Clean Architecture Story

The Clean Architecture concept has been around for some time and keeps surfacing in one place or another, yet it is not widely adopted. In this post I would like to introduce this topic in a less conventional way: starting with customer’s needs and going through various stages to present a solution that is clean enough to satisfy concepts from the aforementioned blog (or the book with the same name).

The perspective #

Why do we need software architecture? What is it anyway? An extensive definition can be found in a place a bit unexpected for an agile world — an enterprise-architecture definition from TOGAF:

- The fundamental concepts or properties of a system in its environment embodied in its elements, relationships, and in the principles of its design and evolution. (Source: ISO/IEC/IEEE 42010:2011)

- The structure of components, their inter-relationships, and the principles and guidelines governing their design and evolution over time.

And what do we need such a governing structure or shape for? Basically it allows us to make cost/time-efficient choices when it comes to development. And deployment. And operation. And maintenance.

It also allows us to keep as many options open as possible, so our future choices are not limited by an overcommitment from the past.

So — we have our perspective defined. Let’s dive into a real-world problem!

The challenge #

You are a young, promising programmer sitting in a dorm and one afternoon a stranger appears. “I run a small company that delivers packages from furniture shops to customers. I need a database that will allow reservation of slots. Is it something you are able to deliver?” “Of course!” — what else could a young, promising programmer answer?

The false start #

The customer needs a database, so what can we start with? The database schema, of course! We can identify entities with ease: a transport slot, a schedule, a user (we need some authentication, right?), a … something? Okay, perhaps it is not the easiest way. So why don’t we start with something else?

Let’s choose the technology to use! Let’s go with React frontend, Java+Spring backend, some SQL as persistence. To present a clickable version to our customer we need some warm-up work to set up an environment, create a deployable service version or GUI mockups, configure persistence and so on. In general: to pay attention to technical details — code necessary to set up something working, of which non-devs are usually not aware. It simply has to be done before we start talking about nitty-gritty for business logic.

The use-case-driven approach #

What if instead of starting with what we already know — how to visualize relationships, how to build a web-system — we started with what we didn’t know? Simply — by asking questions such as: How is the system going to be used? By whom?

Use cases #

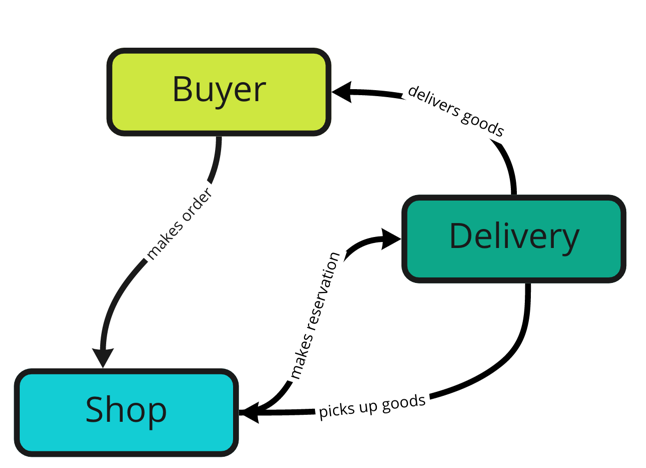

In other words — what are the use cases for the system? Let’s define the challenge once more using high-level actors

and interactions:  and pick the first

required interaction: shop makes a reservation. What is required to make a reservation? Hmm, I think that it would be

good to get the current schedule in the first place. Why am I using “get” instead of “display”? “Display” already

suggests a way of delivering output, when we hear “display” a computer screen comes to our minds, with a web

application. Single page web app, of course. “Get” is more neutral, it does not constrain our vision by a specific

presentation method. Frankly — is there anything wrong with delivering the current schedule over the phone, for

example?

and pick the first

required interaction: shop makes a reservation. What is required to make a reservation? Hmm, I think that it would be

good to get the current schedule in the first place. Why am I using “get” instead of “display”? “Display” already

suggests a way of delivering output, when we hear “display” a computer screen comes to our minds, with a web

application. Single page web app, of course. “Get” is more neutral, it does not constrain our vision by a specific

presentation method. Frankly — is there anything wrong with delivering the current schedule over the phone, for

example?

Getting the schedule #

So, we can start thinking about our schedule model — let it be a single instance representing a day with slots inside. Great, we have our entities! How to get one? Well, we need to check if there is already a stored schedule and if so — retrieve it from the repository. If the schedule is not available we have to create one. Based on…? Exactly — we do not know yet, all we can say is that it will probably be something flexible. Something to discuss with our customer — but this does not prevent us from going forward with our first use case. Logic is indeed simple:

fun getSchedule(scheduleDay: LocalDate): DaySchedule {

val daySchedule = daySchedulerRepository.get(scheduleDay)

if (daySchedule != null) {

return daySchedule

}

val newSchedule = dayScheduleCreator.create(scheduleDay)

return daySchedulerRepository.save(newSchedule)

}

(full commit: GitHub)

And even with this simple logic we identified a hidden assumption regarding the schedule definition: that there is a recipe for creating a daily schedule. What is more we can test retrieval of a schedule — with definition of schedule creator if required — without any irrelevant details, like database, UI, framework and so on. Test only business rules, without unnecessary details.

Reserving the slot #

To finish the reservation we have to add at least one more use case — one for reservation of a free slot. Provided that we re-use existing logic, the interaction is still simple:

fun reserve(slotId: SlotId): DaySchedule {

val daySchedule = getScheduleUseCase.getSchedule(scheduleDay = slotId.day)

val modifiedSchedule = daySchedule.reserveSlot(slotId.index)

return dayScheduleRepository.save(modifiedSchedule)

}

(full commit: GitHub)

And, as we can see — the slot reservation business rule (and constraint) is implemented at the domain model itself — so we are safe, that any other interaction, any other use case, is not going to break these rules. This approach also simplifies testing, as business rules can be verified in separation from the use case interaction logic.

Where is the “Clean Architecture”? #

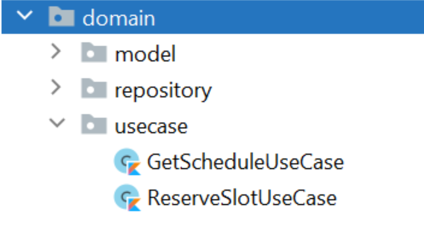

Let‘s stop with business logic for a moment. We created quite thoughtful, extensible code for sure, but why are we

talking about “Clean” architecture? We already used Domain-Driven Design and Hexagonal architecture concepts. Is there

anything more? Imagine that another person is going to help us with implementation. She is not aware of the source code

yet and simply would like to take a look at the codebase. And she sees:  It looks like something to her, doesn‘t it? A kind of reservation system! It is not yet another domain service with

some methods that have no clear connection with possible uses — the list of classes itself describes what the system

can do.

It looks like something to her, doesn‘t it? A kind of reservation system! It is not yet another domain service with

some methods that have no clear connection with possible uses — the list of classes itself describes what the system

can do.

The first assumption #

We have a mocked implementation as the schedule creator. It is OK to test logic at the unit test level, but not enough to run a prototype.

After a short call with our customer we know more about the daily schedule — there are six slots, two hours each, starting at 8:oo a.m. We also know that this recipe for the daily schedule is very, very simple and it is going to be changed soon (e.g. to accommodate for holidays, etc.). All these issues will be solved later, now we are at the prototype stage and our desired outcome is to have a working demo for our stranger.

Where to put this simple implementation of the schedule creator? So far, the domain used an interface for that. Are we going to put an implementation of this interface to the infrastructure package and treat it as something outside the domain? Certainly not! It is not complicated and this is part of the domain itself, we simply replace the mocked implementation of the schedule creator with class specification.

package eu.kowalcze.michal.arch.clean.example.domain.model

class DayScheduleCreator {

fun create(scheduleDay: LocalDate): DaySchedule = DaySchedule(

scheduleDay,

createStandardSlots()

)

//...

}

(full commit: GitHub)

The prototype #

I will not be original here — for the first prototype version the REST API sounds like something reasonable. Do we care about other infrastructure at the moment? Persistence? No! In the previous commits a map-based persistence layer is used for unit tests and this solution is good enough to start with. As long as the system is not restarted, of course.

What is important at this stage? We are introducing an API — this is a separate layer, so it is crucial to ensure that domain classes are not exposed to the outside world — and that we do not introduce a dependency on the API into the domain.

package eu.kowalcze.michal.arch.clean.example.api

@Controller

class GetScheduleEndpoint(private val getScheduleUseCase: GetScheduleUseCase) {

@GetMapping("/schedules/{localDate}")

fun getSchedules(@PathVariable localDate: String): DayScheduleDto {

val scheduleDay = LocalDate.parse(localDate)

val daySchedule = getScheduleUseCase.getSchedule(scheduleDay)

return daySchedule.toApi()

}

}

(full commit: GitHub)

The abstractions #

Use Case #

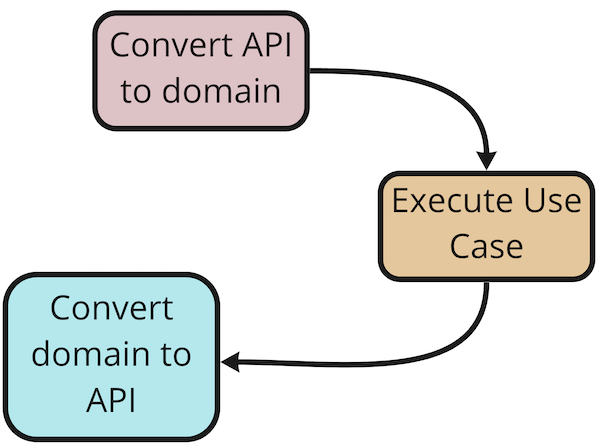

Checking the implementation of endpoints (see comments in the code) we can see that conceptually each endpoint executes

logic according to the same structure:  Well, why don’t we make some abstraction for this? Sounds like a crazy idea? Let‘s check! Based on our code and the

diagram above we can identify the

Well, why don’t we make some abstraction for this? Sounds like a crazy idea? Let‘s check! Based on our code and the

diagram above we can identify the UseCase abstraction — something that takes some input (domain input, to be precise)

and converts it to a (domain) output.

interface UseCase<INPUT, OUTPUT> {

fun apply(input: INPUT): OUTPUT

}

(full commit: GitHub)

Use Case Executor #

Great! We have use cases and I just realized that I would like to have an email in my inbox each time an exception is

thrown — and I do not want to depend on a spring-specific mechanism to do this. A common UseCaseExecutor will be a

great help to address this non-functional requirement.

class UseCaseExecutor(private val notificationGateway: NotificationGateway) {

fun <INPUT, OUTPUT> execute(useCase: UseCase<INPUT, OUTPUT>, input: INPUT): OUTPUT {

try {

return useCase.apply(input)

} catch (e: Exception) {

notificationGateway.notify(useCase, e)

throw e

}

}

}

(full commit: GitHub)

Framework-independent response #

In order to handle the next requirements in our plan we have to change the logic a bit — add the possibility of returning spring-specific response entities from the executor itself. To make our code reusable in a non-spring world (ktor, anyone?) we separated the plain executor from spring specific decorator, so that it is possible to use this code easily in other frameworks.

data class UseCaseApiResult<API_OUTPUT>(

val responseCode: Int,

val output: API_OUTPUT,

)

class SpringUseCaseExecutor(private val useCaseExecutor: UseCaseExecutor) {

fun <DOMAIN_INPUT, DOMAIN_OUTPUT, API_OUTPUT> execute(

useCase: UseCase<DOMAIN_INPUT, DOMAIN_OUTPUT>,

input: DOMAIN_INPUT,

toApiConversion: (domainOutput: DOMAIN_OUTPUT) -> UseCaseApiResult<API_OUTPUT>

): ResponseEntity<API_OUTPUT> {

return useCaseExecutor.execute(useCase, input, toApiConversion).toSpringResponse()

}

}

private fun <API_OUTPUT> UseCaseApiResult<API_OUTPUT>.toSpringResponse(): ResponseEntity<API_OUTPUT> =

ResponseEntity.status(responseCode).body(output)

(full commit: GitHub)

Handle domain exceptions #

Ooops. Our prototype is running and we observe exceptions resulting in HTTP 500 errors. It would be nice to convert these to dedicated response codes in a reasonable way yet without using much of spring infrastructure, for simplified maintenance (and possible future changes). This can be easily achieved by adding another parameter to use case execution, like this:

class UseCaseExecutor(private val notificationGateway: NotificationGateway) {

fun <DOMAIN_INPUT, DOMAIN_OUTPUT> execute(

useCase: UseCase<DOMAIN_INPUT, DOMAIN_OUTPUT>,

input: DOMAIN_INPUT,

toApiConversion: (domainOutput: DOMAIN_OUTPUT) -> UseCaseApiResult<*>,

handledExceptions: (ExceptionHandler.() -> Any)? = null,

): UseCaseApiResult<*> {

try {

val domainOutput = useCase.apply(input)

return toApiConversion(domainOutput)

} catch (e: Exception) {

// conceptual logic

val exceptionHandler = ExceptionHandler(e)

handledExceptions?.let { exceptionHandler.handledExceptions() }

return UseCaseApiResult(responseCodeIfExceptionIsHandled, exceptionHandler.message ?: e.message)

}

}

}

(full commit: GitHub)

Handle DTO conversion exceptions #

By simply replacing input with:

inputProvider: Any.() -> DOMAIN_INPUT,

(full commit: GitHub)

we are able to handle exceptions raised during creation of input domain objects in a uniform way, without any additional try/catches at the endpoint level.

The outcome #

What is the result of our journey across some functional requirements and a bit more non-functional requirements? By looking at the definition of an endpoint we have full documentation of its behaviour, including exceptions. Our code is easily portable to some different API (e.g. EJB), we have fully-auditable modifications, and we can exchange layers quite freely. Also analysis of whole service is simplified, as possible use cases are explicitely stated.

@PutMapping("/schedules/{localDate}/{index}", produces = ["application/json"], consumes = ["application/json"])

fun getSchedules(@PathVariable localDate: String, @PathVariable index: Int): ResponseEntity<*> =

useCaseExecutor.execute(

useCase = reserveSlotUseCase,

inputProvider = { SlotId(LocalDate.parse(localDate), index) },

toApiConversion = {

val dayScheduleDto = it.toApi()

UseCaseApiResult(HttpServletResponse.SC_ACCEPTED, dayScheduleDto)

},

handledExceptions = {

exception(InvalidSlotIndexException::class, UNPROCESSABLE_ENTITY, "INVALID-SLOT-ID")

exception(SlotAlreadyReservedException::class, CONFLICT, "SLOT-ALREADY-RESERVED")

},

)

(repository: GitHub)

A simple evaluation of our solution with measures mentioned at the beginning:

| Aspect | Evaluation | Has advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Development | UseCase abstraction forces unification of approach across different teams in a more significant way than standard service approach. |

✓ |

| Deployment | We did not consider deployment in our example. It certainly is not going to be different/harder than in case of hexagonal architecture. | |

| Operation | Use case-based approach reveals operation of the system, which reduces learning curve for both development and maintenance. | ✓ |

| Maintenance | Entry threshold might be lower compared to hexagonal approach, as service is separated horizontally (into layers) and vertically (into use cases with common domain model). | ✓ |

| Keeping options open | Similar to hexagonal architecture approach. |

TL;DR #

It is like hexagonal architecture with one additional dimension, composed of use cases, giving better insight into operations of a system and streamlining development and maintenance. Solution that was created during this narrative allows for creation of a self-documenting API endpoint.

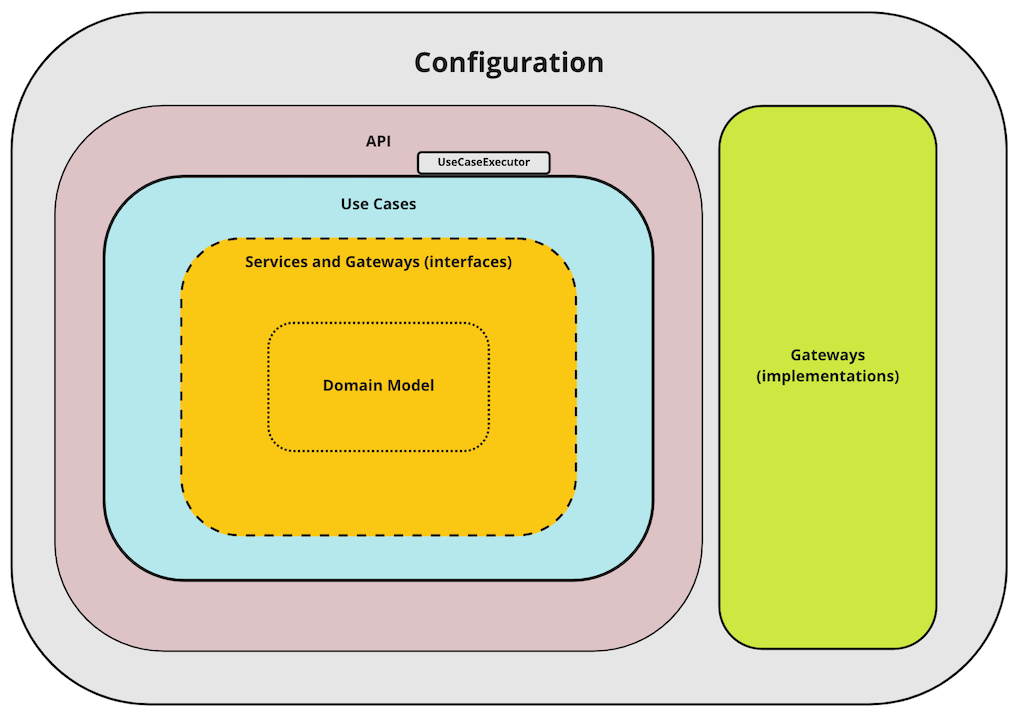

High-level overview #

With all this read we can switch our view to the high-level perspective:

and describe abstractions. Starting from the inside we have:

- Domain Model, Services and Gateways, which are responsible for defining business rules for the domain.

- UseCase, which orchestrates execution of business rules.

- UseCaseExecutor providing common behavior for all use cases.

- API connecting service with the outside world.

- Implementation of gateways, which connects with other services or persistence providers.

- Configuration, responsible for gluing all elements together.

I hope that you enjoy this simple story and find the concept of the Clean Architecture useful. Thank you for reading!