Dynamic Workload Balancing in Hermes

Hermes is a distributed publish-subscribe message broker that we use at Allegro to facilitate asynchronous communication between our microservices. As our usage of Hermes has grown over time, we faced a challenge in effectively distributing the load it handles to optimize resource utilization. In this blog post, we will present the implementation of a dynamic workload balancing algorithm that we developed to address this challenge. We will describe the approach we took, the lessons we learned along the way, and the results we achieved.

Hermes Architecture #

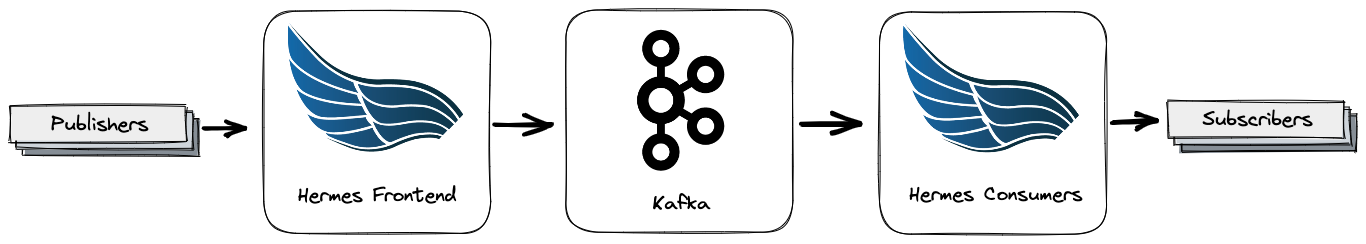

Before we delve deeper into the article’s topic, let’s first briefly introduce the architecture of Hermes, depicted in the diagram below:

As we can see, Hermes is composed of two main modules:

-

Hermes Frontend acts as a gateway, receiving messages from publishers via its REST interface, applying necessary preprocessing, and eventually storing them in Apache Kafka.

-

Hermes Consumers is a component that constitutes the delivery part of the system. Its role is to fetch messages from Kafka and push them to predefined subscribers while providing reliability mechanisms such as retries, backpressure, and rate limiting. For the sake of brevity, in the latter parts of the article, we’ll refer to a single instance of this module as a consumer.

Since the rest of this post discusses topics that mainly pertain to the delivery side of the system, let’s turn our attention to that now.

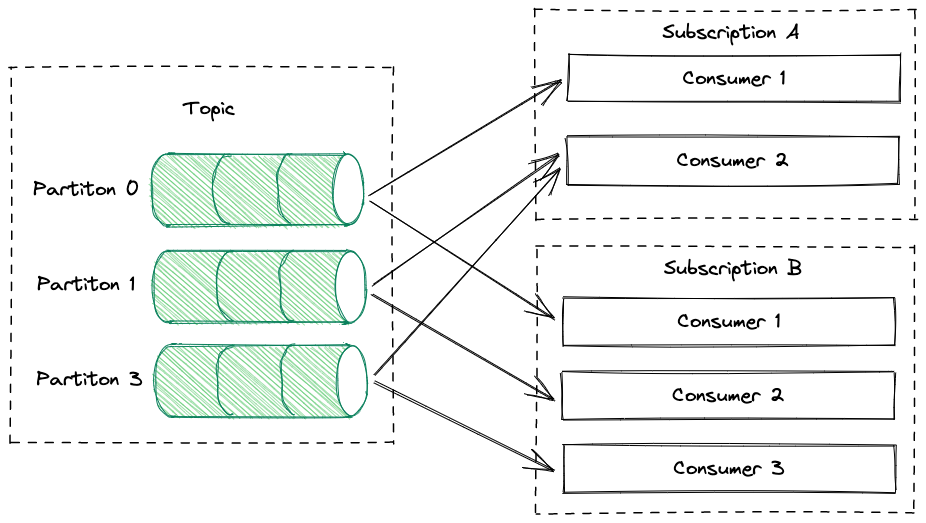

Apache Kafka organizes messages, also known as events, into topics. To facilitate parallelism, a topic usually has multiple partitions. Each event is stored in only one partition. When someone wants to receive messages from a given topic via Hermes, they create a new subscription with the defined HTTP endpoint to which messages will be delivered. Under the hood, Hermes assigns a group of consumers to that subscription, with each consumer handling at least one of the topic partitions. By default, a fixed number of consumers are assigned to a subscription, but the administrator can manually override this number on a per-subscription basis. It’s also worth noting that a single consumer can handle multiple subscriptions. The following diagram illustrates this:

Workload Balancer #

The Hermes Consumers module is designed to operate in highly dynamic environments, e.g. in the cloud, where new instances can be added, restarted, or removed at almost any time. This means that the module can handle these situations seamlessly and without disrupting the flow of messages. Additionally, it is horizontally scalable, meaning that when there is an increase in the number of subscriptions or an increase in outgoing traffic, we can easily scale out the cluster by adding new consumers. This adaptability to changing circumstances is achieved by a mechanism called the “workload balancer.” It acts as an arbiter, monitoring the state of the cluster, and if necessary, proposing appropriate adjustments in the distribution of subscriptions to the rest of the nodes.

Motivations for Improving Workload Balancer #

Our first implementation of the workload balancer aimed to always assign the same number of subscriptions to each consumer. This strategy is easy to understand and performs optimally when subscriptions are equal with respect to their load. However, this is not always the case. For example, imagine that we have two subscriptions. The first processes 1,000 messages per second, and the second only 10 messages per second. It is highly likely that they will not consume the same number of CPU cores, network bandwidth, etc. Thus, if we want to spread the load evenly, we should not assume that they are equal.

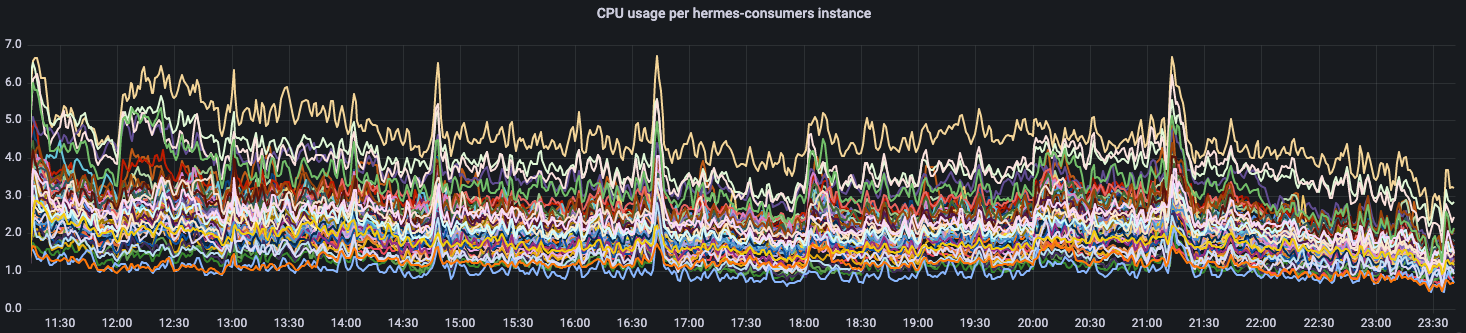

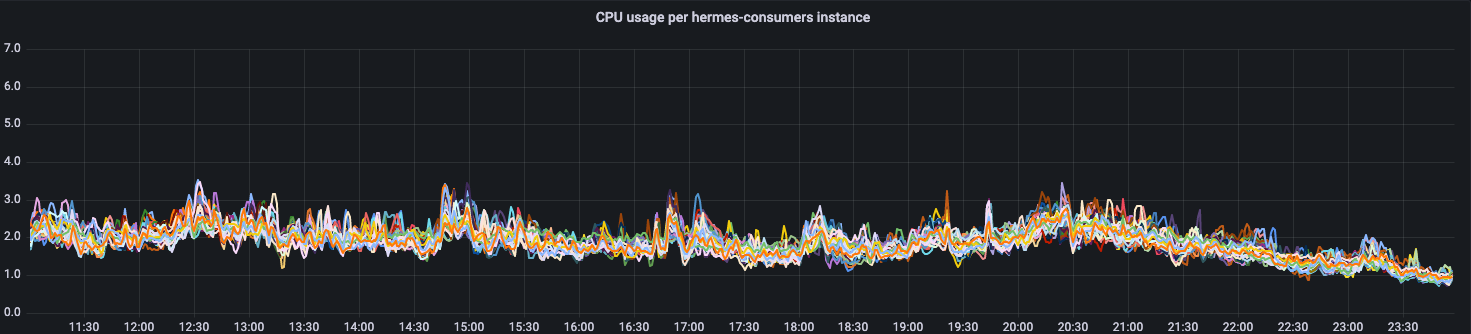

Usually, when we deploy our application in the cloud, we have to predefine the number of instances and the amount of resources (e.g. CPU, memory, etc.) that should be allocated to it. Unless we use a mechanism that adjusts these values on a per-instance basis, each instance will receive an equal share of the available resources. Now, let’s take a look at the CPU usage of each consumer from one of our Hermes production clusters using the workload balancer which does not account for the disproportions between subscriptions:

The figure below shows the difference in CPU usage between the least and most heavily loaded consumers:

Taking into account all of the above factors, in order not to compromise system performance, we always had to determine the right allocation based on the most loaded instance. Consequently, less busy instances were wasting resources as their demands were lower, not making the most of what was available. Knowing that our Hermes production clusters will continue to grow in terms of both traffic and the number of topics and subscriptions, we decided to develop a new and improved workload balancer, which we will discuss in the next section. We knew that if we didn’t do this, we would have to over-allocate even more resources in the future.

Solution #

Constraints and Requirements #

Before we proceed to the description of the solution we devised, we would like to discuss the requirements and constraints that guided our design process.

First, we wanted to preserve the core responsibilities of the original workload balancer, such as:

- Allocating work across newly added consumers

- Distributing work from removed consumers

- Assigning newly added subscriptions to available consumers

- Reclaiming resources previously assigned to removed subscriptions

Secondly, we decided not to change the existing rule of assigning the same number of subscriptions to each consumer. The reasoning behind this decision stemmed from the threading model implemented in Hermes Consumers, where every subscription assigned to a consumer is handled by a separate thread. Having an unequal number of threads between consumers could potentially lead to some consumers being overwhelmed with more context switches and a higher memory footprint.

Similarly, we wanted to preserve the strategy of determining the number of consumers a subscription should be assigned to (fixed and globally configured, but with the option of being overridden on a per-subscription basis by the administrator). Although it may not be optimal, for the reasons mentioned earlier, we chose to narrow down the scope of the improvements, keep it as is, and potentially revisit it in the future.

The last and very important factor that we had to consider while designing the new algorithm was the cost tied to every change in the assignment of subscriptions, particularly the cost of rebalancing Kafka’s consumer groups (i.e. temporarily suspending the delivery of messages from partitions affected by the rebalance until the process is completed).

With all of the above preconditions met, we were able to augment the capabilities of the workload balancer by making it aware of the heterogeneity of the subscriptions. We will discuss how we approached this in the following two subsections.

First Attempt #

As we mentioned earlier, the main reason for the imbalance was the fact that the original balancing algorithm was unaware of the differences between subscriptions. Therefore, in the first place, we wanted to make subscriptions comparable by associating with each of them an attribute called “weight.” Internally, it’s a vector of metrics characterizing a subscription. Currently, this vector has only one element, named “operations per second.” A single operation is an action executed by a consumer in the context of a given subscription, such as fetching an event from Kafka, committing offsets to Kafka, or sending an event to a subscriber. In the future, we may extend the weight vector by adding metrics that will allow us to eliminate uneven consumption of resources other than CPU.

Based on weights reported by individual consumers, a leader (one of the nodes from the Hermes Consumers cluster) builds subscription profiles, which are records containing information about subscriptions necessary for making balancing decisions. Among the details included in each profile are the weight and the timestamp of the last rebalance. It’s important to remember that a single subscription can be spanned across multiple consumers, resulting in multiple weight vectors associated with a single subscription. To resolve this, the leader builds a final weight vector (\(W\)), which is used in further calculations:

\begin{equation} W = \begin{bmatrix} max(m_{11},m_{12},\cdots,m_{1M}) & max(m_{21},m_{22},\cdots,m_{2M}) & \cdots & max(m_{N1},m_{N2},\cdots,m_{NM}) \end{bmatrix} \end{equation}

where:

\(m_{ij}\) is the value of metric \(i\) reported by consumer \(j\)

\(N\) is the number of metrics included in the weight vector

\(M\) is the number of consumers

It’s also worth noting that in order to smooth out abrupt changes and short-term fluctuations in traffic, we apply an exponentially weighted moving average (EWMA) to the collected metrics.

To address the requirement regarding the cost of reassigning subscriptions, we introduced a global parameter called “stabilization window.” After a subscription is assigned, the stabilization window determines the minimum time before the subscription can be reassigned. This “freezes” the subscription so that it doesn’t get reassigned too quickly, allowing the subscription to catch up with the events produced during the rebalancing process.

Equipped with the necessary terminology, we can now proceed to describe the algorithm itself. The high-level idea is fairly simple and boils down to the leader periodically executing the following steps:

- Fetch subscription weights from every consumer.

- Using information from the previous step, rebuild subscription profiles.

- Calculate the total weight of the whole Hermes Consumers cluster by summing all subscription weights.

- Determine the target consumer weight as an average of the weights of all consumers in the cluster.

- Build a set of consumers whose weights are above the average calculated in step 4.

- Build a set of consumers whose weights are below the average calculated in step 4.

- Swap subscriptions between the sets calculated in the previous two steps while maintaining the following restrictions:

- The weight of an instance from the overloaded set (step 5) is smaller than it was before the swap but is not smaller than the target value.

- The weight of an instance from the underloaded set (step 6) is greater than it was before the swap but is not greater than the target value.

- If, for a given subscription, the period of time since the last rebalance is shorter than the stabilization window, don’t consider the subscription eligible for the swap.

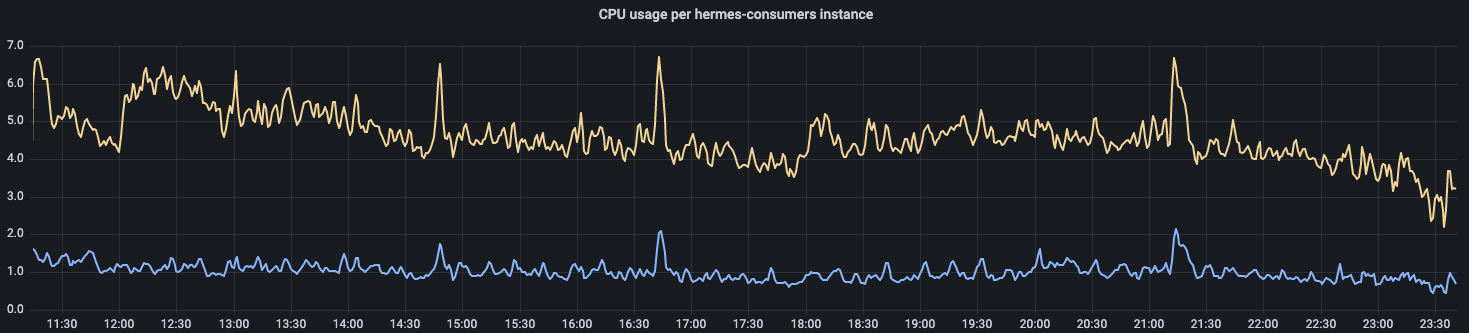

The graph below shows the results we obtained after deploying the implementation of this algorithm to production:

Although the graph shows that the new algorithm got us closer to having uniform utilization of CPU, we were not fully satisfied with that outcome. The reason for that is depicted below, where we compare the most loaded instance with the least loaded one. The degree of disparity in terms of CPU usage is still significant. Therefore, we decided to at least determine the reason for that state of affairs and, if possible, refine the algorithm.

While investigating this issue, we noticed a correlation between the class of hardware that consumers run on and their CPU usage. This observation led us to the conclusion that, despite the fact that load is evenly distributed, instances running on older generations of hardware utilize a higher percentage of available CPU power than those running on newer hardware, which is understandable as older machines are typically less performant. In the following section, we describe how we tackled this issue.

Second Attempt #

After our investigation, it was clear to us that if we wanted to achieve uniform CPU usage across the entire Hermes cluster, aiming for processing the same number of operations per second on each instance was not the way to go. This led us to the question of how to determine the ideal number of operations per second that each instance can handle without being either overloaded or underloaded. To answer this, we had to take into account the fact that in the cloud environment, it is not always possible to precisely define the hardware that our application will be running on. Potentially, we could put the burden of making the right decision on the Hermes administrator. However, this is a very tedious task and also hard to maintain in dynamic environments where applications are almost constantly moved around different physical machines.

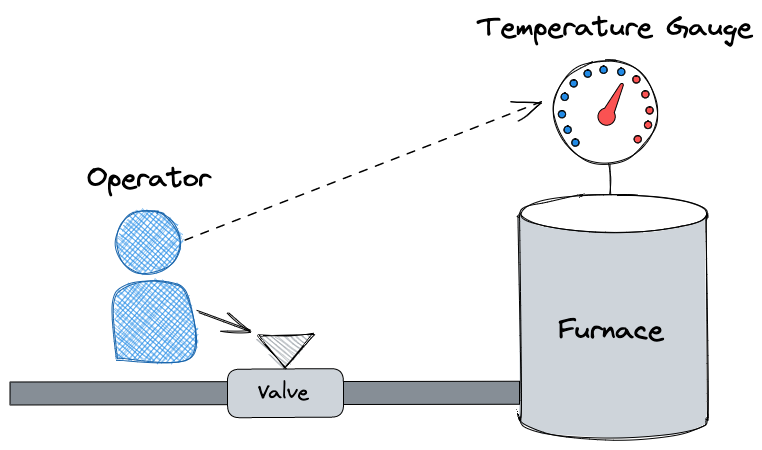

As we wanted to avoid any manual tuning, we decided to employ a concept well-known in Control Theory, called a proportional controller. To explain the idea behind this concept, let’s use an example. In the following picture, we see an operator who must adjust a hand valve to achieve the desired temperature in a furnace. The operator doesn’t know upfront what the appropriate degree to which the valve should be open is, therefore it is necessary to use a trial-and-error method to attain the desired outcome.

Now let’s take a look at how this example relates to Control Theory. Using Control Theory terms, we can say that the picture presents a feedback control system, also known as a closed-loop control system. In such systems, the current state and desired state of the system are referred to as the process variable and set point, respectively. In the example, the current temperature in the furnace represents the process variable, while the temperature that the operator wants to achieve is the set point. To fully automate the control system and eliminate the need for manual adjustments, we typically replace the operator with two components: an actuator and a controller. The controller calculates an error, which is the difference between the set point and the process variable. Based on the error, the controller proportionally increases or decreases its output (in this example, the degree to which the valve is open). The actuator uses the controller’s output to physically adjust the state of the system.

If we think about it, we realize that the problem a proportional controller solves is very similar to the one we encounter when we run Hermes on heterogeneous hardware. Specifically, our goal is to achieve equal CPU usage across all consumers, with the average usage of all consumers being our target. Additionally, we know that the number of operations per second processed by each consumer directly affects CPU usage. By utilizing a proportional controller, we can determine the value of this variable by calculating the error (the difference between the target and current CPU usage) and then adjusting the target weight accordingly. If we run the controller in a continuous loop, where it increases the target weight when current usage is below the target and vice versa, we should eventually reach the set point.

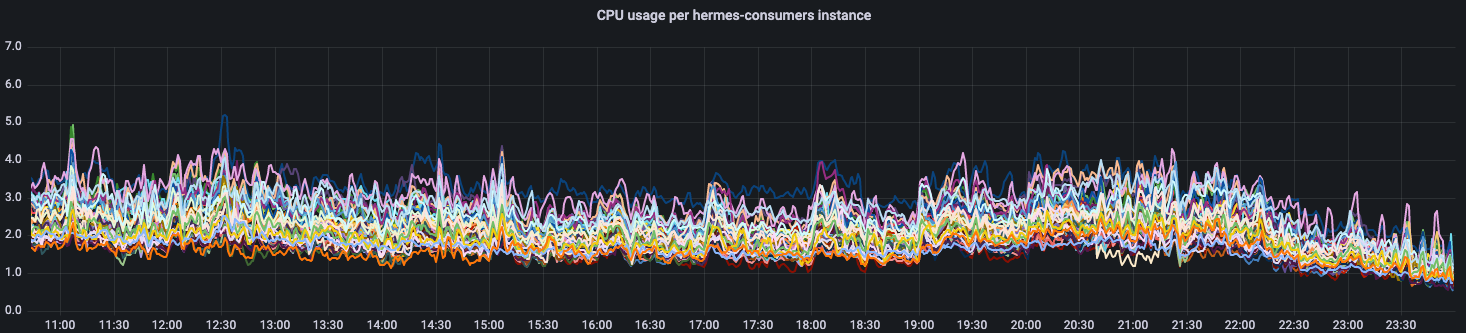

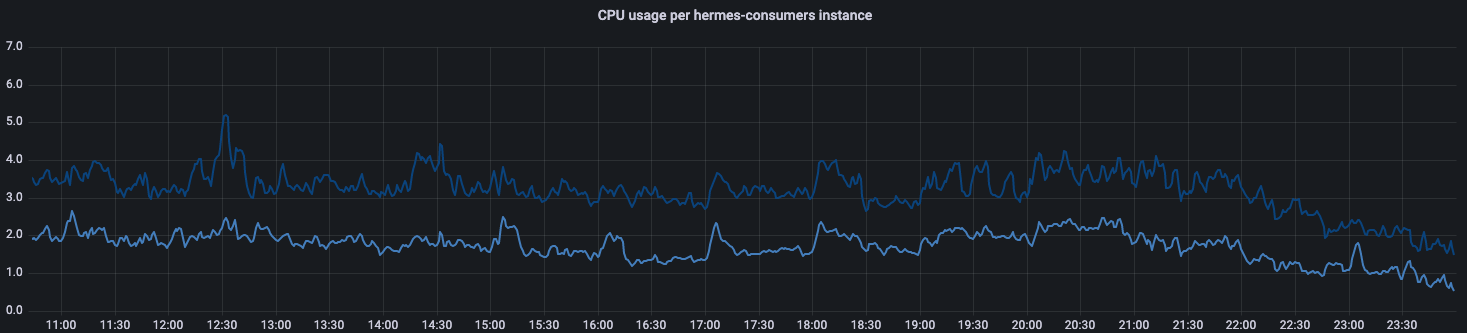

After integrating a proportional controller into our algorithm and deploying it to production, we were able to achieve the following results:

As we can see, the current CPU usage of all instances is very similar. This is exactly what we aimed for. If we assume that we are targeting 40% CPU utilization (to be able to handle additional traffic in case of a datacenter failover), by introducing the new algorithm we reduced the amount of allocated resources by approximately 42%.

Conclusion and Potential Improvements #

In this post, we have described the challenges we faced with balancing load in our Hermes clusters, and the steps we took to overcome them. By introducing our new workload balancing algorithm that dynamically adapts to varying subscription loads and heterogeneous hardware, we were able to achieve a more uniform distribution of CPU usage across Hermes Consumers instances.

This approach has allowed us to significantly reduce the amount of allocated resources and avoid performance issues caused by the imbalance that we observed earlier. However, there is still room for improvement. So far, we have been focused on optimizing CPU utilization, but the way the algorithm is designed, enables us to extend the spectrum of balanced resources in the future. For instance, we may consider factoring in memory and network bandwidth as well.

Additionally, we plan to improve the ease of operating Hermes clusters. We aim to avoid having tuning knobs and putting the burden of setting them correctly on the user. One such knob that we may want to remove in the future is the parameter defining how many consumers are assigned to a subscription. Currently, the Hermes administrator is responsible for choosing the value of this parameter for subscriptions where the default value is not a good fit. We suspect that this task could be automated by delegating it to the workload balancer.