How to stub external services in integration tests

In my previous post, I shared a way to hide technical boilerplate and make REST API calls more expressive within your integration tests. To further improve your tests, you also need a strategy for handling integrations with the “outside world.”

In this follow-up article, we’ll dive into stubbing external services. You’ll learn how to set up these stubs without cluttering your test logic, ensuring the GIVEN section clearly shows which external services participate in a given scenario. By the end of this article, you’ll be able to handle complex integration cases with minimal technical noise.

Sample application #

As a case study, we’ll model a simplified product creation workflow. In this domain, a product is an entity that serves as the blueprint for an offer.

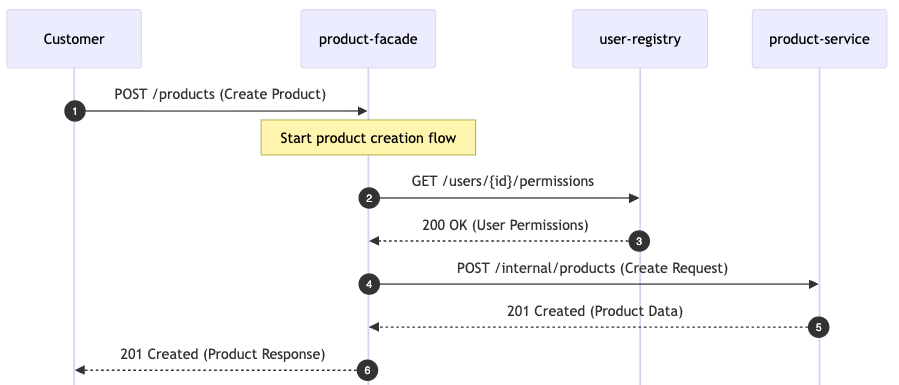

The process begins when a customer sends a REST call to the product-facade to initiate the creation of a new product.

Before proceeding, the product-facade verifies the user’s permissions by communicating with the user-registry.

Once verified, the product-facade calls the product-service to finalize the creation process.

How can we represent the integration with these services in our tests?

The classic approach #

Most integration tests rely on a centralized set of helper methods to handle stubs.

@Test

fun `should create a new product`() {

// given

stubUserPermissions(sampleUserId, sampleUserPermissionsResponse)

stubCreateProduct(sampleProductRequest, sampleProductResponse)

// when

val response = api()

.productCreation()

.createProduct(CreateProductApiFixture.productCreationDto)

// then

response.expectStatus().isCreated

.expectHeader()

.contentType(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

.expectBody(ProductCreationResponse::class.java)

.isEqualTo(ProductCreationResponse("sampleProductId"))

}

In this approach, technical details (Wiremock) are hidden behind methods starting with the stub prefix. Although common, this pattern has two significant issues:

-

Lack of Service Context: The method

stubUserPermissions(...)doesn’t explicitly state which service is being stubbed. As a result, we lose track of which external dependencies are involved in the test. While these connections are obvious on an architectural diagram, they become invisible in the code. This lack of clarity makes the test much harder to understand. -

Poor Developer Experience (DX): When all stubs are in one giant file and start with the same word

stub, finding the right one is difficult. For someone new to the project or the domain, this is a significant roadblock. Instead of the IDE helping you find what you need, you end up scrolling through a long list of methods, guessing which one is correct.

Refactor: grouping by service #

Usability issues and the lack of context can be addressed quite simply: by grouping methods into service-specific classes rather than one monolithic utility. This approach ensures that your tests immediately reveal which external systems are involved in the given business process.

@Test

fun `should create a new product`() {

// given

UserRegistry.stubUserPermissions(sampleUserId, sampleUserPermissionsResponse)

ProductService.stubCreateProduct(sampleProductRequest, sampleProductResponse)

// when

val response = api()

.productCreation()

.createProduct(CreateProductApiFixture.productCreationDto)

// then

response.expectStatus().isCreated

.expectHeader()

.contentType(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

.expectBody(ProductCreationResponse::class.java)

.isEqualTo(ProductCreationResponse("sampleProductId"))

}

While this approach is a step forward, it still has its drawbacks in the context of complex integration testing:

- Lack of a single entry point: When writing a test, there isn’t a single place to explore for all available stubs. You still have to know which specific classes exist to call them, which increases the overhead of writing new test cases.

- Technical method naming: Prefixing every method with

stubdescribes a technical action rather than the service’s actual behavior. In an integration test, the focus should be on describing expectations. Using a prefix likewillReturn...follows the same convention as WireMock itself, emphasizing expected behavior over technical setup. For instanceUserRegistryStub.willReturnUserPermissions(...)describes what the service does, not how it is stubbed.

Final solution: the stub builder pattern #

In our target solution, we use a single stub reference to stub any external service.

This reference acts as a central entry point, grouping information about all external dependencies our service communicates with.

To stub an external service, we use the following convention: stub.<externalService>().will<Action>().

@Test

fun `should create a new product`() {

// given

stub.userRegistry()

.forUser(sampleUserId)

.willReturnUserPermissions(sampleUserPermissionsResponse)

stub.productService().willCreateProduct(

request = sampleProductRequest,

response = sampleProductResponse

)

// when

val response = api()

.productCreation()

.createProduct(CreateProductApiFixture.productCreationDto)

// then

response.expectStatus().isCreated

.expectHeader()

.contentType(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

.expectBody(ProductCreationResponse::class.java)

.isEqualTo(ProductCreationResponse("sampleProductId"))

}

Under the hood, the stub reference is located in a base class inherited by all integration tests.

It aggregates all service stubs, providing easy access to them via functions.

You might wonder: why use functions instead of direct object references?

class BaseIntegrationTest {

@Autowired

lateinit var stub: ExternalServiceStubs

....

}

class ExternalServiceStubs(

private var objectMapper: ObjectMapper

) {

fun userRegistry() = UserRegistryStubBuilder(objectMapper)

fun productService() = ProductServiceStubBuilder(objectMapper)

}

The logic for stubbing specific service methods is encapsulated within <ExternalService>StubBuilder classes.

These builders come with a set of predefined default values that can be overridden using a fluent API.

This approach allows developers to specify only the minimum set of variables necessary for a particular test case.

Because one test might override a default parameter, we need to ensure that subsequent tests start with the same initial state.

To achieve this test isolation, each test creates these builder instances from scratch by calling the functions provided by the stub reference.

To give a better idea of how this works, here is a simplified implementation of the UserRegistryStubBuilder.

Notice how it hides the complexity of JSON serialization and WireMock-specific details.

class UserRegistryStubBuilder(

private val objectMapper: ObjectMapper

) {

private var userId: UserId = UserRegistryFixture.sampleUserId

private var statusCode: Int = HttpStatus.OK.value()

fun willReturnUserPermissions(

response: UserPermissionsDto

) {

WireMock.stubFor(

WireMock.get("/$userId/permissions")

.withHeader(HttpHeaders.ACCEPT, WireMock.equalTo(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON_VALUE)).willReturn(

WireMock.aResponse()

.withStatus(statusCode)

.withHeader(HttpHeaders.CONTENT_TYPE, MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON_VALUE)

.withBody(objectMapper.writeValueAsString(response))

)

)

}

fun forUser(userId: UserId) = apply {

this.userId = userId

}

fun willReturnError(code: Int) = apply {

this.statusCode = code

}

}

Summary #

Refactoring your stubs from monolithic helpers to the Stub Builder Pattern significantly improves the quality of your test suite.

Centralizing stubs under a single entry point allows your IDE to guide you through available options. No more guessing, just type stub and explore.

Thanks to the fluent API and sensible default values, you only define what truly matters for a specific scenario.

More importantly, this approach transforms your test suite into living documentation that clearly defines how your service interacts with the outside world.

Code examples #

The GitHub repository includes test implementations discussed in the article.