CSS Architecture and Performance in Micro Frontends

It’s been over 5 years since the introduction of the article describing the ongoing transformation of Allegro’s frontend architecture — an approach that was later formalized by the industry under the name of Micro Frontends. I think that after all this time we can safely say that this direction was correct and remained almost entirely unchanged in relation to the original idea. Still, some of the challenges foreseen in the publication soon became the reality. In this article I would like to focus on the CSS part of the whole adventure to tell you about how we manage consistency and frontend performance across over half a thousand components, and what it took us to get to where we stand today.

New Approach — New Challenges #

Handling all the dependencies, libraries and visual compatibility when the entire website resides in a single repository is a challenge by itself. The level of difficulty increases even more, when there are hundreds of said repositories, each managed by a different team and tooling. When in such situation, one of the things that quickly become apparent is the need for some kind of guidelines around the look of various aspects of components being developed like color scheme, spacing, fonts etc. — those are exactly the reasons why the Metrum Design System came to life.

In its initial form — apart from visual examples and design resources — Metrum was providing reusable PostCSS mixins that every developer could install via separate npm packages and include in the component they were working on.

@import 'node_modules/@metrum/button/css/mixins.css';

.button {

@mixin m-button;

background-color: black;

}

<button class="button"></button>

If we try to evaluate that approach we could come up with following pros and cons:

Pros

- Easy to use — install mixin and include in component’s selector;

- Mixins allow for sharing visual identity between components;

- Developers can use mixins in any version without depending on other parts of the page;

- Every component ships with a complete set of styles.

Cons

- Including mixins introduces duplication of CSS rules between components used on the same page;

- More files — every component brings at least one request for its styles;

- No sharing of CSS — no cache reuse between pages built from different components;

- Clashing of class names within the global namespace.

In summary, while being very flexible and easy to use, mixins-based approach was not ideal from a performance point of view. Every time when somebody wanted to use a button, input, link etc., they would have to include a mixin for it pulling the entire set of CSS rules to their stylesheet. This resulted in our users downloading unnecessary kilobytes during the first visit while bringing no caching benefit when navigating through other pages which in turn increased rendering times. We knew we could do better.

Enter CSS Modules #

After a lot of brainstorming, a decision was made that the next step should involve Metrum making use of CSS Modules. While the technical aspects and usage were changing as the adoption grew, the main principles stayed the same up to this day. Currently, whenever any developer wants to assemble a new component out of Metrum building blocks, they can install desired packages, compose styles from them and declare used classes in their markup:

.button {

composes: m-button from '@metrum/button';

composes: m-background-color-black from '@metrum/color';

}

import * as styles from './styles.css';

export default function render() {

return `

<button class="${styles.button}">...</button>

`;

}

Thanks to the fact that all of our micro frontends run on Node.js, this approach can be used quite easily with the majority of tooling available. The only thing left to do is to collect all of the required Metrum stylesheets during render in our facade server called opbox-web and embed them on the page with the correct order. Ordering requirement is important, because we follow atomic design and more complicated components (molecules, organisms) are built using simpler ones (atoms). Lets see what all of those changes did to our list of tradeoffs:

Pros

- Still easy to use — install package and compose desired classes in your component;

- Sharing classes means sharing visual traits which was one of our goals;

- Styles for certain module only appear once per page if used in multiple components;

- Each Metrum stylesheet can be cached by the browser separately and reused on different pages;

- Developers can still use packages in any version without depending on other parts of the page.

Cons

- Additional logic has to be maintained that extracts needed Metrum stylesheets from components and adds them to the page once;

- Above logic has to also take care of sorting so the order of styles is correct and we don’t run into problems with cascade;

- Multiple versions of the same Metrum component may be needed on the page;

- More and more requests have to be made as components transition to the new approach.

Judging from the upsides the transition was worth it: despite higher maintenance effort we were finally able to share common CSS code between components, the amount of downloaded data as well as render times started decreasing. Unfortunately, after some time we started to see a worrying trend related to the number of embedded stylesheets. Prior to this change, it was roughly equal to the number of components used on the page. Afterwards, with additional Metrum modules, plus the fact that multiple versions of them may be needed, we ended up with as much as around 100 requests for render-blocking CSS.

Usually, when we bring up the issue of excessive number of requests people respond with “So what? You have HTTP/2, right?” and yes, we do. It’s true that the user agent will reuse existing connections for multiple files but the limit of concurrent streams does exist, latency is still going to affect each one of them and the compression efficiency will be worse especially for those relatively small files like ours. We had to come up with yet another idea for improvement.

Let the Bundle Begin #

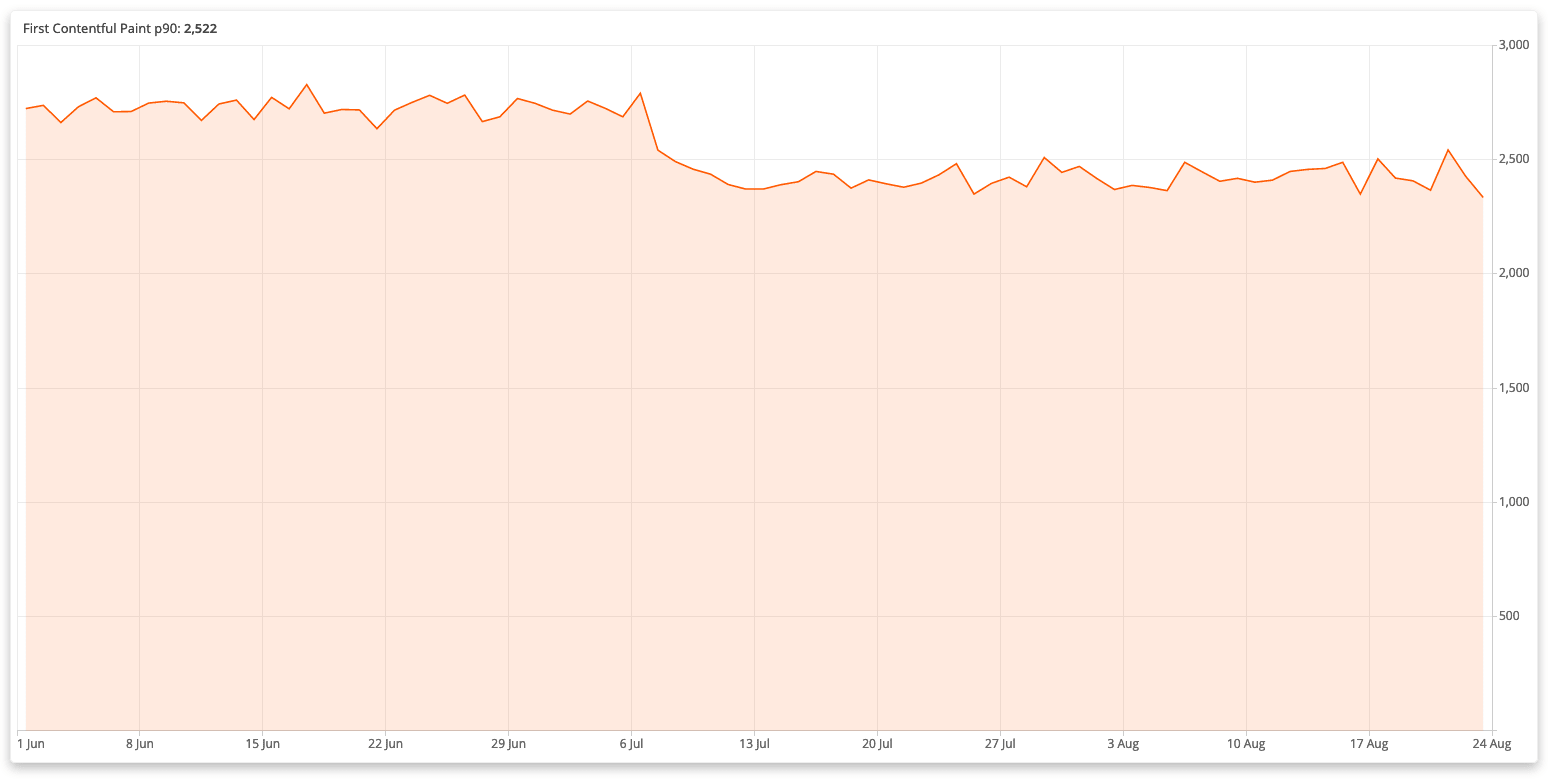

As I touched briefly earlier, we have the opbox-web — a place that’s already responsible for extracting, sorting and embedding Metrum dependencies. We figured that instead of adding each of them separately, we could prepare predefined bundles that would serve as replacements. We did as planned and, after deployment on 6th of July 2020, achieved 15% improvement in FCP metric time, which means that our users saw the first render of content faster by almost half a second.

Improvement was satisfactory, but it came at a certain cost. From that time on we had to make sure all of the components used on a certain page share the same versions of Metrum modules supported by the bundle and I assure you, it was bothersome to say the least. Monitoring that nobody updated their dependency by accident was one thing (especially that we managed to automate it) but undergoing a process of actually wanting to do this was another. In addition, every time we failed within that area we had to bail and serve every stylesheet separately, preventing incorrect order of CSS and bringing performance to the previous low.

Pros

- CSS Modules usage stayed the same;

- Fewer requests for critical resources resulted in noticeable improvement in FCP metric.

Cons

- Extra work is needed to keep Metrum packages versions aligned;

- Updating Metrum dependencies becomes much harder as it requires synchronization between all of the components on a certain page;

- All of the above meant that we only managed to enable this feature on the most popular of routes.

We knew there was going to be additional effort to maintain this solution but the performance gains outweighed the cost at that time. It took almost a year of tedious work from multiple teams to keep the look and feel of Allegro up to date with newest changes, until we came up with another idea.

Just In Time Bundling #

In the beginning of 2021 another idea started to form. This time we wanted to unlock the agile nature of our Micro Frontends and their deployment. We came to the conclusion that it would be ideal if instead of serving bundles containing a predefined list of components, we could send one composed of just the files that were actually required to render a certain page. Collecting the list of CSS that’s needed was not the problem — we were generating the HEAD section after all — but generating these unique bundles, well that was something different.

First option we had to verify was the possibility to prepare all of the bundles beforehand so they can be picked and served from CDN. Sadly, taking into account that there are around 500 components, any of which can either be used as a building block of a certain page or not, gives us 2500 combinations which is way more than we can handle. Even if we optimistically assumed that each stylesheet required around 50ms to generate, it would take us roughly 5x10141 years to cover everything. Additionally, it would not only be a waste of time and storage (some components have higher possibility to be used than others) but also at least a portion of the work would have to be redone every time a component is updated, what can happen multiple times a day.

Finally, we went with a different approach by implementing a bundler microservice. Its operating principle can be explained in a few steps:

- When user makes a request for a page, our server collects a list of CSS files that would normally be added to the HEAD section;

- It sends this list of files to our microservice asking for an URL to the corresponding bundle that contains them;

- The microservice checks if it has the bundle in its cache:

- If it does, then bundle URL is immediately returned;

- Otherwise, it also responds right away with empty result, triggering bundle generation in the background;

- Based on the response from the microservice, the server either embeds separate CSS files as usual or replaces them with a single bundle.

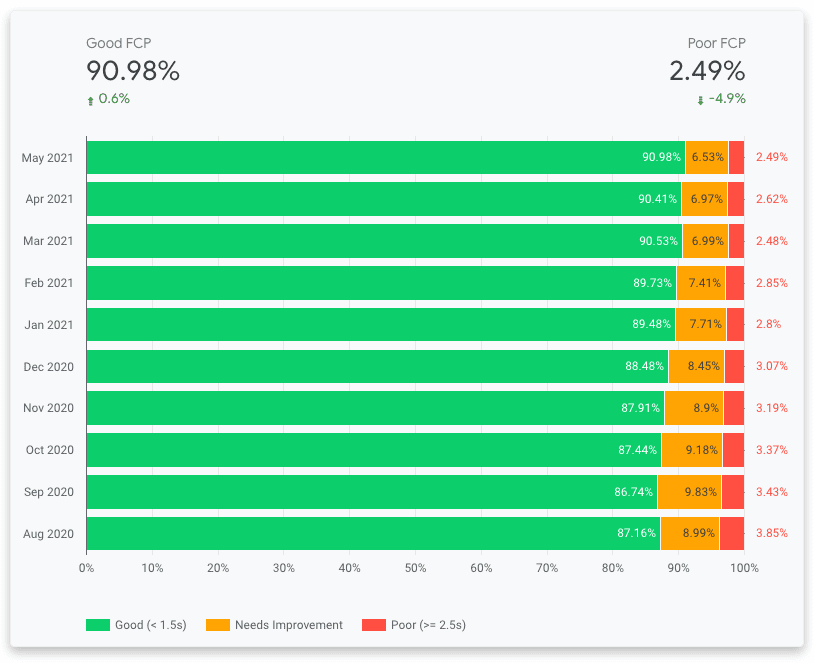

This is where we are now – generating only what is actually needed and keeping the duration overhead minimal. A lot of thought and multiple iterations went into making it possible, so I think you can expect a completely separate article about this microservice in the future. Most important thing for us is that the trend of constant improvement for our users continues as confirmed by Chrome UX Report:

Summary #

CSS architecture is one of the most important factors influencing performance, what makes ignoring it harder and harder as the page grows. Fortunately, our experience shows that even in higher-scale systems built using micro frontends, it is still possible to improve successfully. By solving problems of existing solutions and experimenting with new ideas we are able to constantly raise the bar of our metrics making browsing Allegro a better experience for our users month by month.