a resource — verification whether the client sends data to the specified URL in a format acceptable by the previously stubbed endpoint. In the following example, I test publishing an event to Hermes, a message broker built on top of Kafka widely used at Allegro.

@Test

fun `should successfully publish InvoiceCreatedEvent`(): Unit = runBlocking {

// given

val invoiceCreatedEvent = HermesFixture.invoiceCreatedEvent()

stub.hermes().willAcceptInvoiceCreatedEvent()

// when

hermesClient.publish(invoiceCreatedEvent)

// then

stub.hermes().verifyInvoiceCreatedEventPublished(event = invoiceCreatedEvent)

}

Stubbed endpoints for methods accepting request bodies (e.g., POST, PUT) should not verify the values of the received request body but only its structure.

fun willAcceptInvoiceCreatedEvent() {

WireMock.stubFor(

invoiceCreatedEventTopic()

.withRequestBody(WireMock.matchingJsonPath("$.invoiceId"))

.withRequestBody(WireMock.matchingJsonPath("$.orderId"))

.withRequestBody(WireMock.matchingJsonPath("$.timestamp"))

.willReturn(

WireMock.aResponse()

.withFixedDelay(responseTime)

.withStatus(HttpStatus.OK.value())

)

)

}

We verify the content of the request body in the assertion section. Here, we also want to hide the technical aspects of assertions behind a method.

stubs.hermes().verifyInvoiceCreatedEventPublished(event = invoiceCreatedEvent)

fun verifyInvoiceCreatedEventPublished(event: InvoiceCreatedEventDto) {

WireMock.verify(

1,

WireMock.postRequestedFor(WireMock.urlPathEqualTo(INVOICE_CREATED_URL))

.withRequestBody(WireMock.matchingJsonPath("$.invoiceId", WireMock.equalTo(event.invoiceId)))

.withRequestBody(WireMock.matchingJsonPath("$.orderId", WireMock.equalTo(event.orderId)))

.withRequestBody(WireMock.matchingJsonPath("$.timestamp", WireMock.equalTo(event.timestamp)))

)

}

Combining stubbing and request verification in one method is not recommended. Creating stubs in this way makes their usage less convenient since not every test requires detailed verification of what is being sent in the request body. The vast majority of tests will stub the endpoint based on the principle: accept a given request as long as its structure is preserved and will verify hypotheses other than the content of the request body (mainly end-to-end tests).

Client-side errors #

For 4xx type errors, we want to verify the following cases:

- The absence of the requested resource signaled by the response code 404 and a custom exception

ExternalServiceResourceNotFoundException - Validation error signaled by the response code 422 and a custom exception

ExternalServiceRequestValidationException - Any other 4xx type errors should be cast to an

ExternalServiceClientException

@ParameterizedTest(name = "{index}) http status code: {0}")

@MethodSource("clientErrors")

fun `when receive response with 4xx status code then throw exception`(

exceptionClass: Class<Exception>,

statusCode: Int,

responseBody: String?

): Unit = runBlocking {

// given

val clientId = anyClientId()

orderManagementServiceStub.willReturnOrdersFor(clientId, status = statusCode, response = responseBody)

// when

val exception = shouldThrowAny {

orderManagementServiceClient.getOrdersFor(clientId)

}

// then

exception.javaClass shouldBeSameInstanceAs exceptionClass

exception.message shouldContain clientId.clientId.toString()

exception.message shouldContain properties.clientName

}

In distributed systems, a 404 response code is quite common and may result from temporary inconsistency across the entire system.

Its occurrence is signaled by the ExternalServiceResourceNotFoundException and a warning-level log.

Here, we are more interested in the scale of occurrences, which is why we use metrics, than analyzing individual cases, hence we log such cases at the warning level.

The situation looks a bit different in the case of responses with a code of 422.

If the request is rejected due to validation errors, either our service has a defect and produces incorrect data,

or we receive incorrect data from external services (which is why it’s crucial to log what we receive from external services).

Alternatively, the error may be on the recipient side in the logic validating the received request. It’s worth analyzing each such case, which is why

errors of this type are logged at the error level and signaled by the ExternalServiceRequestValidationException.

Other errors from the 4xx family occur less frequently.

They are all marked by the ExternalServiceClientException exception and logged at the error level.

Server-side errors #

Regardless of the reason for a 5xx error, all of them are logged at the warn level because we have no control over them.

They are signaled by the ExternalServiceServerException exception. Similar to 404 errors, we are more interested in aggregate information

about the number of such errors rather than analyzing each case individually, hence the warn log level.

In tests, we consider two cases because the response from the service may or may not have a body. If the response has a body, we want to log it.

Read Timeout #

Our HTTP client should have a finite response timeout configured, so it’s worthwhile to write an integration test that verifies the client’s configuration.

Simulating the delay of the stubbed endpoint can be achieved using the withFixedDelay method from wiremock.

@Test

fun `when service returns above timeout threshold then throw exception`(): Unit = runBlocking {

// given

val clientId = anyClientId()

orderManagementServiceStub

.withDelay(properties.readTimeout.toInt())

.willReturnOrdersFor(

clientId,

response = ordersPlacedBySomeCustomer()

)

// when

val exception = shouldThrow<ExternalServiceReadTimeoutException> {

orderManagementServiceClient.getOrdersFor(clientId)

}

// then

exception.message shouldContain clientId.clientId.toString()

exception.message shouldContain properties.clientName

}

No, this is not testing properties in tests. This test ensures that the configuration derived from properties has indeed been applied to the given client. Ensuring a response within a specified time frame might be part of non-functional requirements and requires verification.

Invalid Response Body #

Considered cases:

- Response body does not contain required field.

- Response body is empty.

- Response has an incorrect format.

Errors of this type are signaled through ExternalServiceIncorrectResponseBodyException and logged at the error level.

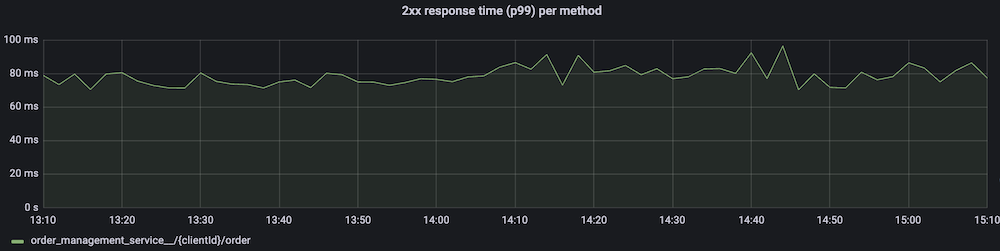

Metrics #

When dealing with HTTP clients, it’s essential to monitor several aspects: response times, throughput, and error rates.

To differentiate metrics generated by different clients easily, it’s advisable to include a service.name tag with the respective client’s name.

In HTTP clients offered by the Spring framework (WebClient, RestClient), metrics are enabled out-of-the-box if we create them using predefined builders (WebClient.Builder, RestClient.Builder). However, for other technologies, third-party solutions must be employed. In Allegro, we have a set of libraries that allows us to quickly create new HTTP clients in the most popular technologies that provide support for our infrastructure. As a result, all clients generate consistent metrics by default tailored to our dashboards.

Response Time #

Measuring the response time of HTTP clients allows us to identify bottlenecks. At which percentile should we set such a metric? Generally, the more requests a client generates, the higher the percentile we should aim for. Sometimes, issues become visible only at high percentiles (P99, P99.9) for a very high volume of requests.

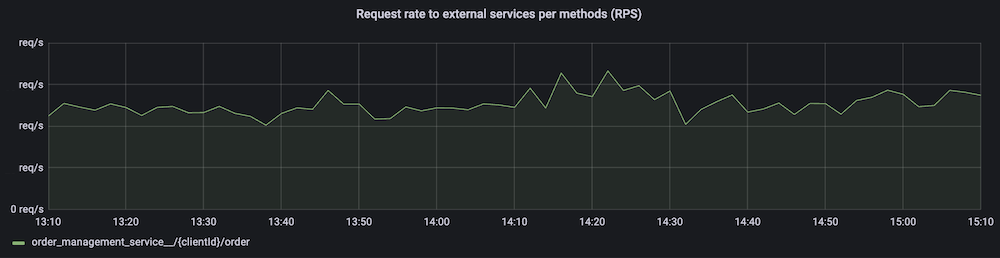

Throughput #

Number of requests that our application sends to external services per second (RPS). An auxiliary metric for the response time metric, where response time is always considered in the context of the generated traffic.

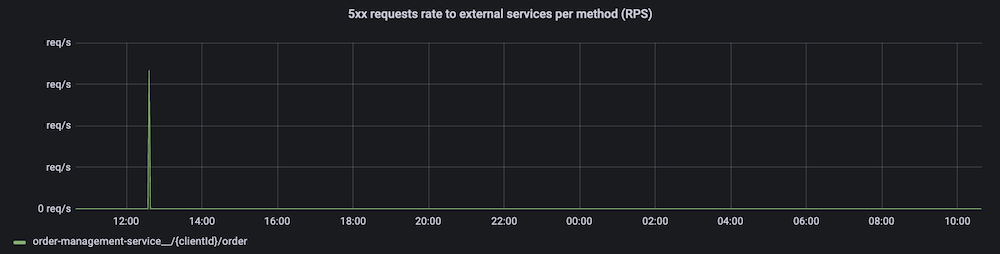

Error Rate #

Counting responses with codes 4xx/5xx. Here, we are interested in visualizing how many such errors occurred within a specific timeframe. The number of errors we analyze depends on the overall traffic, therefore, both metrics should be expressed in the same units, usually requests per second. For high traffic and a small number of errors, we can expect that the presented values will be on the order of thousandths.

Summary #

Microservices Architecture relies heavily on network communication. The most common method of communication is REST API calls between different services. Writing integration code involves more than just invoking a URL and parsing a response. Logs, error handling, and metrics are crucial for creating a stable and fault-tolerant microservices environment. Developers should have tools that take care of these aspects, enabling fast and reliable development of such integrations. However, tools alone are insufficient. We also need established rules and guidelines that allow us to write readable and maintainable code, both in production and tests.

Code examples #

To explore comprehensive examples, including the usage of WebClient and other HTTP clients, check out the GitHub repository.