Making Webflux code readable with Kotlin coroutines

Recently, our crucial microservice delivering listing data switched to Spring WebFlux. A non-blocking approach gave us the possibility to reduce the number of server worker threads compared to Spring WebMvc. The reactive approach helped us to effectively build a scalable solution. Also, we entered the world of functional programming where code becomes declarative:

- statements reduced to the minimum

- immutable data preferred

- no side effects

- quite a neat chaining of method calls causing it easier to understand.

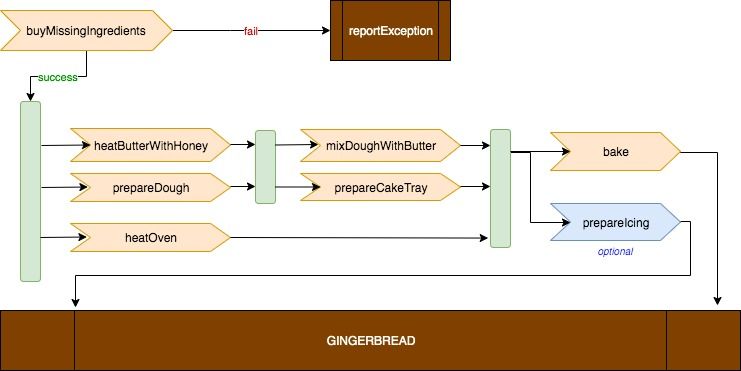

Assume the business requirement is to bake gingerbread optimally. The following diagram should help to understand the recipe steps:

In the beginning, when not very complicated logic was translated into webflux, we felt comfortable with the chaining of two or three lines of code. However, the more you get into it, the more complicated it becomes. Some new additions made the code unreadable. Finally, we constructed such a monster:

fun prepareGingerbread(existingIngredients: Set<Ingredient>): Mono<Gingerbread>? {

return buyMissingIngredients(requiredIngredients, existingIngredients)

?.filter { succeeded -> succeeded }

//.map(succeeded -> heatOvenToDegrees(180L)) //oven should be heated at this point

?.flatMap { _ -> heatButterWithHoney() }

?.zipWith(prepareDough())

?.map { heatedAndDoughTuple -> mixDoughWithButter(heatedAndDoughTuple.t1, heatedAndDoughTuple.t2) }

?.zipWith(prepareCakeTray())

?.zipWith(heatOven()) { contentAndVesselTuple,ovenHeated ->

bake(ovenHeated, contentAndVesselTuple.t1, contentAndVesselTuple.t2)}

?.zipWith(prepareIcing()) { baked, icing -> Gingerbread(baked, icing) }

}

You may think now: who invented such a flow? But in the real world things are even much more complicated.

When the project was evolving, one of the challenges was to add a feature by calling heatOven() method (placed in comment).

Of course, one could say: “yes, you may introduce a new data structure and save transitional state in it”.

And yes, it’s true for not sophisticated microservices. But not easy for a critical service dependent on a dozen other services,

with business logic sensitive to change, executing thousands of request per second.

So let’s get back to our monster. Imagine that a new feature has been requested, further increasing the level of complexity. We said: it is not possible, breaking all the coaching rules. Then we realized there was a solution, inspired by Exploring Coroutines in Kotlin by Venkat Subramariam presented during KotlinConf 2018: In Kotlin Coroutine Structure Of [Imperative], Synchronous Code is the same as Asynchronous Code

What are Coroutines? #

Coroutines are so-called lightweight threads that are used to perform tasks asynchronously. As a result, it is a technique of non-blocking programming. Looking closer, a coroutine is not a thread, internally it uses the mechanism of continuations. Roughly speaking, we can say that famous callback-hell is hidden behind the scenes. What is important: no thread means no context switching. In other words: a coroutine represents a sequence of sub-tasks that are to be executed in a guaranteed order. Having a traditionally-looking piece of code, calling a special function marked as suspending means a new sub-task is being launched within the coroutine.

Process of code migration from Java to Kotlin with coroutines #

- convert a few classes into Kotlin. In this step I used IntelliJ IDEA functionality: Convert Java to Kotlin, but it requires some experience to do it properly (as converted code often needs to be refined manually).

- run tests, make sure they are green

- analyze which variables are relevant (those on which other things depend or those requiring network calls)

- extract these variables from a complicated chain as they could be used in a good old-fashioned procedural style

- expressions for computing variables that previously were of mono/flux type enhance with:

awaitFirstOrDefault(default)(replacing map/flatMap chaining). This suspend function awaits for the first value from the given observable without blocking a thread and returns the resulting value (or the default value if none is emitted). As a result, the variable ofMono<T>becomes just ofTtype. Note that other similar extension functions may also be used:awaitFirst,awaitFirstOrDefault,awaitFirstOrElse,awaitFirstOrNull,awaitLast,awaitSingle - use those variables writing easy code, where business logic is separated (not nested in multi-level call chains)

- wrap the whole body function into

mono {}coroutine builder block (from kotlinx-coroutines-reactor package). Note that the last statement in a block is being returned as a value. This kind of reactive stream is called a cold mono (cold - produces a new copy of data for each subscriber, hot mono/flux - publishes data regardless of subscribers’ presence). - make sure the code compiles and tests pass

The result after migration to Kotlin with coroutines #

fun prepareGingerbread(existingIngredients: Set<Ingredient>): Mono<Gingerbread> {

return mono {

buyMissingIngredients(requiredIngredients, existingIngredients)?.awaitFirstOrDefault(false)

val oven = heatOven()

val heat = heatButterWithHoney()

val dough = prepareDough()

val mixedDoughWithButter = mixDoughWithButter(heat?.awaitFirstOrDefault(false), dough.awaitFirstOrDefault(false))

val tray = prepareCakeTray()

val baked = bake(oven.awaitFirstOrDefault(false), mixedDoughWithButter, tray.awaitFirstOrDefault(false))

val icing = prepareIcing().awaitFirstOrDefault(false)

Gingerbread(baked, icing)

}

}

Synthetic tests #

I prepared two simple projects: kotlin-coroutines-gingerbread and auxiliary kotlin-coroutines-server for performance analysis of using various clients. Gingerbread service contains a few endpoints serving the same data but with the use of different technologies:

- /blockingRestTemplate - standard Spring Rest Template (blocking)

- /suspendingPureCoroutines - uses Rest Template but wrapped into coroutine (still blocking)

- /suspendingFuelCoroutines - uses suspending client and coroutines: Fuel (non-blocking)

- /webfluxPureReactive - uses Spring WebClient underneath in reactive flow

- /webfluxReactiveCoroutines - the same Spring WebClient but wrapped into mono coroutine builder.

Tests were run on a single machine:

- in one terminal an auxiliary server is started. It exposes a few endpoints with random delay in order to simulate typical backend micro-service network traffic,

- in the second - gingerbread application requesting these endpoints (with read timeout set to 80ms).

To verify various techniques, I used vegeta and its attack command for sending

huge traffic against the gingerbread server. I am aware that the test was not run under perfect laboratory conditions, but tests show

general possibilities of selected client techniques.

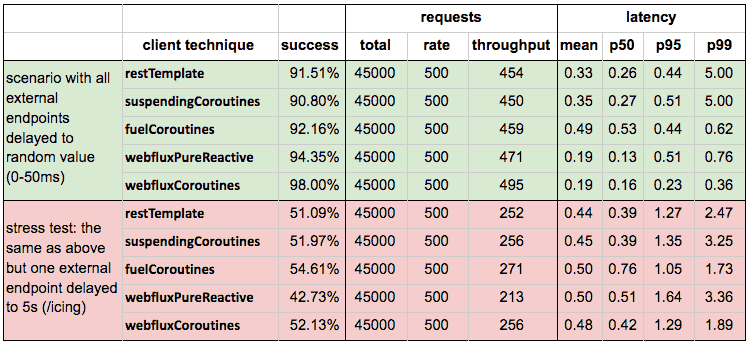

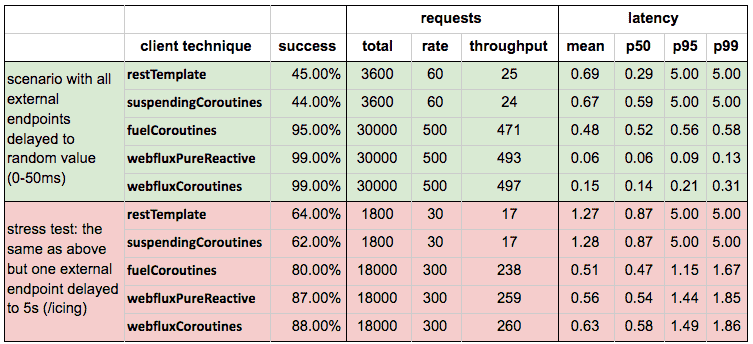

Tests results (with 64 server workers) #

It is worth to notice that netty worker count was set to 64 in order to provide thread resources for restTemplate blocking flow (alternatively a dedicated thread pool may be used instead). Normally it is set to the number of CPU cores (but at least 2), which is optimized for reactive techniques. Without this custom netty configuration, restTemplate performance is much lower compared to webflux; it is shown in the table below:

Note that blocking flow performs significantly worse even at a lower rate. Of course, more server threads mean more memory and CPU context switching. And in the long run, it is not a scalable solution.

Conclusions from testing #

- It is important what kind of client is selected in implementation. Application with blocking clients - without careful configuration of thread pools - cannot handle traffic as high as non-blocking ones.

- Using only coroutines may not be enough: for suspendingCoroutines endpoint we can see lower throughput (thread pool misconfiguration).

For

fuelclient we observe a quite high rate - it is sincefuelclient method is suspendable. - The most important - there is no significant difference in performance of webflux reactive and webflux wrapped into coroutines.

Summary #

There are a few essential benefits of migrating from typical webflux code to webflux combined with coroutines:

- the obvious is much more readable and maintainable code. There is no need to carefully use nestings only to show where we are in the sophisticated flow

- debugging is as easy as standard procedural code

- requests are quite well isolated. Note that if a blocking API call is placed inside a coroutine, then it should be guarded by its own thread pool coroutine context. Even if such a pool is exhausted due to a heavy load, by the fact that this API call is wrapped into a suspend function, the main thread will never be blocked.

However, coroutines are not always recommended:

- when a project uses quite simple flow. Remember that coroutines have some overhead as the complicated mechanism behind the scenes is not for free.

- some claim coroutines in Kotlin are over-engineered, low-level and very hard to understand for the user. There is a learning curve and the developer needs to follow some rules that are not always easy to understand and to remember.

But nevertheless, coroutines are worth deep consideration!