Automated tests with Geb, Spock and Groovy

One of the major goals of software development, apart from actually delivering the product, is to guarantee it is of proper quality and not prone to errors. Big modern systems tend to consist of dozens of smaller pieces, often accompanied by some legacy core or part of legacy system. Each of these, often very different pieces of software communicate with each other in some way, in synchronous or asynchronous way, through REST endpoints, SOAP services or a variety of messaging systems. This leads to new challenges. A failure or unexpected change in one place may lead to a misbehaviour in other parts of the system.

To detect these kinds of abnormal situations we must employ different testing techniques. Unit testing is not enough as it only tests the internals of a part of a systems, usually with all the dependencies mocked. Integration tests also test some part of a system, but in relation to other components. We must remember that the real value for the user is what she sees and what she experiences when using our product. The user does not see dozens of small pieces mentioned earlier, she sees the product as a whole. She does not have to (and shouldn’t) worry about the complexity of the system. To test if her experience is good and nothing unexpected happens we must look at the product with her very eyes. We must use some extra testing techniques in addition to unit and integration tests. In this blog post I’ll write about automated (browser) testing. What is it all about?

Automated browser testing #

The idea is very simple. We prepare various scenarios of common (or error sensitive) user activities. We set various starting conditions and check if the end result is something we expected. Any change to the system that disrupts the process should be caught by the tests. Of course the idea of automated tests is very old, but what I’d like to present here is some new insight in terms of tools used.

The problem #

You might have worked with automated tests using Selenium and Java. This works just fine, but in my opinion Java is not a proper tool for this type of tasks. Its overall simplicity and lack of flexibility may be a perfect solution in the application itself, but in testing I find it too limiting. I feel like using Java here degrades the readability of the tests. You also might have worked with JBehave, which was greatly described by Grzegorz Witkowski in his blog posts about Acceptance testing with JBehave and Gradle. It provides some kind of a high level abstraction, which some people do like while others do not.

For me tests should be short, simple and readable. It is a place where DSLs shine.

The solution #

The very moment I switched from JUnit/Mockito combo to Groovy and Spock in unit and integration tests I never looked back. The beauty of Groovy, combined with the simplicity and readability of Spock are worth trying out. We began to use Groovy and Spock in all our newly created products, but at the same time we used to write our old Selenium/Java automated tests. And they were ugly…

Sure there are plenty of alternatives available. You can use PHP, JavaScript, Python, Ruby. But we already use Groovy in our tests. Why should we change our technology stack for automated tests?

Fortunately we don’t have to. Geb is the answer. It is kind of a wrapper on top of Selenium WebDriver and enriched with Groovy and Spock syntax (using Spock is optional). I strongly recommend you’d start your adventure with Geb from this starter: Geb starter project

It is a sample project, prepared to run browser tests in Firefox, Chrome and PhantomJs. It is very simple to add your own runner (for continuous integration purposes for instance). It’s based on Selenium WebDriver so you must remember you may use and easily migrate all the settings you used for standard Selenium Java tests. You may now ask what’s so nice about Groovy, Spock and Geb? Let’s take a look at some code.

The tool #

We’ll look at Allegro webpage through a shopping cart example and try to write some very basic test. We’ll click the cart icon on the main page and check if we are redirected at an empty cart page.

In our example we’ll use gradle for building our project and managing its dependencies. For the start let’s clone the repository of Geb gradle example.

git clone https://github.com/geb/geb-example-gradle

Before we begin creating tests we need to change the baseUrl setting in GebConfig.groovy file. Let’s set its value to http://allegro.pl.

Creating pages #

When the user visits our website he enters some page. In our test it will be the Allegro main page. In Geb (as in standard Selenium tests) there is a concept of a webpage, where you may gather all the elements related to a certain URL.

package pages

import geb.Page

import modules.CartStatusModule

class AllegroMainPage extends Page {

static url = '/'

static at = { title.startsWith 'Allegro.pl' }

static content = {

cartStatus { module CartStatusModule, $('#cart-status-header') }

}

}

That is a veeery shortened declaration of Allegro main page, but it’s enough for our example. The most interesting part here are the three static properties:

urlis used to set the URL address of the page. It might be used in test to move to that address after giving a command:to AllegroMainPageatis used to verify we are on the expected page (here we check if the title starts withAllegro.plstring). It might not be the best choice, but it’s just an examplecontentsection contains definitions of all the components available on the page. Here we have just one component (cart status) and it’s defined as a module pinned to an element with idcart-status-header. As you can see, selectors in Geb are defined in a jQuery-like way and are very readable.

Extracting page fragments to modules #

Let’s see what cartStatus module is:

package modules

import geb.Module

class CartStatusModule extends Module {

static content = {

icon { $('.sprite', 0) }

}

}

Module is a (usually reusable) part of a page. We may also use it to split a page into smaller components. Cart status (similar to search box or menu) is visible on almost every Allegro page and defining it on every page could be considered a violation of the DRY principle. We may fix that by defining this element in a separate module and including it as needed. The definition of a module is very similar to the definition of a page. We also have a content section. Here we say content has an icon with a given selector. We also need a cart page:

package pages

import geb.Page

class CartPage extends Page {

static url = '/cart'

static at = { title.startsWith 'Koszyk' }

static content = {

cartItems(required: false) { $("ul.items-list li") }

}

}

As previously it is very simple. The site is available at /cart URL. We verify we’re on the cart page by checking if the title starts with Koszyk

(koszyk means cart in Polish).

The page can have many content items defined, some of them are obligatory, but others are not required. CartItems are not available when there are no

items in the cart, so we must mark it as required: false.

Writing our first spec #

Now let’s take a look at a simple test:

package specs

import geb.spock.GebReportingSpec

import pages.CartPage

import pages.AllegroMainPage

class AllegroToCartSpec extends GebReportingSpec {

def "should redirect to empty cart when cart status icon clicked on main page"() {

when:

to AllegroMainPage

and:

cartStatus.icon.click()

then:

at CartPage

and:

!cartItems

}

}

We may read it as: “ When we go to the main allegro page

and click the cart status icon

then we are at cart page

and there are no cart items on the page ”.

In my opinion it is a perfect combination of nearly JBehave-like readability of the tests and simplicity of their development provided by the Groovy language.

Running the test #

Now we’d like to run the test. The basic setting provided in Geb gradle example allows us to run Firefox, Chrome and PhantomJs tasks.

To run a Firefox task we run:

./gradlew firefoxTest

In a similar way there exist chromeTest and phantomjsTest tasks.

To run all tests on all browsers, just run:

./gradlew test

To run a single test in Firefox run:

./gradlew -DfirefoxTest.single=Allegro* firefoxTest

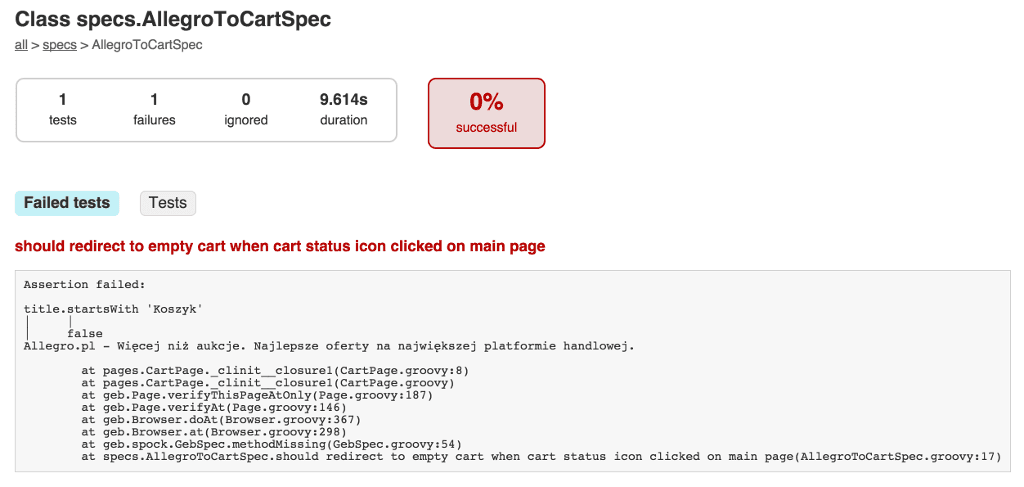

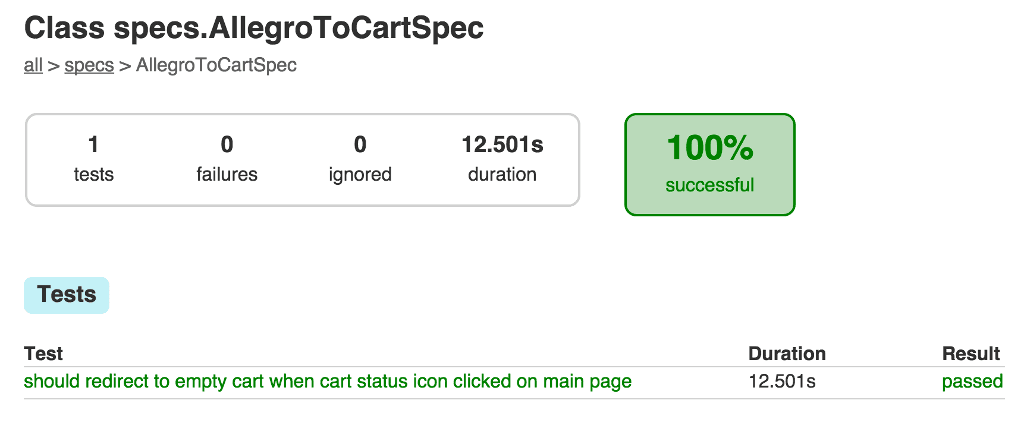

After the test completes you receive a report in html format. Below I placed examples of both a failed…

… and a successful test report.

I think that they are quite readable.

Summary #

Simple as that. Of course the example presented here is very basic. There are many more possibilities. If for some reason you don’t like Spock, you may use standard jUnit style. You may also integrate the tests with Spring, if that’s what you need. Once again I encourage you to take a look at Groovy, Geb and Spock. Try them out and experiment with the example project.

Make your automated tests simple and readable!