Testing React applications with Jest and Enzyme

JavaScript Frameworks play an important role in creating modern web applications. They provide developers with a variety of proven and well-tested solutions for creating efficient and scalable applications. Nowadays, it’s hard to find a company that builds its frontend products without using any framework, so knowing at least one of them is a necessary skill for every frontend developer. To truly know a framework, we need to understand not only how to create applications using it, but also how to test them.

JavaScript frameworks #

There are lots of JS frameworks for creating web applications, and every year there are more and more candidates to take the leading position. Currently, three frameworks play the main role: Angular, React and Vue. And in this article, I would like to focus on the most popular one - React.

To test or not to test #

When learning how to create applications using a given framework, developers often forget, or intentionally ignore, the necessity of testing already developed applications. As a result, you can often find complicated React applications with hundreds of components and zero or very few tests, which never ends well.

In my opinion, testing is so important because:

- for well-tested applications, the chances are great, that the developer will fix any bugs before pushing to the repository,

- having many well-written tests makes it easier for the developer to change the code, because he immediately knows if the application is still working properly,

- we can say that tests are also documentation - and what is even better, such a documentation is always up to date, because when code is changed and test fails we have to update this test.

While testing React components may seem complicated at first, the sooner we start learning the easier it will be to do it well over time and with little effort. In this post I would like to present one of the possibilities of testing React components.

React testing tools #

The set of frameworks and tools for testing React applications is very big, so at the beginning of the testing adventure the question is: what to choose? Instead of listing all the most popular tools, I would like to present those that I use every day, Jest + Enzyme.

Jest - One of the most popular (7M downloads each week) and very efficient JS testing framework, recommended by React creators.

Enzyme - React component testing tools. By adding an abstraction layer to the rendered component, Enzyme allows you to manipulate the component and search for other components and HTML elements within it. Another advantage is also well-written documentation that makes it easier to start working with this tool.

This combination of the test framework (Jest), and the component manipulation tool (Enzyme) enables the creation of efficient unit and integration tests for React components.

React components and how to test them #

Enough theory, let’s code!

I will start with a very basic component example together with tests. Later this component will be enriched with more advanced mechanisms (Router, Redux, Typescript) and I will present how to adjust tests, so that they still work and pass.

Basic component #

This is a simple React component example.

export const UserInfoBasic = ({ user }) => {

const [showDetails, setShowDetails] = useState(false);

const renderUserDetails = () => (

<div className={styles.details}>

<Typography variant="h5">Details</Typography>

<p>Login: {user.login}</p>

<p>Email: {user.email}</p>

<p>Age: {user.age}</p>

</div>

)

const getUserFullName = () => `${user.name} ${user.lastName}`;

const toggleDetails = () => setShowDetails(!showDetails);

return (

<Paper square={true} className={styles.paper}>

<Typography variant="h4">Info about user: {getUserFullName()}</Typography>

<p>First name: {user.name}</p>

<p>Last name: {user.lastName}</p>

<Button onClick={toggleDetails}>{showDetails ? 'Hide' : 'Show'} user details</Button>

{showDetails && renderUserDetails()}

</Paper>

);

};

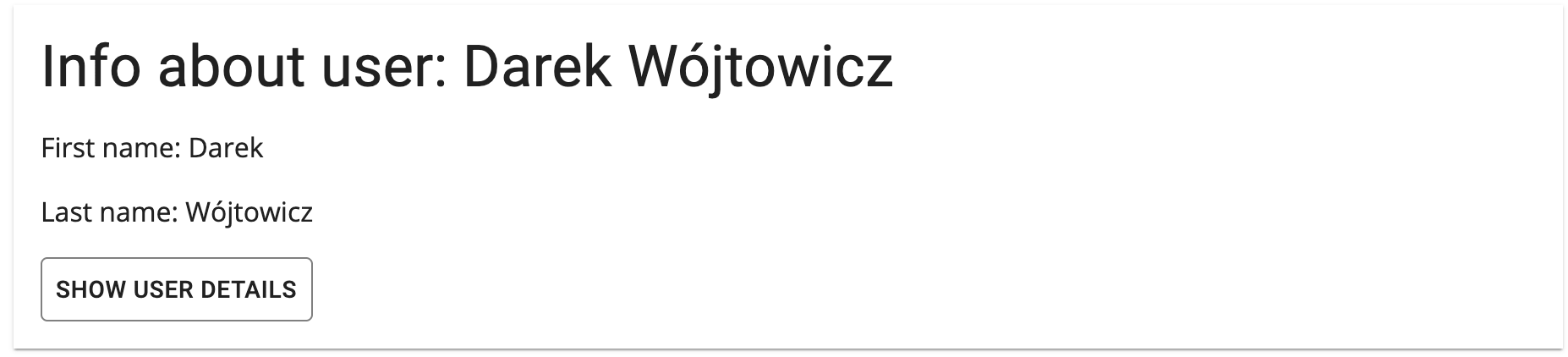

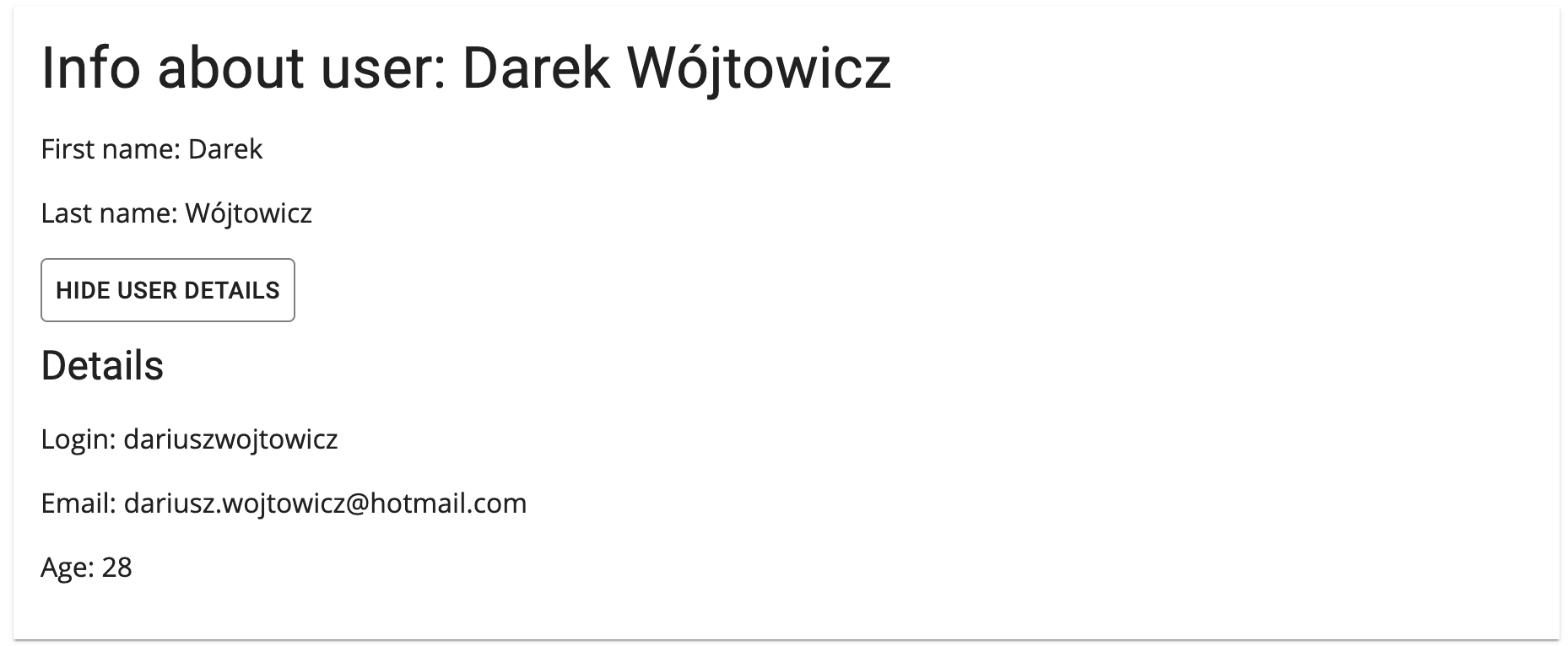

The role of UserInfoBasic is to present user data. Component receives a user object in props and displays user info in two sections. The first section contains the first and last name and is visible all the time. The second section provides details and is hidden after the first render, but can be viewed by clicking a button.

You can see what is rendered by this component initially and after button click on these screenshots.

This component does not use any advanced React mechanisms or external libraries. Tests of such a component written with Jest + Enzyme are very simple and intuitive.

const user = {

name: 'Darek',

lastName: 'Wojtowicz',

age: 28,

login: 'dariuszwojtowicz',

email: 'dar.wojtowicz@mail.com'

};

describe('UserInfoBasic', () => {

describe('Initial state', () => {

const wrapper = mount(

<UserInfoBasic user={user} />

);

test('should render header with full name', () => {

expect(wrapper.find(Typography).text()).toContain('Info about user: Darek Wojtowicz');

});

test('should not render details', () => {

expect(wrapper.findWhere((n) => n.text() === 'Login: dariuszwojtowicz').length).toEqual(0);

});

test('should render "show user details" button', () => {

expect(wrapper.find(Button).text()).toEqual('Show user details');

});

});

describe('After "Show user details" button click', () => {

const wrapper = mount(

<UserInfoBasic user={user} />

);

wrapper.find(Button).simulate('click');

test('should render details', () => {

expect(wrapper.findWhere((n) => n.text() === 'Login: dariuszwojtowicz').length).toEqual(1);

});

test('should render "Hide user details" button', () => {

expect(wrapper.find(Button).text()).toEqual('Hide user details');

});

});

});

First we define the user object, which we pass in the props of the tested component in all tests. Then we use the describe methods of the Jest framework to divide the tests into logical sets. In this case, two sets have been defined.

The first one, Initial state, is used to test the component in the initial state, without user interaction. The second one is for testing the component after clicking the Show user details button. Other Jest framework methods used here are the test method, which is used to write a single test, and the expect method, which checks if the condition we set is met.

In order to test a component, we need to have an instance of it, we need to render it somehow. This is where Enzyme comes in handy, which we can easily use to simulate creating and rendering a component. We can use one of the 3 methods (shallow, mount or render) to achieve this. In this example I use the mount function. The UserBasicInfo component was mounted using the mount method, with the user object that I defined earlier. This method returns an object, which can be used to check what was rendered and for interaction with the rendered component. This object is stored in a variable named wrapper.

Then on such an object we use the find method to check the content of the rendered component. In the first test, we check if the component has correctly rendered the user’s first and last name in the appropriate element. In the second test, we make sure that user details are not visible at first. And in the third, whether a button has been rendered to display user details.

In the second set of tests, we mount the component again and immediately afterwards, we use simulate method to simulate a user pressing the button.

As a result, the state of our component is now exactly as if the user had entered the page and clicked the button once. Then, in the first test, we check whether the user details are displayed. In the second test, we check whether the text on the button has changed from ‘Show user details’ to ‘Hide user details’.

More tests can be added, but for the purpose of showing the use of Jest + Enzyme for a simple component it is more than enough.

Component with Redux #

Complex projects written in React are very common. When an application consists not of several, but of dozens or even hundreds components, there is almost always a problem with managing the state. One solution is to use Redux, a predictable state container for JavaScript applications. In other words, Redux is an application data-flow architecture, because it maintains the state of an application in a single immutable tree object. This object can’t be changed directly, only using actions and reducers which create a new object.

Below you can see the implementation of the previous component adapted to work with Redux.

const mapStateToProps = state => ({ currentUser: state.currentUser });

const mapDispatchToProps = dispatch => ({ updateEmail: email => dispatch(updateEmail(email)) });

const UserInfoReduxComponent = ({ currentUser, updateEmail }) => {

const [showDetails, setShowDetails] = useState(false);

const renderUserDetails = () => (

<div className={styles.details}>

<Typography variant="h5">Details</Typography>

<p>Login: {currentUser.login}</p>

<p>Age: {currentUser.age}</p>

<TextField type="text" label="Email" value={currentUser.email} onChange={changeEmail} />

</div>

)

const getUserFullName = () => `${currentUser.name} ${currentUser.lastName}`;

const toggleDetails = () => setShowDetails(!showDetails);

const changeEmail = (event) => updateEmail(event.target.value);

return // Return statement hasn't changed

};

export const UserInfoRedux = connect(mapStateToProps, mapDispatchToProps)(UserInfoReduxComponent);

Only a few things have changed in comparision to the basic version of this component. New function mapStateToProps is responsible for mapping the Redux state to props of our component. The second function mapDispatchToProps is responsible for assigning Redux actions to component properties. With these actions the component is able to change the state managed by Redux (in this case the component can change the user’s email using the updateEmail action).

Instead of read-only text containing the user’s email address, an editable Textfield has appeared. Now, when email is changed, the updateEmail action is dispatched and email is changed in Redux store.

The last change in the component implementation is the use of the connect function from Redux, thanks to which our component is connected to global application state.

However, for the component to be able to work with Redux, we need to provide a Redux store in our application. And this is done as follows:

<Provider store={store}>

<App />

</Provider>

Now our component works with Redux, but our tests are unaware of this change. Running them ends up with the following error:

Error: Could not find "store" in the context of "Connect(UserInfoReduxComponent)".

This error means that we are trying to render a component with Enzyme that is now closely related to Redux, without providing any Redux context. The component has no access to the store.

Fortunately, the solution to this problem is very simple. The tests should be extended so that the component has access to the Redux Provider.

const user = {...};

const mockStore = configureStore([]);

const store = mockStore({

currentUser: user

});

const dispatchMock = () => Promise.resolve({});

store.dispatch = jest.fn(dispatchMock);

describe('UserInfoRedux', () => {

describe('After "Show user details" button click', () => {

const wrapper = mount(

<Provider store={store}>

<UserInfoRedux />

</Provider>,

{ context: { store } }

);

wrapper.find(Button).simulate('click');

test('should update user email in store after input value change', () => {

// when

wrapper.find('input').simulate('change', { target: { value: 'new@email.com' }});

// then

expect(store.dispatch).toHaveBeenCalledWith( {

email: "new@email.com",

type: "UPDATE_EMAIL"

});

});

});

});

We have the new mockStore function created with configureStore from the redux-mock-store package, which is used to create a mocked Redux Store containing user data in the currentUser field. Then we create a mock for the dispatch object, which is responsible for performing actions that change the Redux state.

The last step is to render the UserInfoRedux component inside the Redux Provider and pass our mocked store to the mount function.

Thanks to these changes, the tests pass again.

There is also one new test that simulates changing an email address and checks if the changes were performed on the Redux state. This way, we can test whether user interactions are reflected in the application state stored in Redux.

Component with Router #

Another solution often found in larger projects that really simplifies building applications is routing. React Router is responsible for routing in React applications. Thanks to it, we can, for example, use the same component at different addresses, in a slightly different way. As an example, I used the same component that displays user data. At the /profile address it displays the data of a currently logged user and allows to modify the email address. On the other hand, at the /users/{id} address the same component displays the user with given identifier, and it is read-only. Here are the changes in the component implementation that I made to achieve this result:

const mapStateToProps = state => ({

currentUser: state.currentUser,

users: state.users

});

const mapDispatchToProps = dispatch => ({ updateEmail: email => dispatch(updateEmail(email)) });

const UserInfoReduxRouterComponent = ({ currentUser, users, updateEmail, location, match }) => {

const [showDetails, setShowDetails] = useState(false);

const renderUserDetails = () => (

<div className={styles.details}>

<Typography variant="h5">Details</Typography>

<p>Login: {userData.login}</p>

<p>Age: {userData.age}</p>

<TextField

type="text"

label="Email"

value={userData.email}

onChange={changeEmail}

disabled={location.pathname !== '/profile'}

/>

</div>

);

const getUserFullName = () => `${userData.name} ${userData.lastName}`;

const toggleDetails = () => setShowDetails(!showDetails);

const changeEmail = (event) => {

if (location.pathname === '/profile') {

updateEmail(event.target.value);

}

};

const getUserData = () => {

if (location.pathname === '/profile') {

return currentUser;

} else {

const foundUser = users.find((user) => user.id == match.params.id);

if (foundUser) {

return foundUser;

}

}

return null;

};

const userData = getUserData();

const renderUserInfo = () => (

<>

<Typography variant="h4">Info about user: {getUserFullName()} (id: {userData.id})</Typography>

<p>First name: {userData.name}</p>

<p>Last name: {userData.lastName}</p>

<Button style={{'border': '1px solid grey'}} onClick={toggleDetails}>{showDetails ? 'Hide' : 'Show'} user details</Button>

{showDetails && renderUserDetails()}

</>

);

return (

<Paper square={true} className={styles.paper}>

{userData && renderUserInfo()}

{!userData && <h3>User with given id does not exist</h3>}

</Paper>

);

};

export const UserInfoReduxRouter = connect(mapStateToProps, mapDispatchToProps)(UserInfoReduxRouterComponent);

So what has changed? There is the new users property that comes from Redux store. This prop is the list of all existing users. There is the new disabled property on the email field. With this property, email is editable only at the /profile address. The most important thing is how we define the userData variable because this variable is the source of information for rendering user data. First, we define userData as null. If the current pathname is /profile then we assign a currently logged user to userData. If the address is different, it means that we are on the /users/{id} page. In this case, we search for a user with a given identifier in a list of all users. So there are three possible results:

- current user data is rendered at the /profile page,

- a user with a given id is rendered at the /users/{id} page,

- text “User with given id does not exist” is rendered if there is no user with a given id on the list.

We need one more change if we want our component to work under both addresses. We have to render this component inside BrowserRouter component, that comes from React Router, like this:

<BrowserRouter>

<Switch>

<Route exact path="/profile" component={UserInfoReduxRouter} />

<Route exact path="/users/:id" component={UserInfoReduxRouter} />

</Switch>

</BrowserRouter>

The above code defines the routing of the application using the BrowserRouter component. We tell the router which component should be loaded for a given address. That’s all.

Unfortunately, the tests stopped working again, and here’s the error we get after running them:

Error: Uncaught [TypeError: Cannot read property 'pathname' of undefined]

This error means that during the test execution, the component does not have access to the location object from which the pathname attribute is retrieved. As mentioned above, this object is provided by React Router at runtime. In tests, however, we have to provide it differently. Here’s the snippet of the test code that is responsible for it:

const path = `/profile`;

const match = {

isExact: true,

path,

url: path

};

const location = createLocation(match.url);

const store = getStore();

const wrapper = mount(

<Provider store={store}>

<UserInfoReduxRouter

match={match}

location={location}

/>

</Provider>,

{ context: { store } }

);

First, we define the address at which we want to test our component. Next, we create a mock for the match object and pass the address to it (the path variable). Using the createLocation function that comes from the history package, we create a mock for the location object. Finally, we pass the created mocks of match and location objects to the component props. Thanks to these changes, we provided the routing context and the component can work properly. Tests pass again.

Component with TypeScript #

The last tool I would like to mention is the TypeScript language. Imagine a huge React project with 20 developers and hundreds of components. Each component accepts several props. Such a project written in JS, without typing, would be very difficult to maintain. Programmers have to guess variable types. Is it, a string? or maybe a number? What fields must be defined in the user property for the component to work properly? That is why TypeScript was created, it is a language that is a superset of JavaScript, and it introduces static type checking. Looking at the implementation of the component above, we can see what props the component takes. This is, for example, currentUser, but we do not know what properties should such object provide. Is email required? Can we skip age? TypeScript solves this kind of issues.

Typescript also makes writing and maintaining tests easier, because:

- we don’t have to look at the component implementation every few seconds just to verify its API thanks to static types,

- when some public interface is changed and it was previously used in some test, we don’t need to run the tests to know which of them fails - they just won’t compile,

- we do not need to write test cases where we are passing wrong types to tested function or component - Typescript makes sure that there are no such situations in code.

Now let’s see how our component looks like, written in TypeScript.

First, we define the interface that describes a user:

export interface User {

id: number;

name: string;

lastName: string;

login: string;

email: string;

age?: number;

}

The interface clearly defines which fields describe a user object and which fields are not required. In this case, the age field is optional.

Here is the use of TypeScript in the component itself:

const mapStateToProps = (state: { currentUser: User; users: User[]; }) => ({

currentUser: state.currentUser,

users: state.users

});

const mapDispatchToProps = (dispatch: Dispatch) => ({ updateEmail: (email: string) => dispatch(updateEmail(email)) });

export interface UserInfoReduxRouterTsProps {

currentUser: User;

users: User[];

updateEmail: (email: string) => UpdateEmailAction;

location: Location;

}

const UserInfoReduxRouterTsComponent: React.FC<UserInfoReduxRouterTsProps> = (

{ currentUser, users, updateEmail, location }

) => {

const [showDetails, setShowDetails] = useState(false);

const renderUserDetails = (): JSX.Element => (

<div className={styles.details}>

<Typography variant="h5">Details</Typography>

<p>Login: {userData.login}</p>

<p>Age: {userData.age}</p>

<TextField

fullWidth

type="text"

label="Email"

value={userData.email}

onChange={changeEmail}

disabled={location.pathname !== '/profile'}

/>

</div>

);

const getUserFullName = (): JSX.Element => `${userData.name} ${userData.lastName}`;

const toggleDetails = (): void => setShowDetails(!showDetails);

const changeEmail = (event: React.ChangeEvent<any>): void => {

if (location.pathname === '/profile') {

updateEmail(event.target.value);

}

}

const getUserId = (): number => parseInt(location.pathname.split('users/')[1], 10);

const getUserData = (): User => {

if (location.pathname === '/profile') {

return currentUser;

} else {

const foundUser = users.find((user: User) => user.id == getUserId());

if (foundUser) {

return foundUser;

}

}

return null;

};

const userData: User = getUserData();

// No more changes, rest is the same.

};

export const UserInfoReduxRouterTs = withRouter(connect(mapStateToProps, mapDispatchToProps)(UserInfoReduxRouterTsComponent));

The component has changed a lot. The most important thing is the definition of the UserInfoReduxRouterTsProps interface, which describes what props the component takes, which are optional and what types they have. As a result, the programmer who wants to use such a component knows immediately what to pass to it. Other changes are the appearance of types for parameters in functions as well as functions return types. Both are very helpful for future changes in component or code refactoring.

After these changes tests stopped working again. The error is:

Type 'Location<{}>' is missing the following properties from type 'Location': ancestorOrigins, host, hostname, hef, and 6 more.

So far in tests, we passed the mocked location object directly as component props. Now TypeScript detects that the type of passed location object is not identical to the type expected by the component. To fix this issue we can simply simulate a context similar to the one in which the component lives while the application is running. To do this, we have to embed the component in the context of the router. With this change the location parameter comes from Router, and it has exactly the type that the components expect.

const path = `/profile`;

const store = getStore();

const wrapper = mount(

<MemoryRouter initialEntries={[path]}>

<Provider store={store}>

<UserInfoReduxRouterTs />

</Provider>

</MemoryRouter>,

{ context: { store } }

);

The MemoryRouter component is imported from the ‘react-router’ package. We define a variable path to simulate the behavior of the component at a specific address (here /profile). Then, we mount our component wrapped in MemoryRouter, and pass the previously defined path as prop.

Thanks to these changes, the tests pass again.

Conclusion #

As I mentioned at the beginning, it’s hard to find frontend applications that are created without the use of frameworks these days. As can be seen in this text, it is also difficult to create complex projects without introducing additional libraries like Router, Redux or TypeScript. You can also observe that including them to the project requires some changes to the tests as well. However, if we take tests seriously from the very beginning of application development, and we create them regularly, we can quickly and efficiently adapt them to changes in the application.

But would it be easy if we wrote tests after the application is already developed and uses all these extensions? Probably not, often if we do not start testing the application from the beginning, then the cost of introducing the tests is so high, that we decide to give them up, and our application loses a lot of value, because without tests it is difficult to maintain the app and introduce further changes.

So, I encourage you to test!

If you are interested in the implementation details take a look at the testing-react-components github repository.