Migrating a microservice to Spring WebFlux

Reactive programming has been a hot topic on many conference talks for at least several months. It’s effortless to find simple code examples and tutorials and to apply them to greenfield projects. Things become a little bit more complicated when production services with millions of users and thousands of requests per second need to be migrated from existing solutions. In this article, I would like to discuss migration strategy from Spring Web MVC to Spring WebFlux by the example of one of the Allegro microservices. I’m going to show some common pitfalls as well as how performance metrics in production were affected by migration.

Motivation for change #

Before exploring the migration strategy in detail, let’s discuss the motivation for the change first.

One of the microservices, which is developed and maintained by my team, was involved in the significant Allegro outage

on 18th of July 2018 (see more details in postmortem).

Although our microservice was not the root cause of problems, some of the instances also crashed because of thread pools saturation.

Ad hoc fix was to increase thread pool sizes and to decrease timeouts in external service calls; however, this was not sufficient.

The temporary solution only slightly increased throughput and resilience for external services latencies.

We decided to switch to a non-blocking approach to completely get rid of thread pools as the foundation for concurrency.

The other motivation to use WebFlux was the new project which complicated the external service calls flow

in our microservice.

We faced the challenge to keep the codebase maintainable and readable regardless of increasing complexity.

We saw WebFlux more friendly than our previous solution based on Java 8 CompletableFuture to model complex flow.

What is Spring WebFlux? #

Let’s start from understanding what and what for is Spring WebFlux. Spring WebFlux is reactive-stack web framework, positioned as a successor of well-known and widely used Spring Web MVC. The primary purposes of creating a new framework were to support:

- a non-blocking approach which makes it possible to handle concurrency with a small number of threads and to scale effectively,

- functional programming, which helps write more declarative code with the usage of fluent APIs.

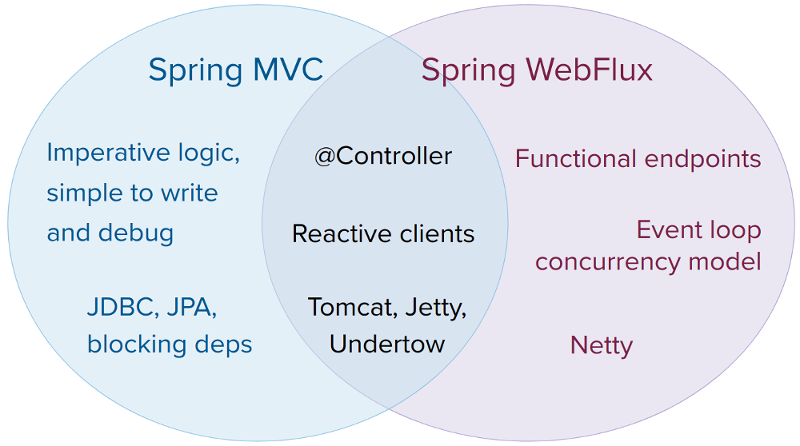

The most important new features are functional endpoints, event loop concurrency model and reactive Netty server. You might think that by introducing a whole new stack and paradigm, compatibility between WebFlux and Web MVC has been broken. In fact, Pivotal worked on making coexistence as painless as possible.

We are not forced to migrate every aspect of our code

to the new approach. We can easily pick some reactive stuff (like

reactive WebClient)

and move forward doing small steps.

We can even omit some features if we don’t feel that they provide real value but have a significant cost of change.

For example, if you’re OK with @Controller annotations - they work well with the reactive stack.

Also if you’re familiar with Undertow or Tomcat configuration -

that’s completely fine, you don’t have to use Netty server.

When (not) to migrate? #

Every emerging technology tends to have its hype cycle. Playing with a new solution, especially in a production environment solely because it’s fresh, shiny and buzzy — can lead to frustration and sometimes catastrophic results. Every software vendor wants to advertise his product and convince clients to use it. However, Pivotal behaves very responsibly, paying close attention to situations when migration to WebFlux is not the best idea. Part 1.1.4 of official documentation covers that in details. The most important points are:

- Do not change things that work fine. If you don’t have performance or scaling issues in your service — find a better place to try WebFlux.

- Blocking APIs and WebFlux are not the best friends. They can cooperate, but there is no efficiency gain from migration to reactive stack. You should take this advice with a grain of salt. When only some dependencies in your code are blocking — there are elegant ways to deal with it. When they are the majority — your code becomes much more complicated and error-prone — one blocking call can lock the whole application.

- The learning curve for a team, especially if it doesn’t have experience with reactive stuff, can be steep. You should pay much attention to the human factor in the migration process.

Let’s talk a little bit about performance. There is much misunderstanding about that. Going reactive doesn’t mean an automatic performance boost. Moreover, WebFlux documentation warns us that more work is required to do things the non-blocking way. However, the higher the latency per call or the interdependency among calls, the more dramatic the benefits. Reactiveness shines here — waiting for other service response doesn’t block the thread. Thus fewer threads are necessary to obtain the same throughput, and fewer threads mean less memory used.

It’s always recommended to check independent sources to avoid framework authors’ bias. An excellent source of opinion when it comes to choosing a new technology is Technology Radar by ThoughtWorks. They report system throughput and an improvement in code readability after migration to WebFlux. On the other hand, they point out that a significant shift in thinking is necessary to adopt WebFlux successfully.

To summarize, there are four indicators that migration to WebFlux could be a good idea for the project:

- Current technology stack doesn’t solve the problem with adequate performance and scalability.

- There are a lot of calls to external services or databases with possibly slow responses.

- Existing blocking dependencies could be easily replaced with reactive ones.

- The development team is open to new challenges and willing to learn.

Migration strategy #

Based on our migration experience, I’d like to introduce the 3-stage migration strategy. Why 3 stages? When looking at our process, it looked strangely familiar to me. We got the starters first, to sharpen the appetite. Then we went for the main dish, rewriting and learning from our mistakes. The dessert, like a cake with a cherry on top, made us smile thinking about all the hard work we did. One thing to remember — if we talk about live service with a large codebase, thousands of requests per second and millions of users — rewriting from scratch is a considerable risk. Let’s see how to migrate an application from Spring Web MVC to Spring WebFlux in subsequent, minor steps, which allow a smooth transition from blocking to the non-blocking world.

Stage 1, starter — migrating a small piece of code #

In general, there is a good practice to try new technologies on non-critical parts of the system first.

Going reactive is not an exception. The idea of this stage is to find only one non-critical feature,

encapsulated in one blocking method call, and to rewrite it to non-blocking style.

Let’s try to do this on an example of the blocking method which uses RestTemplate to retrieve the result from an external

service.

Pizza getPizzaBlocking(int id) {

try {

return restTemplate.getForObject("http://localhost:8080/pizza/" + id, Pizza.class);

} catch (RestClientException ex) {

throw new PizzaException(ex);

}

}

We pick only one thing from the rich set of WebFlux features — reactive WebClient — and use it to rewrite this method in a non-blocking way.

Mono<Pizza> getPizzaReactive(int id) {

return webClient

.get()

.uri("http://localhost:8080/pizza/" + id)

.retrieve()

.bodyToMono(Pizza.class)

.onErrorMap(PizzaException::new);

}

Now it’s time to wire our new method with the rest of the application. The non-blocking method returns Mono,

but we need a plain type instead. We can use the .block() method to retrieve the value from Mono.

Pizza getPizzaBlocking(int id) {

return getPizzaReactive(id).block();

}

Eventually, our method is still blocking. However, it utilizes a non-blocking library inside. The main goal of this stage is to get familiar with the non-blocking API. This change should be transparent to the rest of the application, easily testable and deployable into the production environment.

Stage 2, main dish — converting a critical path to the non-blocking approach #

After converting a small piece of code using WebClient, we are ready to go further. The goal of the second stage is to convert the critical path of the application to non-blocking in all layers — from the HTTP clients, through classes which process external service responses, to the controllers. The important thing at this stage is to avoid rewriting all the code. The less critical parts of the application, such as those with no external calls or rarely used, should be left as is. We need to focus on areas where non-blocking approach reveals its benefits.

//parallel call to two services using Java8 CompletableFuture

Food orderFoodBlocking(int id) {

try {

return CompletableFuture.completedFuture(new FoodBuilder())

.thenCombine(CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> pizzaService.getPizzaBlocking(id), executorService), FoodBuilder::withPizza)

.thenCombine(CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> hamburgerService.getHamburgerBlocking(id), executorService), FoodBuilder::withHamburger)

.get()

.build();

} catch (ExecutionException | InterruptedException ex) {

throw new FoodException(ex);

}

}

//parallel call to two services using Reactor

Mono<Food> orderFoodReactive(int id) {

return Mono.just(new FoodBuilder())

.zipWith(pizzaService.getPizzaReactive(id), FoodBuilder::withPizza)

.zipWith(hamburgerService.getHamburgerReactive(id), FoodBuilder::withHamburger)

.map(FoodBuilder::build)

.onErrorMap(FoodException::new);

}

Blocking parts of the system can be easily merged with

non-blocking code using .subscribeOn() method. We can use one of the default Reactor

schedulers as well as thread pools created on our own and provided by ExecutorService.

Mono<Pizza> getPizzaReactive(int id) {

return Mono.fromSupplier(() -> getPizzaBlocking(id))

.subscribeOn(Schedulers.fromExecutorService(executorService));

}

Additionally, only a small change in controllers is enough — change the return type from Foo to Mono<Foo> or Flux<Foo>.

It works even in Spring Web MVC - you don’t need to change the whole application’s stack to reactive.

Successful implementation of Stage 2 gives us all the main benefits of the non-blocking approach.

It’s time to measure and check if our problem is solved.

Stage 3, dessert — let’s change everything to WebFlux! #

We can do much more after Stage 2. We can rewrite the less critical parts of the code and use Netty server instead of servlets.

We can also get rid of @Controller annotations and rewrite endpoints to functional style,

although this is a matter of style and personal preferences rather than performance.

The critical question here is: what is the cost of those advantages? The code can be refactored all the time

and often it’s challenging to define the “good enough” point.

We didn’t decide to go further in our case. Rewriting the whole codebase would require much work.

The Pareto principle

turned out to be valid one more time. We felt that we had achieved a significant gain

and subsequent benefits have a relatively higher cost. As a general rule — it’s good to get all the perks

of WebFlux when we write a new service from scratch. On the other hand, it’s usually better to do as little work

as possible when we refactor an existing (micro)service.

Migration traps - lessons learned #

As I told earlier, migrating the code to non-blocking requires a significant shift in thinking. My team is not an exception — we fell into a few traps caused mainly by thinking rooted in blocking and imperative coding practice. If you plan to rewrite some code to WebFlux — here are some ready and concrete takeaways for you!

Issue 1 - hanging integration tests in the build server #

Excellent test coverage of the code is the best friend of safe refactor. Especially integration tests could confirm our feeling that everything was OK after rewriting a big part of the application. In our case the majority of them were framework and even programming language agnostic — they queried the service under test with HTTP requests. Unfortunately, we noticed that our integration tests started to hang sometimes. It was an alarming signal — after migrating to WebFlux, the service should behave the same from the client’s point of view. After a few days of research, we finally found that Wiremock (mocking library used in our test) was not fully compatible with WebFlux starter. After further investigation, we learned that tests worked fine with webmvc starter. GitHub issue #914 covers that in details.

The lessons learned:

- Double check that your test libraries fully support WebFlux.

- Do not change spring-boot-starter dependency from webmvc to webflux at an early stage of refactoring. Try to rewrite code to non-blocking and change application type to reactive only if everything works fine with servlet application type.

Issue 2 - hanging unit tests #

We used Groovy + Spock as the foundation of unit tests.

Although WebFlux gives new exciting testing possibilities,

we tried to adapt existing unit tests to non-blocking reality with the least effort possible.

When some method is converted to return Mono<Foo> instead of Foo, it’s usually enough to follow this method call

in the test with .block(). Otherwise, stubs and mock configured to return foo, now should wrap it with reactive type,

usually returning Mono.just(foo).

The theory seems simple, but our tests started to hang. Fortunately, in a reproducible way. What was the problem?

In classic, blocking approach, when we forget (or intentionally omit) to configure some method call in stub or mock,

it just returns null. In many cases, it doesn’t affect the test. However, when our stubbed method returns a reactive type,

misconfiguration may cause it to hang, because expected Mono or Flux never resolves.

The lesson learned:

stubs or mocks of methods returning reactive type, called during test execution, which previously implicitly returned

null, must now be explicitly configured to return at least Mono.empty() or Mono.just(some_empty_object).

Issue 3 - lack of subscription #

WebFlux beginners sometimes forget that reactive streams tend to be as lazy as possible. Due to a lacking subscription, the following function never prints anything to console:

Food orderFood(int id) {

FoodBuilder builder = new FoodBuilder().withPizza(new Pizza("margherita"));

hamburgerService.getHamburgerReactive(id).doOnNext(builder::withHamburger);

//hamburger will never be set, because Mono returned from getHamburgerReactive() is not subscribed to

return builder.build();

}

The lesson learned:

every Mono and Flux should be subscribed. Returning reactive type in a controller is such a kind of implicit subscription.

Issue 4 - .block() in Reactor thread #

As I showed before (in Stage 1), .block() is sometimes used to join a reactive function to blocking code.

Food getFoodBlocking(int id) {

return foodService.orderFoodReactive(id).block();

}

Calling this function isn’t possible within Reactor thread. Such an attempt causes the following error:

block()/blockFirst()/blockLast() are blocking, which is not supported in thread reactor-http-nio-2

Explicit .block() usages are only allowed within other threads (see .subscribeOn()).

It’s helpful that the Reactor throws an exception and informs us about the problem. Unfortunately,

many other scenarios allow inserting blocking code into Reactor thread, which is not automatically detected.

The lesson learned: .block() can be used only in code executed under scheduler.

Even better is to avoid using .block() at all.

Issue 5 - blocking code in Reactor thread #

Nothing prevents us from adding blocking code to a reactive flow.

Moreover, we don’t need to use .block() - we can unconsciously introduce blocking by using a library which

can block the current thread. Consider the following samples of code. The first one resembles proper, “reactive” delay.

Mono<Food> getFood(int id) {

return foodService.orderFood(id)

.delayElement(Duration.ofMillis(1000));

}

The other sample simulates a dangerous delay, which blocks the subscriber thread.

Mono<Food> getFood(int id) throws InterruptedException {

return foodService

.orderFood(id)

.doOnNext(food -> Thread.sleep(1000));

}

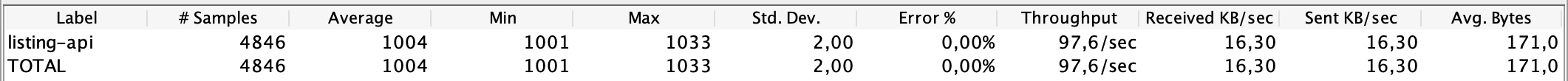

At a glance, both versions seem to work. When we run this application on localhost and try to request a service, we can see similar behavior. “Hello, world!” is returned after 1 s delay. However, this observation is hugely misleading. Our service response changes drastically under higher traffic. Let’s use JMeter to obtain some performance characteristics.

Both versions were queried using 100 threads. As we can see, the version with reactive delay (upper) works well under heavy load, providing constant delay and high throughput. On the other hand, the version with blocking delay (lower) cannot serve any considerable traffic. Why is this so dangerous? If a delay is associated with external service calls, everything works fine as long as the other service responds quickly. It’s a ticking time bomb. Such code can live in a production environment even several days and cause a sudden outage when you least expect it.

The lessons learned:

- Always double check libraries used in a reactive environment.

- Do performance test of your applications, especially taking into consideration the latency of external calls.

- Use special libraries such as BlockHound, which give invaluable help with detecting hidden blocking calls.

Issue 6 - WebClient response not consumed #

Documentation of WebClient .exchange() method clearly states:

You must always use one of the body or entity methods of the response to ensure resources are released.

Chapter 2.3 of official WebFlux documentation

gives us similar information.

This requirement is easy to miss, mainly when we use .retrieve() method, which is a shortcut to .exchange().

We stumbled upon such an issue. We correctly mapped the valid response to an object and wholly ignored the response in case of an error.

Mono<Pizza> getPizzaReactive(int id) {

return webClient

.get()

.uri("http://localhost:8080/pizza/" + id)

.retrieve()

.onStatus(HttpStatus::is5xxServerError, clientResponse -> Mono.error(new Pizza5xxException()))

.bodyToMono(Pizza.class)

.onErrorMap(PizzaException::new);

}

The code above works very well as long as the external service returns valid responses. Shortly after the first few error responses, we can see a worrying message in logs:

ERROR 3042 --- [ctor-http-nio-5] io.netty.util.ResourceLeakDetector : LEAK: ByteBuf.release() was not called before it's garbage-collected. See http://netty.io/wiki/reference-counted-objects.html for more information.

Resource leak means that our service is going to crash. In minutes, hours or maybe days — it depends on other service errors count. The solution to this problem is straightforward: use the error response to generate an error message. Now it’s properly consumed.

The lesson learned: always test your application taking into consideration external service errors, especially under high traffic.

Issue 7 — unexpected code execution #

Reactor has a bunch of useful methods, helping writing expressive and declarative code. However, some of them may be a little bit tricky. Consider the following code:

String valueFromCache = "some non-empty value";

return Mono.justOrEmpty(valueFromCache)

.switchIfEmpty(Mono.just(getValueFromService()));

We used similar code to check the cache for a particular value and then call the external service if

the value was missing. The intention of the author seems to be clear: execute getValueFromService()

only in the case of lacking cache value. However, this code runs every time, even for cache hits.

The argument given to .switchIfEmpty() is not a lambda here — and Mono.just() causes direct execution of code

passed as an argument.

The obvious solution is to use Mono.fromSupplier() and pass conditional code as a lambda, as in the example below:

String valueFromCache = "some non-empty value";

return Mono.justOrEmpty(valueFromCache)

.switchIfEmpty(Mono.fromSupplier(() -> getValueFromService()));

The lesson learned: Reactor API has many different methods. Always consider whether the argument should be passed as is or wrapped with lambda.

Benefits from migration #

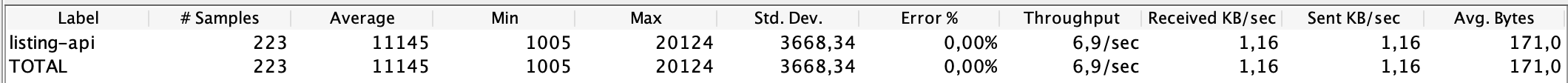

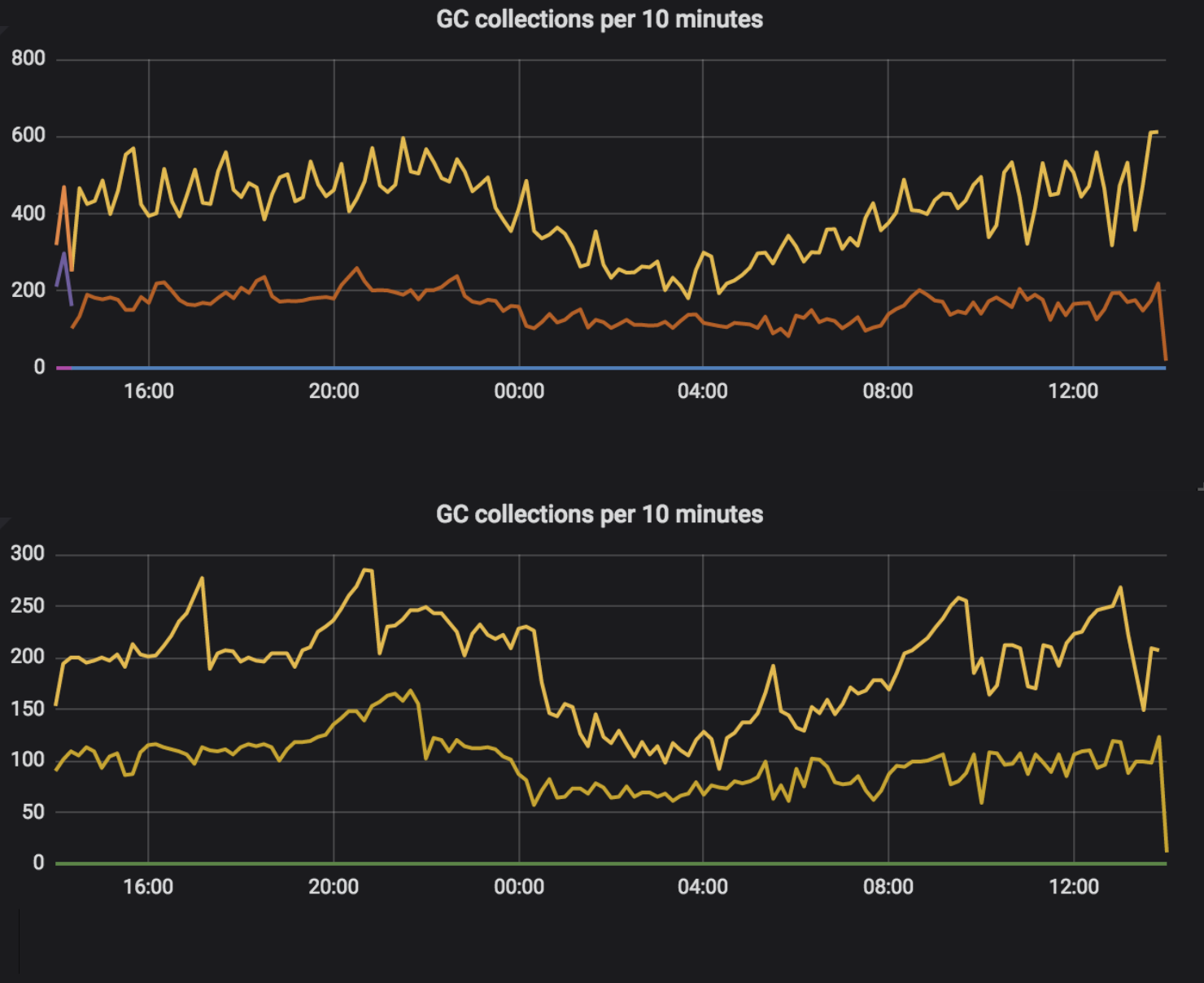

It’s time, to sum up, and check the production metrics of our service after migration to WebFlux. The obvious and direct effect is a decreased number of threads used by the application. Interesting is that we did not change application type to reactive (we still used servlets, see Stage 3 for details), but also utilization of Undertow worker threads became one order of magnitude smaller.

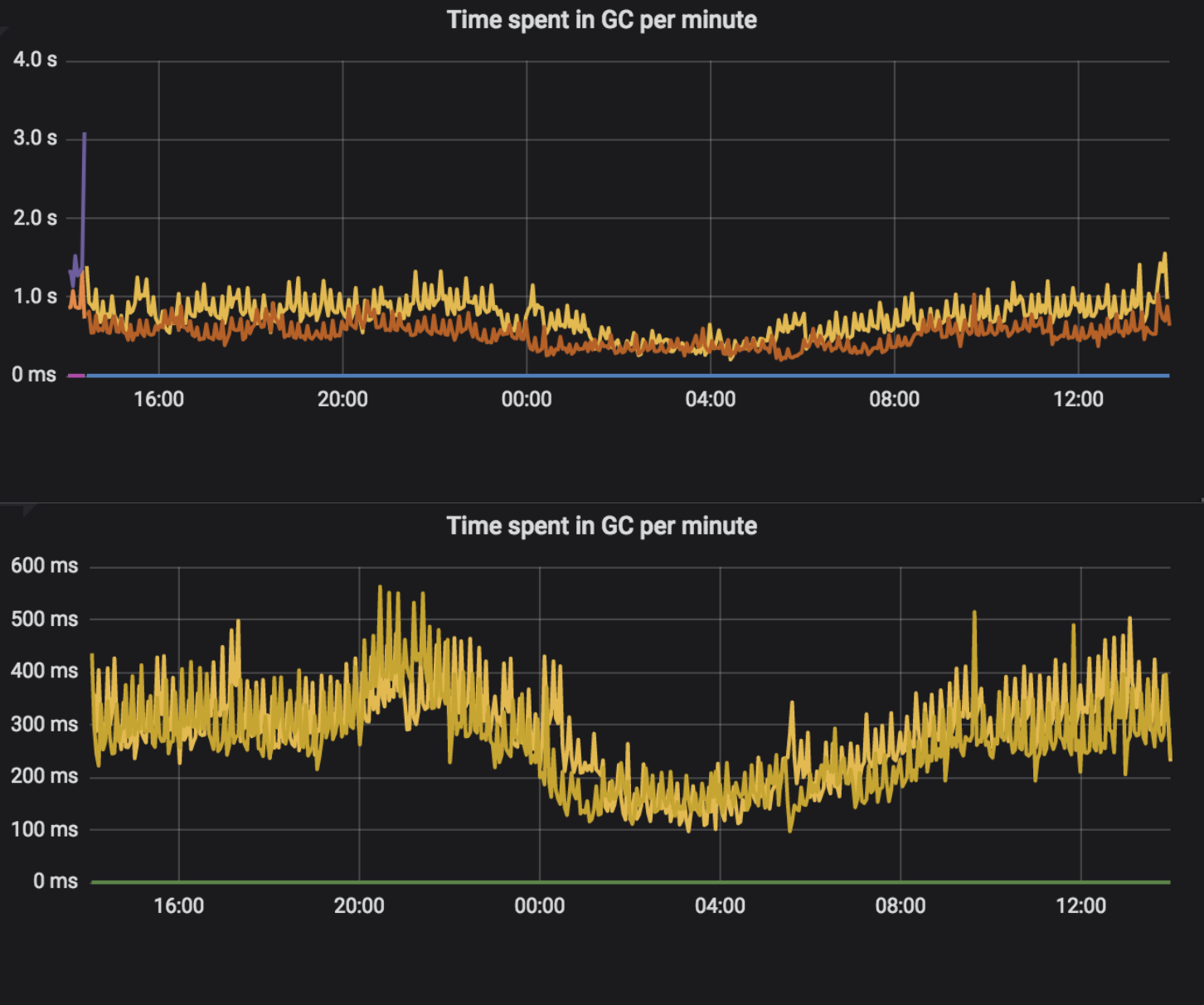

How were low-level metrics affected? We observed fewer garbage collections, and also they took less time. The upper part of each chart shows the blocking version, while the lower part shows the reactive version.

Also, the response time slightly decreased, although we did not expect such an effect. Other metrics, like CPU load, file descriptors usage and total memory consumed, did not change. Our service also does much more work, which is not associated with the communication. Migrating flow to reactive around HTTP clients and controllers is critical, but not significant in terms of resource usage. As I said in the beginning, the expected benefit of migration is more scalability and resilience for latencies. We are sure that we obtained this target.

Conclusions #

Are you working on a greenfield? It’s a great chance to get familiar with WebFlux or another reactive framework.

Are you migrating existing microservice? Take factors covered in the article into consideration, not only technical ones — check time and people capability to work with new solutions. Decide consciously without blind faith in technology hype.

Always test your application. Integration and performance test covering external call latencies and errors are crucial in the migration process. Remember that reactive thinking is different from the well-known blocking, imperative approach.

Have fun and build resilient microservices!