Distributed rate limiting of delivery attempts

In our services ecosystem it’s usually the case that services can handle a limited amount of requests per second. We show how we introduced a new algorithm for our publish-subscribe queue system. The road to production deployment highlights some key distributed systems’ takeaways we’d like to discuss.

Rate limiting #

Rate of requests is definitely not the only limitation we impose on our systems, but with confidence we might say it’s the first one that comes to mind when considering input data. Among others, we might find throughput (kb/s) or the size of individual requests.

We are going to focus on limiting the rate of requests to a service from the perspective of a publish–subscribe message broker. In our case it’s Hermes, which wraps Kafka and inverts a pull consumption model to a push based model.

In case of Kafka, the consumer controls the rate at which it reads messages. That’s a direct consequence of the pull model.

Hermes has a more difficult job. On one side, it reads messages from Kafka. Then, it controls the delivery to clients, which might involve handling failures. It’s vital for Hermes to take care of guaranteeing a required delivery rate.

Implementing a new algorithm in Hermes was an interesting challenge and we’d like to share our experience. We think it shows some recurring themes with distributed systems. A real world example is always an interesting spark for discussion.

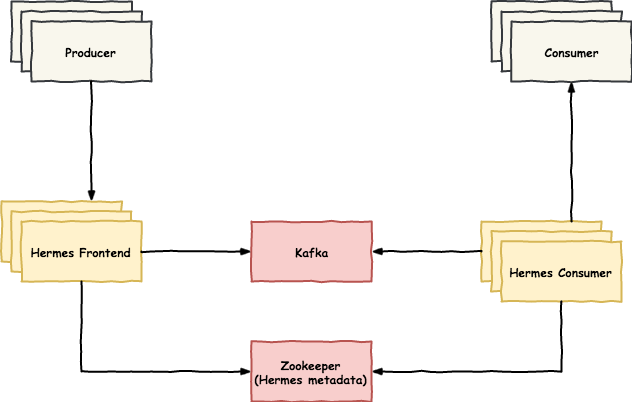

Hermes architecture #

Before we move to the depths of the problem, let’s explain what Hermes actually does from an architectural point of view when delivering messages.

In more detail:

- Hermes’ clients include Producers that publish messages.

- These messages can be read by other clients, called Consumers.

- Messages are stored in topics.

- Hermes Frontends are appending user messages to these topics.

- Then, they’re consumed by subscribers (Consumers subscribed to a topic)

- Hermes Consumers make sure to deliver messages to subscribers via HTTP requests.

Internally, Kafka acts as the persistent message store, while Zookeeper holds metadata and allows coordination of Hermes processes.

Let’s assume the following terms so we don’t get confused:

- topic – a Hermes topic,

- consumer – a Hermes Consumer instance handling a particular subscription,

- subscriber – an instance of a service interested in receiving messages from a Hermes topic.

Hermes consumers work distribution #

Instances of the Hermes Consumers service handle a lot of client subscriptions at runtime and need to distribute work.

An algorithm that balances subscriptions across present consumers is in place, and we configure it as we see fit with a number of parameters.

Among them, there is the fixed amount of automatically assigned consumers per single subscription. We can add more resources to the work pool manually if needed. Consumers can come and go and the algorithm should adapt itself to machine failures and spawns of new ones.

We also have multiple data centers to consider, so the workload distribution algorithm works on a per–DC basis.

This whole algorithm relies entirely on Zookeeper for leader election, consumers’ registry and work distribution.

Factors involved in rate limiting #

First, let’s consider what problems Hermes faces for rate limiting and what are the grounds on which we will need to come up with a solution.

When handling a particular subscriber, there are usually multiple instances of the service. We have load balancing in place which tries to deliver messages fairly to the instances, preferably in the same data center. Scaling the service is the responsibility of the team maintaining it, and what we require is a limit – how many reqs/s can we throw at your service?

That’s all we want to know. We don’t want to know how many instances there are. Especially, as they probably aren’t homogeneous due to our cloud infrastructure running Mesos and OpenStack VMs. We want a single number, regardless of your setup. You measure it, we meet that requirement.

As you will see, we haven’t been using up that number very efficiently, and that’s why we needed to come up with a way to utilise it as best we can.

Note also, Hermes has some logic to slow down delivery when the service is misbehaving, which we call output rate limiting. However, the upper limit for it is the limit we talked about – subscription rate limit (aka max-rate) which is what this article is about.

Motivations for solving the problem #

Our existing approach was to take the subscription rate limit and divide it equally among consumers handling that subscription.

That seems like a good idea at first, but the traffic is not equally distributed at all times. There are two situations where it’s not true. One of them happens occasionally, the second one can hold for months!

First, let’s consider lagging Kafka partitions. We’d like to consume the lag more aggressively,

using as much of the remaining subscription rate limit as we can.

Unfortunately, even if the other N - 1 consumers are not using their share to full extent,

we can’t go beyond limit / N.

Why do partitions lag? For instance Kafka brokers rebalance themselves, which causes some partitions’ consumers to wait a while. A Hermes consumer handling some partitions can crash and the lag grows. And that’s not the whole list.

Second, we need to keep the rate limit across all DCs, as our subscribers can for instance just choose to run in a single DC. Or perhaps writes just happen in one data center, in an active–fallback setup. Consider that the subscriber expects up to 1000 msgs/s (messages per second) and you’re running dc1 as the active one, handling 800 msgs/s at peak time. dc2 is not receiving any messages. With one consumer per DC, you’re limited to 500 msgs/s and the lag grows until the incoming rate falls and you can catch up.

Why not just set the total rate limit higher if we know this happens? The number provided comes from service instances load testing. If we set it above that level, in a scenario, where production rate is higher than the limit a service can take, we inevitably kill a service in production.

Algorithms considered #

There are algorithms for distributed rate limiting, among which the most widely used is token bucket and more sophisticated versions of it.

For our case, there would be too much communication across the network to implement token bucket to get tokens every now and then (even for periods longer than 1 s in advance). Token bucket would require a constant stream of locked writes to a shared counter and coordination for resetting the counter. For hundreds of subscriptions it would mean high contention.

Other implementations require knowing the number of incoming requests. Based on that, an algorithm blocks them from proceeding further. That’s unfortunately a different version of rate limiting.

We aim to deliver every message within a given time period. A message can be discarded only after it’s TTL (described per subscription) expires. Before that, we keep retrying at a fixed interval. Each retry means a delivery attempt. As can be seen, our case of rate limiting is different than a discarding approach. We limit delivery attempts (as opposed to incoming requests).

It would be great to know how much there is to consume (in Kafka terms it’s the lag for the consumer group’s instances), but that’s not something that Kafka APIs provide us with easily.

Therefore, we needed to come up with a solution that is simple and is based on things we can easily extract at runtime. That’s why we based the algorithm on the actual delivery rate.

Algorithm idea #

Setup #

Let’s consider an active consumer that’s running for a particular subscription.

It needs to have a granted upper limit for the local rate limiter of delivery attempts. Let’s call it max-rate.

At a given moment in time, we can measure how many delivery attempts per second were made. If we consider that value with regard to max-rate, we get a number between 0 and 1 – let’s call it rate.

Now, let’s have someone watch all rates for all consumers handling the subscription and decide how to distribute subscription-rate-limit among them. Let’s call this entity the coordinator.

At configurable intervals, the coordinator runs through all the subscriptions and their respective consumers to recalculate their max-rate values.

To make that possible, each consumer reports rate at given interval. We could in fact consider a number of recent values as rate-history and add more sophistication to our calculations, but we wanted to keep it simple for now.

Calculation #

Let’s start with pseudocode and then explain the details:

calculate_max_rates(current_rates, current_max_rates):

(busy, not_busy) <- partitionByBusiness(current_rates, current_max_rates)

if count(busy) > 0:

(updated_not_busy, to_distribute) <- takeAwayFromNotBusy(not_busy)

updated_busy <- balanceBusy(busy)

final_busy <- distributeAvailableRate(updated_busy, to_distribute)

return union(updated_not_busy, final_busy) -- a set with both busy and not_busy

else:

return NO_CHANGE // nothing to update

Narrowing down to a subscription and a bunch of consumers, we might divide them into two groups:

busy and not_busy.

If a consumer’s rate exceeds a configurable threshold, we consider it to be busy and try to grant it more of the share. Symmetrically, not busy consumer falls below the threshold and is a candidate for stealing its share for further distribution.

If more than one busy consumer exists, we’d like to spread the freed amount among them, but also make sure none of them is favoured.

To equalize the load, we calculate the share of each busy consumer’s max-rate in the sum of their max-rate and take away from those above average. We consider that fair. Over time, if they stay busy, their max-rate values should be more or less equal (with configurable error).

Algorithm infrastructure #

The idea seems fairly simple, with a few intricacies and a bit of potential for mistake. However, at a local level, it’s rather easy to grasp.

The challenge lies in implementing it in a distributed system. Hermes is indeed such a system. To make the algorithm’s assumptions hold, we need to wire a lot of infrastructural boilerplate around the simple calculation.

A typical microservice does not communicate with other instances of the same service – it accepts a request, propagates it to other services and moves on. With a coordination problem, such as the algorithm described above, we need to actually pay close attention to many subtle details. We’ll discuss the ones that might be obvious to distributed programming veterans, but perhaps some might sound surprising.

As mentioned below, we use Zookeeper for coordination. We select a leader among the consumer instances, which acts as a leader – the coordinator. At the same time, all consumer nodes are handling subscriptions as usual (including the coordinator).

To help the algorithm, a hierarchical directory structure was created in Zookeeper:

- There is a structure for each subscription’s consumers to store their rate-history (limited to single entry for now – the rate, which we mentioned before).

- The coordinator is the reader of this data. Next to it, the coordinator would store the max-rate.

- Each consumer reads their calculated value at given intervals.

That sounds solid. Let’s ship it.

Well, no.

What can go wrong and how to avoid pitfalls #

The fallacies of distributed computing are well known these days, but one has to experience for themselves, what they mean in practice, to craft an adaptable system.

That’s not all. You want to keep the system running at all times. Deploying different versions of software might be risky if instances of varying versions communicate. We anticipated all of that, but needed to tweak here and there, as some intricacies surprised us.

Here’s the record of some interesting considerations.

Deploying different algorithm versions – constant rate limit for old consumers #

When we decide to deploy the version with a new approach, we must consider what will happen in presence of older instances.

Let’s keep in mind they have a fixed max-rate which is subscription-rate-limit / N.

We can’t take away their share. We have to take that into account when calculating.

To simplify the algorithm, we just use that default for every instance.

How, from the perspective of our algorithm, do we tell if we’re dealing with a new consumer or an old one? Well, one clear indicator is that it doesn’t report its rate. Also, it doesn’t have a max-rate assigned when we first encounter it. This is also true for new consumers we first calculate the value for.

To cover both cases, we simply default to max-rate = subscription-rate-limit / N.

Then, when we have the rate missing for an old consumer, we don’t change any max-rate value.

Caching max-rate #

At a configured interval, consumers reach for max-rate to Zookeeper. What happens if they can’t fetch it? Zookeeper connections can get temporarily broken, or reading can exceed some timeout value. What do we do?

We could default to a configured minimum value, which would definitely be a deal–breaker. We can’t randomly slow down the delivery with such knockout. It takes some time for the consumer to reach full speed (the slow down adjustment we mentioned earlier).

We just ignore such update in that case and carry on with the previous one.

When we start though, we start with minimum, until we find out what the calculated value is.

Caching and conditionally updating current rates #

Every run of the calculation algorithm requires current rates. But issuing hundreds of reads every time is very slow with Zookeeper. Instead, we introduced a cache for the values, which gets updated in the background using Apache Curator caches.

On the other side, rates don’t change that frequently. If they do, quite often it’s just small fluctuations. Therefore, we configure a threshold and consumers report their new rate if it changes more significantly compared to a previously reported value. We save some write overhead too.

Only updating max-rate when required #

Do we need to update max-rates constantly?

When there is no busy consumer, there is no need to grant anyone a higher share, as they’re happy with what they already have. We eliminate most writes to Zookeeper. If consumers are constantly busy, that’s an indicator that the subscription limit is too low.

Dealing with node failures and new nodes #

When a consumer crashes, we need to eliminate that instance from the calculation.

What do we do with the existing rates?

What if a new consumer comes up? We don’t know yet what characteristics it’s going to have.

Just reset everything for simplicity: max-rate = subscription-rate-limit / N for everyone.

The algorithm adapts rather quickly.

Subscription rate change #

One game changer is definitely when a user changes a subscription’s rate limit. How can we tell something has changed? Subscription updates are at a different conceptual level from our calculations.

Every time we attempt to calculate the shares, we sum up currently assigned max-rates and compare it to current subscription-rate-limit and we reset to the default equal share to adjust in case of a difference.

Deployment failure – underlying workload algorithm unstable and fixing it due course #

In the early experiments with the algorithm without some optimizations, consumers would not pick up any work.

The load on Zookeeper grew suddenly.

The underlying workload balance algorithm would take too long to assign any work and nodes would fall out of the registry.

We optimized as much as we could, but still observed an issue.

While deploying the new version, the workload algorithm would trigger a full rebalance of subscription assignments. That in turn caused a chain effect of losing max-rate assignment and triggered re–establishing connections to Kafka at the same time. And that is quite costly due to Kafka partition rebalancing.

Due course we needed to address the underpinnings of workload assignment to make the algorithm stable (hermes-688).

Once we got that right, max-rate calculations played along nicely.

Bug in production #

Finally, not to leave you with a feeling we are so smart and never make mistakes. We actually do, and we learn from them. Most of this article is phrased as a record of what we learned instead of what we got wrong. As developers, we need to stay positive in spite of all those bugs!

The algorithm was running well for weeks. Suddenly things went bad. Some subscriptions would just not process any messages.

We investigated what happened and discovered that someone entered 1 as the rate limit.

We considered a reasonable limit to not fall below 1 per consumer instance. Combined with this given global requirement of 1 the algorithm ended up calculating negative values.

With all the hard thinking about the problem we failed to identify such a basic test.

Nevertheless, it shouldn’t be a deal breaker for everyone, right?

Somewhere else in the code, a task handling the slowing down in case of delivery errors had a loop. Something more or less like this:

try {

for (SubscriptionConsumer consumer : subscriptionConsumers) {

consumer.adjustRate();

}

} catch (Exception e) {

throw InternalProcessingException("Problem calculating output rates", e);

}

Here we have it. One rate adjustment throwing an exception caused the other ones to be abandoned completely!

Moving the try/catch block inside the loop would prevent this from being a major issue. The exception would affect just the subscription with a weird number.

Here, that’s how it ought to be:

for (SubscriptionConsumer consumer : subscriptionConsumers) {

try {

consumer.adjustRate();

} catch (Exception e) {

throw InternalProcessingException("Problem calculating output rates", e);

}

}

Here’s how we addressed the issue: hermes-723.

Yet another bug #

I mentioned we don’t update consumer’s rate in Zookeeper all the time, but only after a significant change.

One bug we discovered with that: if the significant update threshold is higher than the business threshold, a consumer would not be considered busy when it actually reached business.

The bug occured long after the algorithm was enabled, as it wasn’t very likely to happen.

We needed to ensure the configuration is valid to ensure the problem doesn’t happen (hermes-743).

Out in the wild (in production) #

Designing a better rate limiting algorithm had two goals:

- Improving lag consumption when particular partitions had hiccups.

- Better utilization of resources when the load varies across data centers.

Let’s check how the algorithm performed in each of these cases.

Lags during deployment #

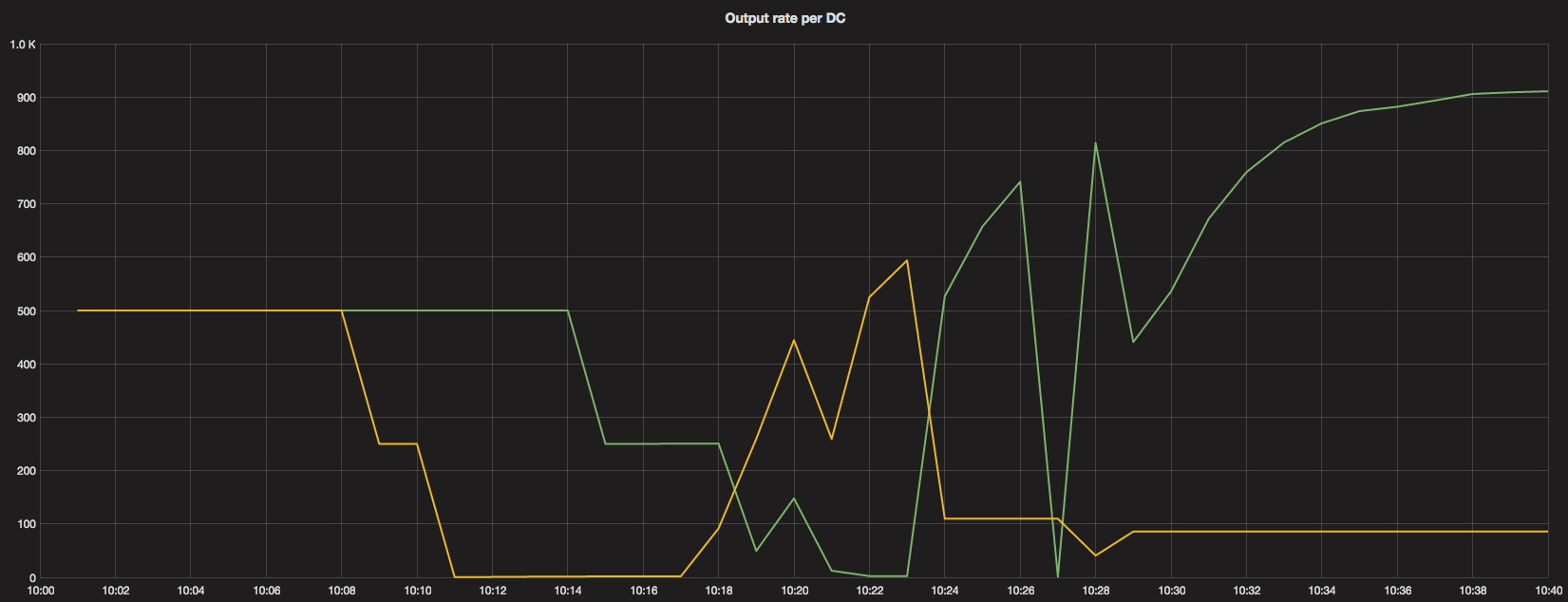

During a deployment, we perform a rolling update.

Some consumers start faster than others and consuming partitions of a particular topic can get some lags.

Around 10:08 a deploy of all instances was issued. From the output rate distribution across data centers, we can tell how they managed.

Dropping to zero means all instances in that DC were starting. Yellow line is the DC in which we first issued deployment.

Let’s have a look at how the consumption went on and how max-rate was distributed. The subscription has a limit of 1000 requests per second.

As we can see, for the short period of time when a consumer starts, a higher max-rate was granted. Then, when the next one kicks in, the previous one is actually done and can give away it’s share. As can be seen, this has happened quite quickly.

The algorithm leaves an uneven distribution, but that’s ok. None of the consumers is actually busy, so they’re satisfied with their current max-rate.

Distributing the rate across data centers #

One of our Hermes clusters operates in an active–passive Kafka setup. Just one DC is handling production data, while the other one gets just a few requests per second.

When we were about to deploy the new version of consumers to this cluster, we noticed two bugs with the old version. Both of them had to do with the way the number of consumers was determined by looking up some metrics in Zookeeper.

As a result, instead of dividing the subscription rate evenly across the consumers, all of them got the full amount. Luckily, the services were scaled enough to handle the load.

Nevertheless, once we deployed a fix for that, we noticed that the subscription limits were not properly defined in some cases. One subscription’s rate limit was lower than the traffic on the topic.

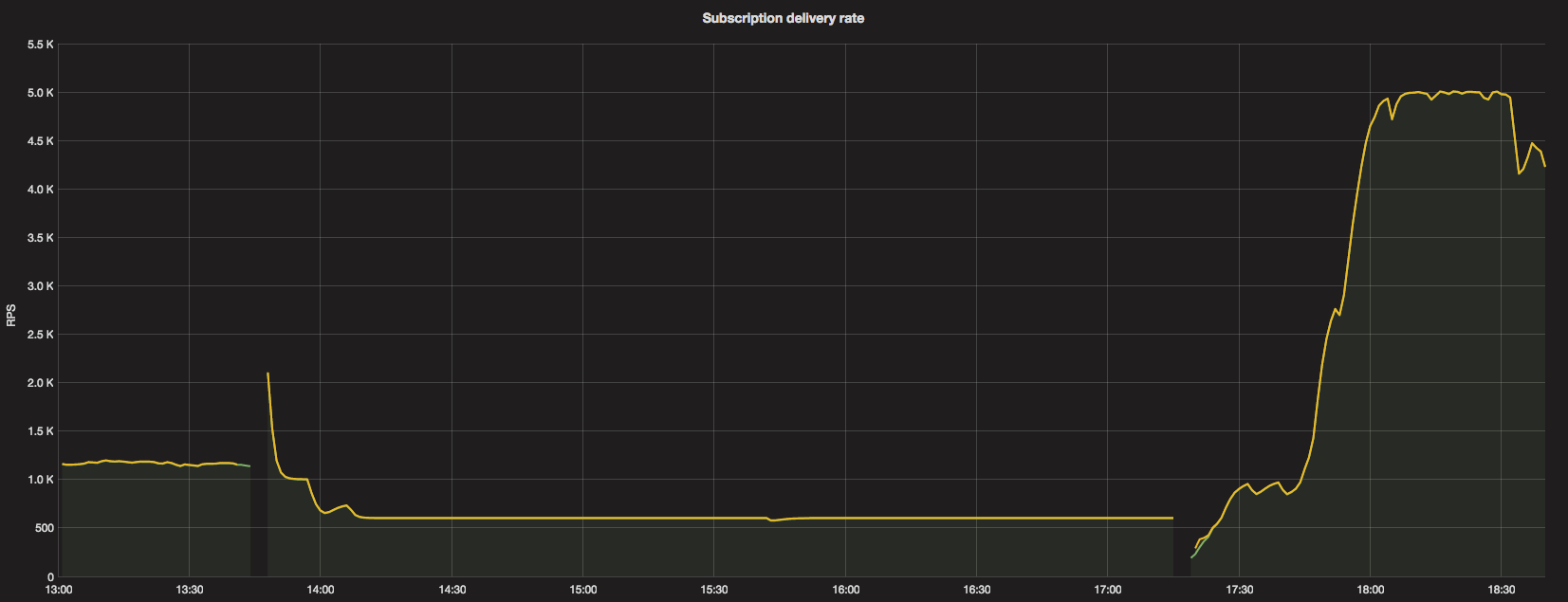

Until 13:45, before we deployed the fixed version, the traffic was around 1.2K reqs/s.

After the rate limit was split evenly, the active DC got around 500 reqs/s limit. That, as can be observed, has impacted the delivery.

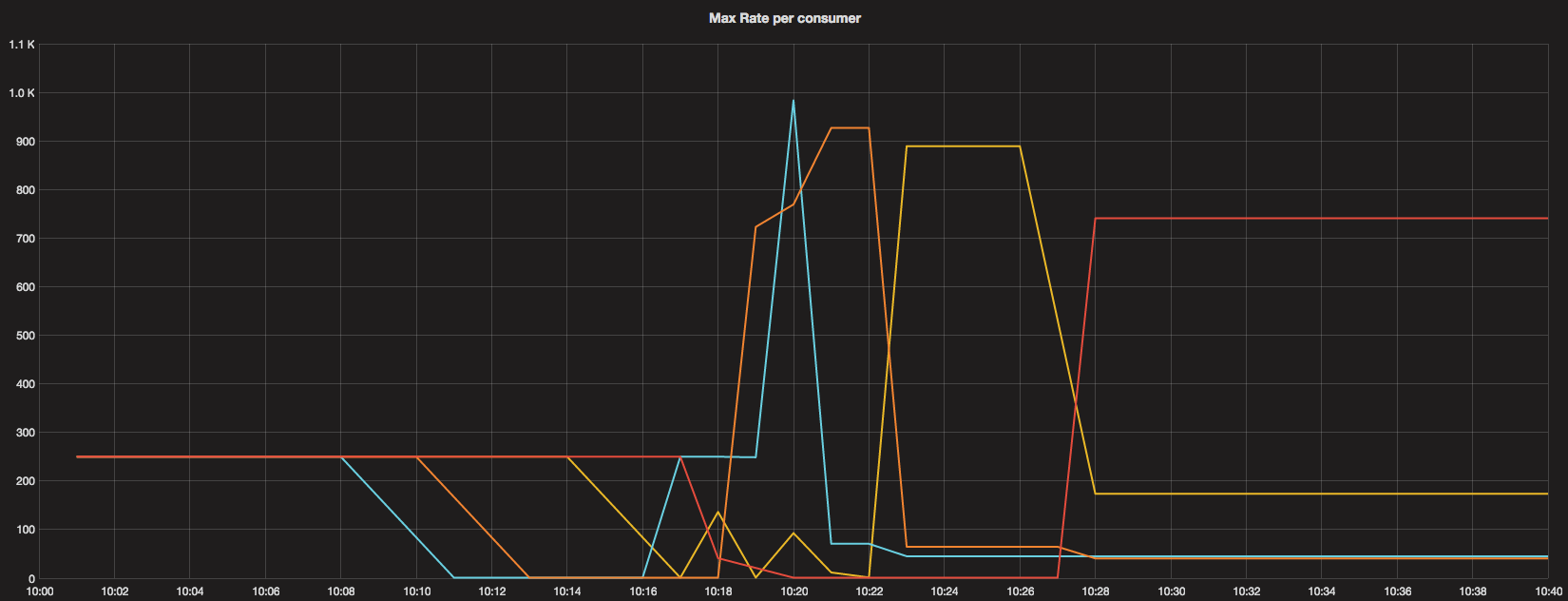

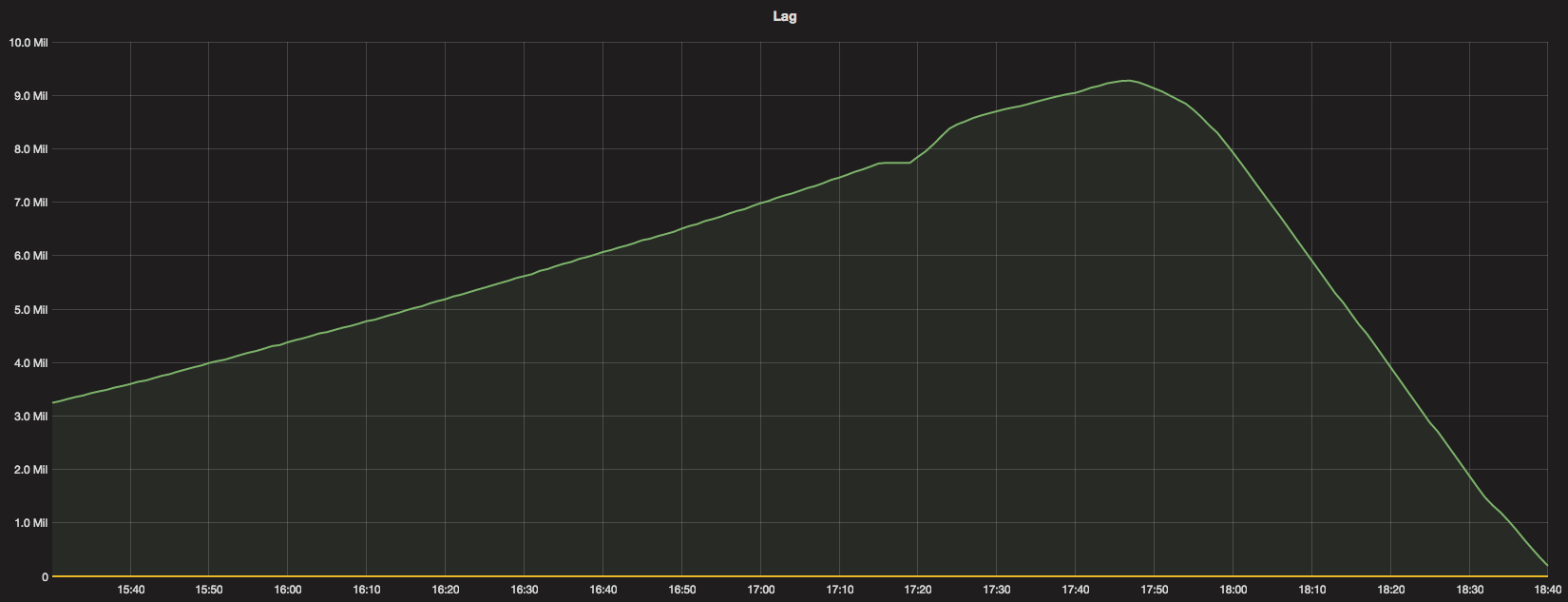

The messages in the queue piled up and the lag was growing. Around 17:15 we deployed the version with the new algorithm and around 17:45 bumped the rate limit to 5000 reqs/s to consume the lag.

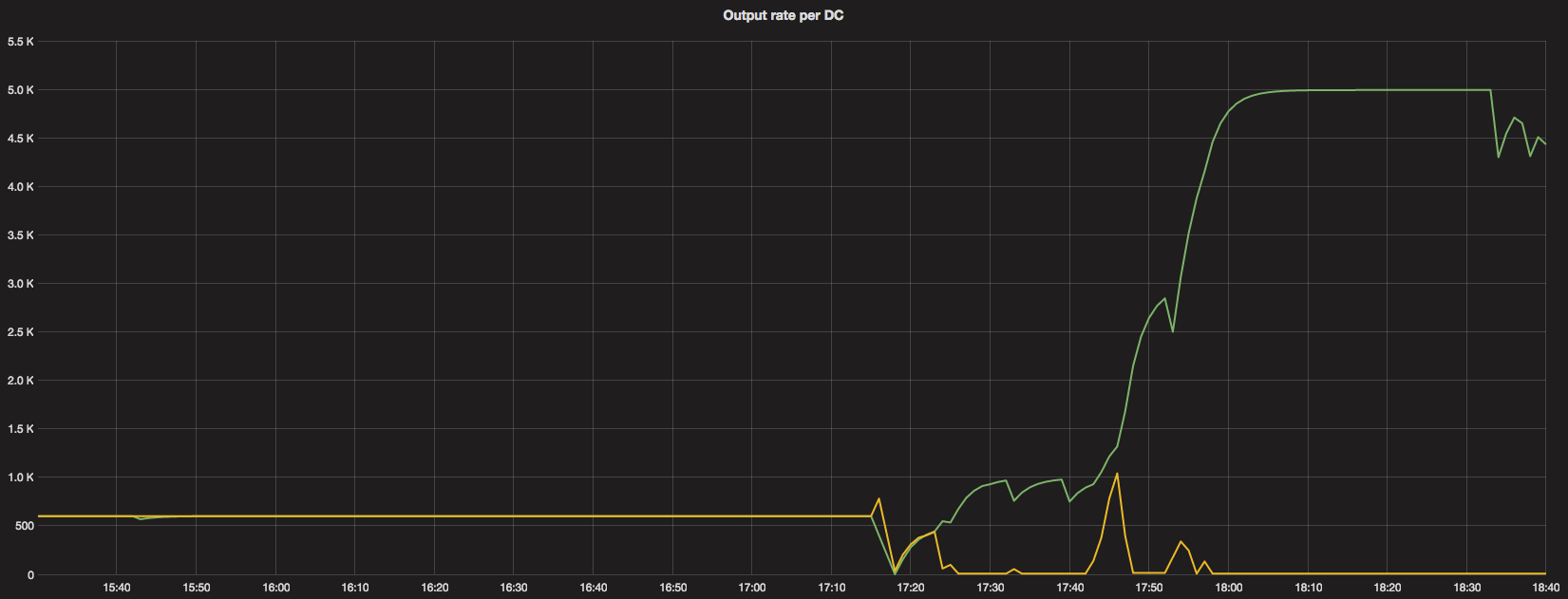

That’s how the output rate per DC looked like after the old version with the fix was deployed.

We can see that between 17:15 and 17:40 the active DC had almost the entire rate limit at it’s disposal, but still needed more.

As we granted it more, the algorithm reacted as expected.

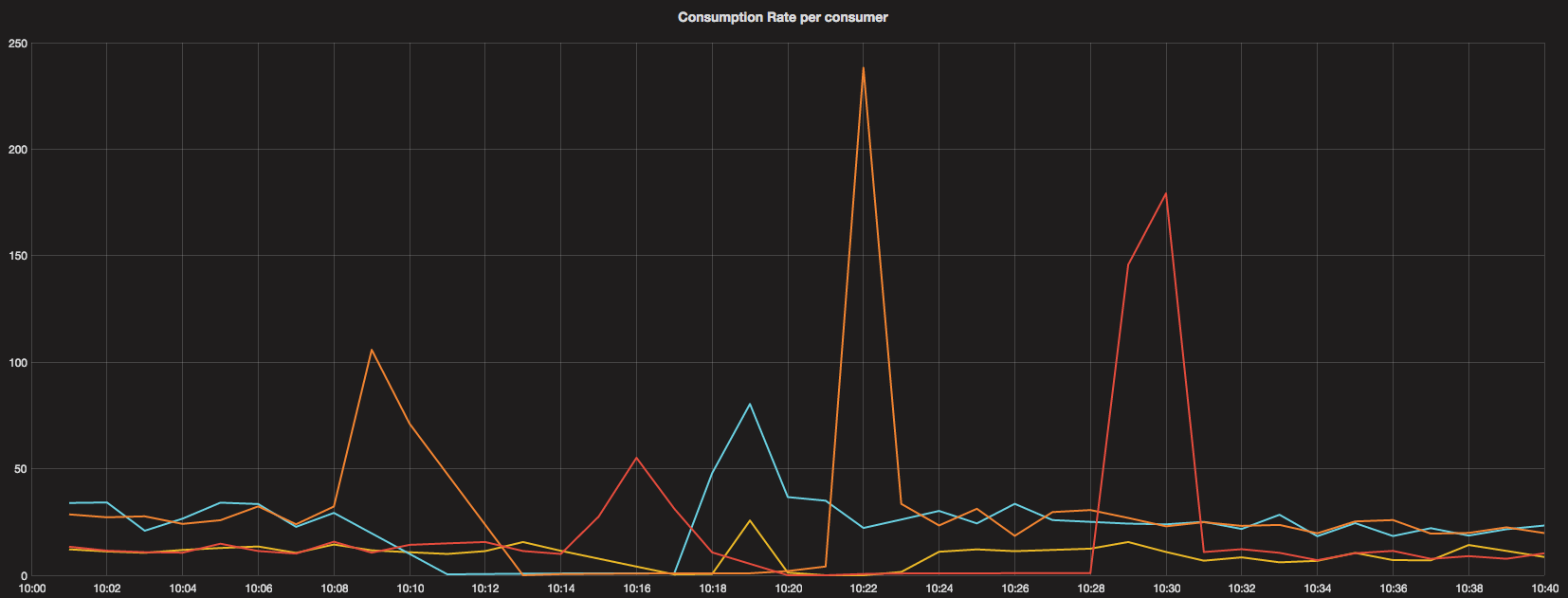

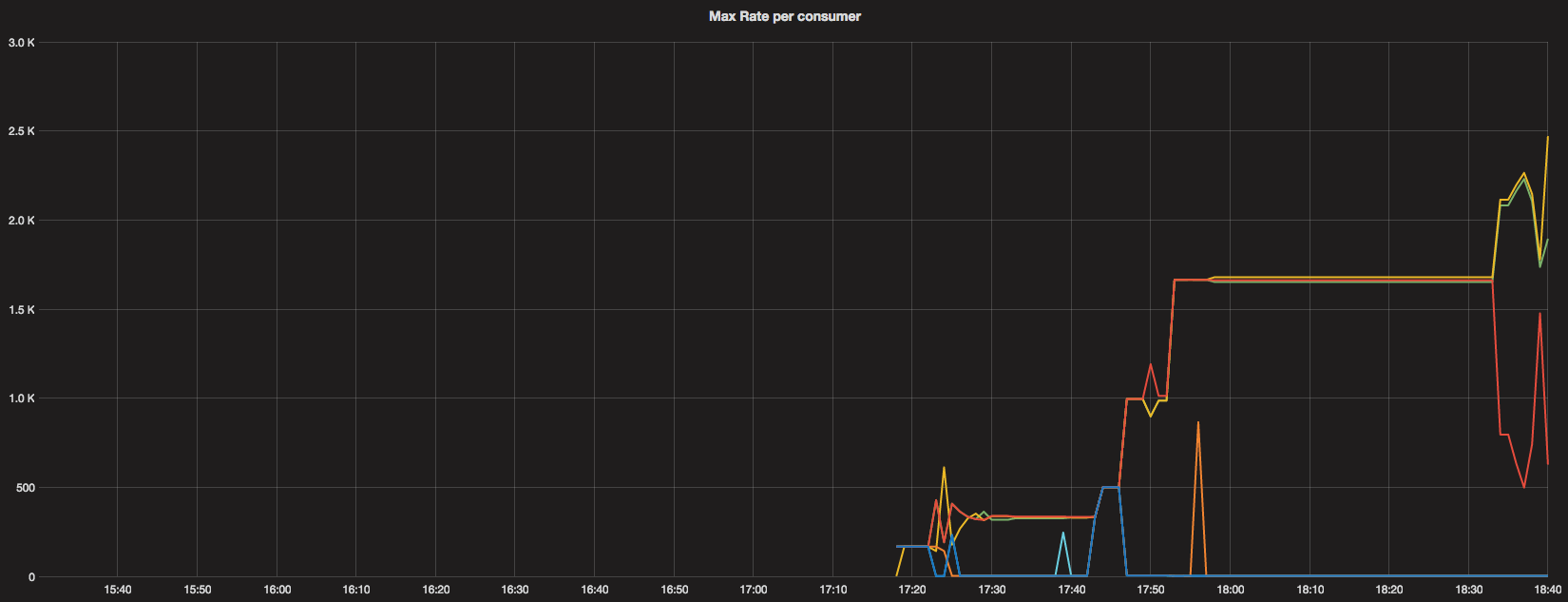

When we deployed the new algorithm around 17:15, max-rate metrics were generated and we can see what the distribution per consumer looked like.

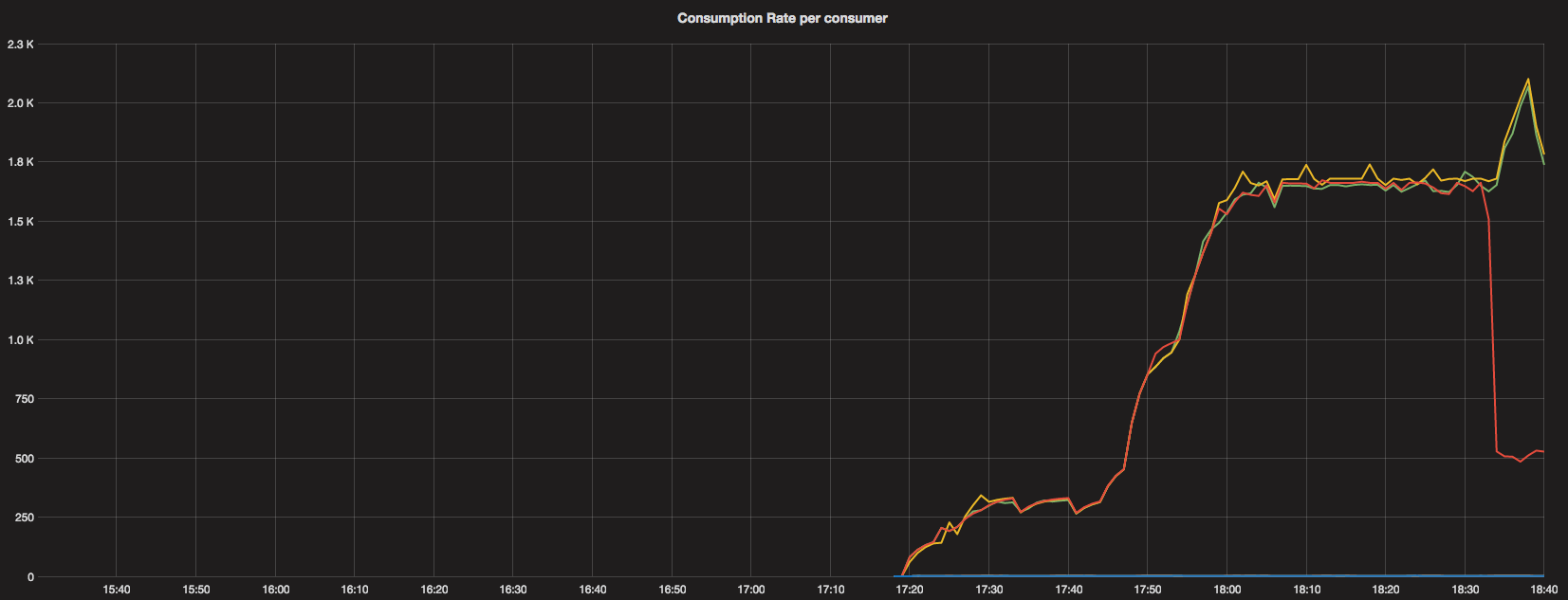

The above graph shows the actual consumption rate by each consumer, on which max-rate calculation is based.

Again, data points start appearing after the new version got deployed (~17:15).

We can see clearly how the lag was growing and started to fall nicely after we increased the subscription rate limit to 5K reqs/s.

Improvements and summary #

We can further improve the behaviour of the algorithm by exploring ideas around rate-history for more smooth transitions.

The algorithm could behave more predictively considering the trend in history, or could otherwise restrain from making rapid decisions. There’s no easy answer which approach to take.

As we keep monitoring how the system behaves over time, we will have more samples to improve the algorithm or leave it as it is.

For now, we have greatly improved the adaptivity of the system to lags and uneven load across data centers.

Further tuning is possible, but we’ve already seen great improvement by deploying the algorithm in current form.

The implementation details are available on GitHub (hermes-611), as Hermes and many other tools are Open Source. Feel free to contribute or share your comments below.