How we refactored the search form UI component

This article describes a classic case of refactoring a search form UI component, a critical part of every e-commerce platform. In it I’ll explain the precursor of change, analysis process, as well as aspects to pay attention to and principles to apply while designing a new solution. If you are planning to conduct refactoring of a codebase or just curious to learn more about frontend internals at Allegro, you might learn a thing or two from this article. Sounds interesting? Hop on!

How does the search form function at Allegro? #

For starters, so that we all are on the same page, let me briefly explain how the search form at Allegro works and what functionality it is responsible for. Under the hood, it is one of our many OpBox components and its technical name is opbox-search.

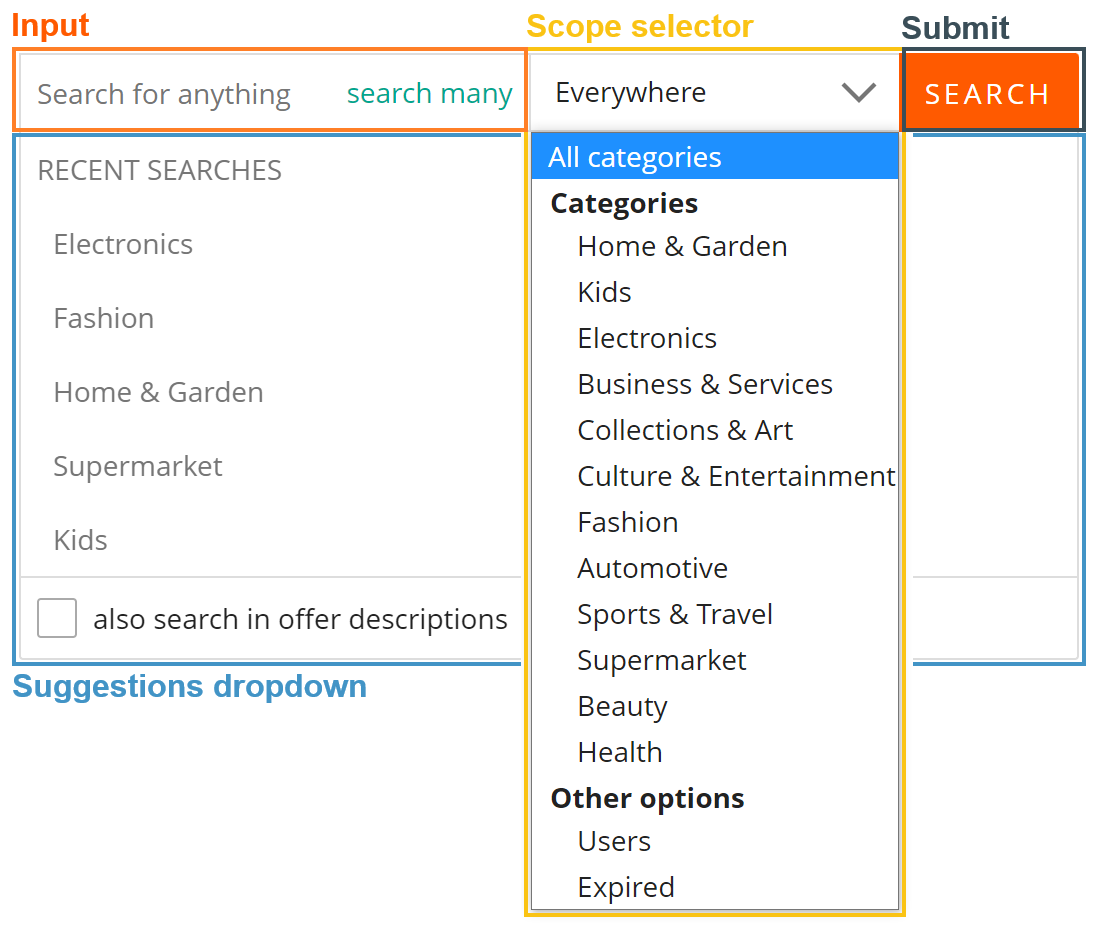

From UI standpoint it consists of four parts:

- an input field

- a scope selector

- a submit button

- a dropdown with a list of suggestions

Functionality-wise, whenever a user clicks/taps into the input or types a search phrase, a dropdown with a list of suggestions shows up and the user can navigate through by using keyboard/mouse/touchscreen. The suggestion list itself, at most, consists of two sections: phrases searched in the past and popular/matching suggestions. Those are fetched in real time as the user interacts with the form. Additionally, there is also a preconfigured option to search the phrase in products’ descriptions.

The form also provides a possibility to narrow down the search scope to a particular department, a certain user, a charity organization, etc. Depending on the selected scope, when user click the submission button, they are redirected to an appropriate product/user/charity listing page and the search phrase is sent as a URL query parameter.

At this point you might be wondering: this sounds quite easy, how come you messed up such a simple component?

A bit of history and the precursor of refactoring #

The initial commit took place back in 2017 and up until the point of refactoring the project, there were 2292 commits spread across 189 pull requests merged to the main branch. All those contributions were made by different independent teams. Over time the component evolved, some external APIs changed, some features became deprecated and new ones were added. At one point it also changed its ownership to another development team. As expected, all those factors left some marks on the codebase.

One of ample examples of troublesome conditions was the store entity that is responsible for handling the runtime state. In reality, besides performing its primary function it also handled network calls and contained pieces of business logic non-relevant for search scoping and suggestions listing.

To make matters worse, the internals of the entity were publicly exposed and therefore any dependent, e.g. the search input or the scope selector, was free to manipulate the store arbitrarily. Not hard to imagine, using such “shortcuts” has lead to degradation of codebase readability and maintainability.

At one point in time it reached its critical mass and we started considering the cost of maintaining the existing codebase vs. the cost of redeveloping it from scratch.

Refactoring expectations #

Refactoring itself doesn’t provide any business value. Instead it is an investment that should save engineers’ time and effort. That is why the primary goal was to gain back the confidence in further development of the component by:

- streamlining the maintenance of existing features

- streamlining and simplifying the development of new business features

- using tools, design patterns and principles to help engineers develop stable and correctly functioning features

Subsequently, achieving the goal would:

- shorten the delivery time

- create, from an architectural standpoint, a new solution resilient to multiple future contributions from different teams

Into the technical analysis #

So by this point we learned what the functional requirements are and identified the issues we have with the current solution. We also outlined refactoring expectations, hence we could start laying down the conceptual foundation of a new solution. We began by asking ourselves a few questions that could help us formalize our technical end goals.

What issues did we want to avoid this time? What did we want the new solution to improve upon? #

Going back to the store example, we clearly didn’t want to allow any dependent to mutate its data in any abritrary way nor did we want the store to contain pieces of logic that are not of its concern, e.g. networking. Instead we wanted to move these irrelevant pieces into more suitable locations, decrease entanglement of different parts of the codebase, structure it into logical entities that are more human readable, draw boundaries between those entities, define rules of communication and make sure we expose to the public API only what we intended to.

What development principles and design patterns could we have incorporated? #

The single-responsibility principle (SRP) #

The “S” of the “SOLID” acronym. As the name hints, a class (or a unit of code) should be responsible only for a single piece of functionality. A simple and powerful principle, yet quite often overlooked. Say, if we build a piece of logic associated with an input HTML element, its only responsibility should be to tightly interact with the element, e.g. listen to its DOM events and update its value if needed. At the same time, you don’t want this logic to affect the submission behavior of a form element inside of which the input element is placed.

The separation of concerns principle (SoC) #

SoC goes well in pair with SRP and states that one should not place functionalities of different domains under the same logical entity (say, an object, a class or a module). For example, we need to render a piece of information on the screen but beforehand the information needs to be fetched over the network. Since the view and network layers have different concerns we don’t want to place both of them under a single logical entity. Let these two be separate ones with established dependency relation to one another via a public API.

The loose coupling principle #

Loose coupling means that a single logical entity knows as little as possible about other entities and communication between them follows strict rules. One important characteristic we wanted to achieve here is to minimize negative effects on application’s runtime in case an entity malfunctions. As an analogy, we could imagine a graph of airports that are connected to each other via a set of flight routes. Say, there are direct routes from airport A to B, C and D. If the airport C gets closed due to renovation of a runway, the routes to B and D are not affected in any way. Moreover, some passengers might not even know that C is not operating at that moment.

Event-driven dataflow #

Since we are dealing with a UI component that has several moving parts, applying event-driven techniques come in handy because of their asynchronous nature and because messaging channels are subscription-based. Here is another analogy: you are at your place waiting for a hand-to-hand package delivery. Instead of opening the door every now and then to check if there is a courier behind it you would probably wait first for a doorbell to ring, right? Only once it rings (an event occurs), you would open the door to obtain the package.

Which development constraints (if any) did we want to introduce intentionally? #

We wanted the architecture of the new solution to follow a certain set of rules in order to maintain its structure. We also wanted to make it harder for engineers to break those rules. In the short term it might be a drawback, but we are interested in keeping the codebase well-maintained in the long run. By carefully designing the APIs and applying static type analysis we were not only able to meet the requirement but also lifted some complexity from engineers’ shoulders, and this is where TypeScript shines brightly.

Applying all of the above in a new store solution #

Based on the conclusions reached above we were ready to start the actual work and started it from the core, that is the store entity. As with any store solutions, let us list functional characteristics that one should provide.

The store should:

- hold current runtime state

- be initialized with a default state

- provide a public API that allows dependents to update its state during runtime in a controlled way

- expose information channels to propagate the state change to every subscriber

- not expose any implementation details

Defining the structure of the store’s data is as simple as declaring a TypeScript interface, but we need to be able to expose information that the state has mutated in a particular way. That is, we need to build event-driven communication between the store and its dependents. For this purpose we could use an event emitter and define as many topics as needed. In our case, having a dedicated topic per state property turned out to work perfectly as we didn’t have that many properties in the first place. And since we wanted to have the state and event emitter under the same umbrella, we encapsulated them into the following class declaration:

interface State {

foo: boolean;

bar: string;

// ...

}

type Topic = {

[K in Capitalize<keyof State>]: Uncapitalize<K>;

}

class Store {

constructor(

private state: State,

private readonly emitter: Emitter<Record<

keyof State,

(state: State) => void

>>,

) {}

public on(...args) { return this.emitter.on(...args);

}

The last piece of the puzzle is that we needed to automate event emission triggering. At the same time, we aimed to minimize the size of the boilerplate code needed to set up this behavior for each state property. Since every property has a corresponding topic, that is where we were able to leverage the power of JavaScript’s accessor descriptor and within a setter we could trigger the emission:

Object

.values(Topic)

.forEach(key => Object.defineProperty(Store.prototype, key, {

get() {

return this.state[key];

},

set(value) {

this.state = { ...this.state, [key]: value };

this.emitter.emit(key, this.state);

}

}));

After putting it all together, not only did we achieve the above-mentioned characteristics but also a simple way to work with the store:

store.foo = true;

store.on(Topic.Foo, (state: State) => ...);

At this point the store is ready and we would like to test how well the solution performs in reality.

Event-driven communication between the store and UI parts #

Now we could focus on developing the UI parts of our component. Luckily, business requirements provide enough hints where to place each piece of functionality. Let’s take a look at how we shaped the search input and the suggestion list, and how these UI parts cooperate with each other and the store.

Recall that functionality-wise the suggestion list is a dropdown that should be rendered whenever a user types a search phrase or clicks/taps into the input element. We also need to fetch best matching suggestions whenever the input value changes.

We started with the search input as it doesn’t have any dependencies besides the store. With functional requirements in mind, we aimed it to be good at doing just two things:

- Proxying DOM events such as focus, blur, click, keydown, etc.

- Notifying the store whenever the input value changes

Since updating the store is pretty much straightforward, let’s take a look at how we handled DOM events. Events such as

click, focus, blur convey the fact that there was some sort of interaction with the input HTML element. Unlike

input event, where one is interested in knowing what the current value is, the above-mentioned ones don’t include any

related information. We only need to be able to communicate to the dependents the fact that such an event took place

and that is why, similarly to the store, the search input has an event emitter of its own. Now, you might be thinking:

why would you want to have multiple sources of information given you already have the event-driven store solution? There

are a couple of reasons:

- Since those DOM events don’t contain additional information, there is nothing we need to put into our store. It aligns well with the single-responsibility principle, according to which the store only fulfills its primary function and has no hint of existence of the search input.

- By bypassing the store we shortened an event message travel distance from the source to a subscriber.

- It also aligns well with a mental model, where if one wants to react to an event that happened in the search input, one subscribes to its publicly available communication channels.

The gist of this approach and binding with the store can be achieved in just a few lines of code. Here we add several DOM event listeners and, depending on the event type, decide whether we need to proxy them into the event emitter or update the store’s state:

class SearchInput {

constructor(

private readonly inputNode: HTMLInputElement,

private store: Store,

public readonly emitter: Emitter<Record<

'click' | 'focus' | 'blur',

() => void,

>>,

) {

inputNode.addEventListener('click', () => emitter.emit('click'));

inputNode.addEventListener('focus', () => emitter.emit('focus'));

inputNode.addEventListener('blur', () => emitter.emit('blur'));

inputNode.addEventListener('input', ({ currentTarget: { value }}) => store.input = value);

}

// ...

}

Now, we can focus our attention on the suggestions list. Communication-wise, all it needs to do is to subscribe to several topics provided by the store and the search input:

import { fetchSuggestions } from './network';

class SuggestionsList {

constructor(

private store: Store,

private readonly searchInput: SearchInput,

// ...

) {

searchInput.emitter.on('click', () => this.renderVisible());

searchInput.emitter.on('focus', () => this.renderVisible());

searchInput.emitter.on('blur', () => this.renderHidden());

store.on('input', () => this.fetchItemsList());

store.on('suggestionsListData', () => {

this.renderItemsList();

this.renderVisible();

});

}

private async fetchItemsList() {

this.store.suggesiontsListData = await fetchSuggestions(this.store.input);

}

// ...

}

When a click or focus event message arrives from the search input, SuggestionsList renders a dropdown UI element.

On the other hand, blur event occurrence hides it. A change of input value in the store leads to fetching suggestions

over the network and lastly, whenever suggestions data is available, SuggestionsList renders the item list and makes

the dropdown visible.

Note that because we apply the separation of concerns principle, the fetchItemsList method only delegates a job to an

external dependency responsible for network communication. Upon successful response, SuggestionsList doesn’t

immediately start rendering the data, instead the data is put into the store and SuggestionList listens to that data

change. With such data circulation we ensure that:

- The store is a single source of truth (and data)

- Suggestions’ data is propagated to every dependent

- We avoid possible redundant rendering cycles

With that, our functional requirement is implemented.

The final solution #

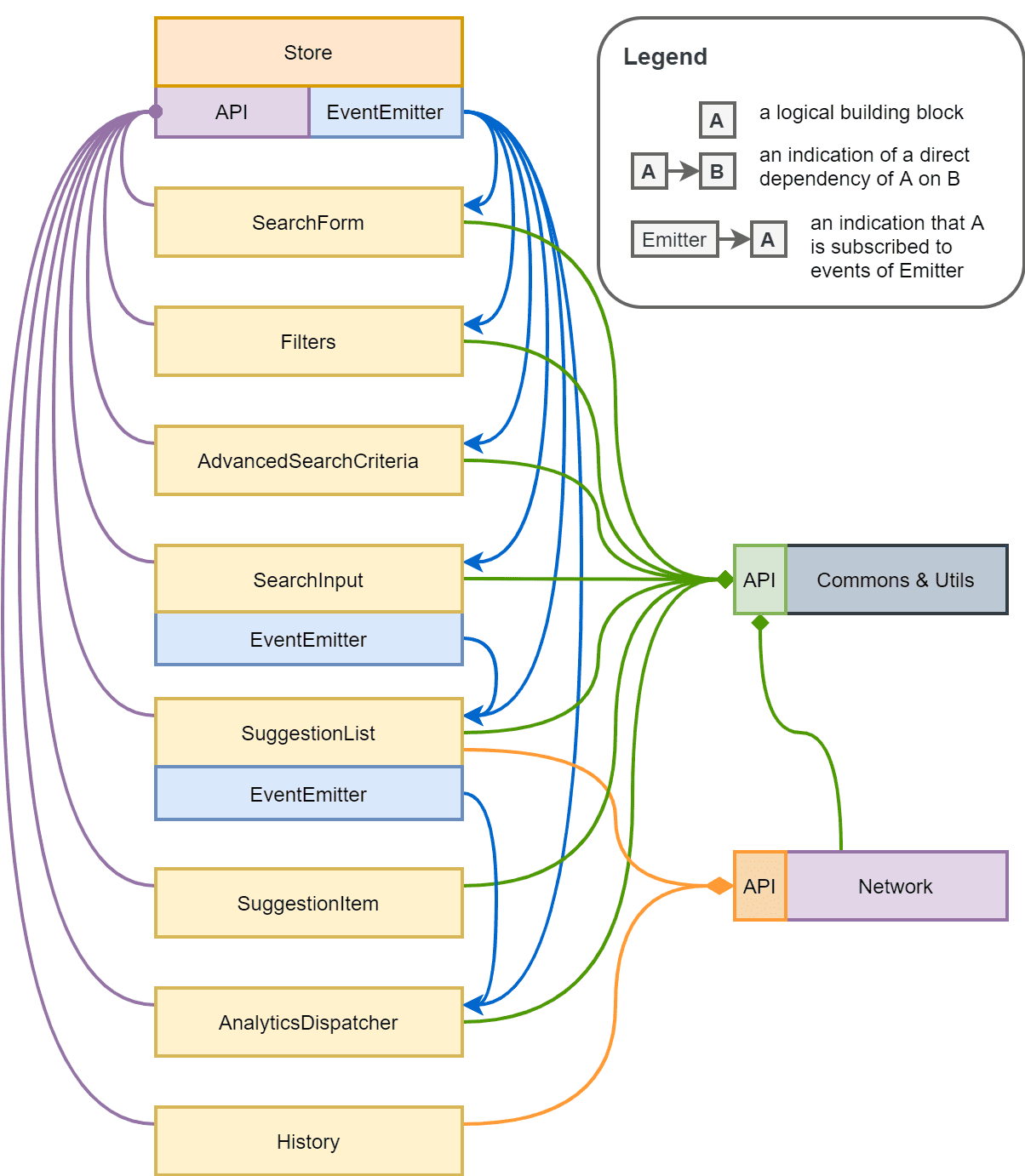

Reapplying the above principles and techniques to develop the remaining functional requirements, we ended up with a solution that can be illustrated as follows:

Were we able to meet our expectations? At the end of the day, after careful problem analysis, testing out POCs and development preparations, the implementation process itself went quite smoothly. Multiple people participated and we are quite satisfied with the end result. Will it withstand future challenges? Only time will tell.

Summary #

At Allegro we value our customer experience and that is why we pay a lot of attention to performance of our frontend solutions. At the same time, as software engineers, we want to stay productive and, therefore, we also care about our development experience. Achieving good results in both worlds is where the real challenge lies.