Playing with fire — a Scrum experiment

The aim of this blog post is to summarise an experiment that took place between two scrum teams at the end of 2014 and to share our lessons learned. Have you ever worked in close cooperation with another team? Of course you have. But how close is close? Have you ever wondered what happens when you go one step further than cooperation and you actually mix two teams, stir or even shake? During that time we discovered a lot about team dynamics, sources of inner responsibility that is essential for any team to make commitments and what are the biggest obstacles on the way towards self-organisation. So, without further ado, let the story begin…

Background #

Once upon a time in the very middle of the middle of a large e-commerce kingdom, there was a Finance product area, and in the area two Scrum teams, and in the teams a bunch of talented developers and a visionary Product Owner. Both teams were given a common goal of creating a Refunding System. They also had their own products to continue working on: Flexible Pricing and admin panels for Flexible Discounting.

The idea behind the experiment was to join two teams so that the knowledge about all Finance products would be better spread across all developers and to accelerate taking out Refunding to the new Java world. Moreover, we wanted to see how it would work out to form Scrum teams from a pool of developers who would freely move around teams every iteration.

To wrap it up, we started with a pool of 14 developers (including 2 technical leaders), 1 Product Owner, 2 Scrum Masters and 3 products to develop. Timeframe for the experiment was 3 months and we assumed that every iteration different scrum teams would be created out of the 14 developers; number of teams and their composition depended solely on sprint goals and developers’ decision on how to organise around the work to complete. Most often, we worked in three scrum teams of varying composition, however, it wasn’t a rule. For the purpose of this article, “Team” refers to the whole pool of 14 developers, likewise “teams” or “sub-teams” mean work groups established for the sprints.

Course of experience — a few facts #

As it usually happens in fairytales and wonderlands, the beginning of the story was peaceful. We started with a workshop with users to define product backlog, we determined a new reference story to have a common definition of a story point, and planned first sprints so that we could deliver value from the very start. And after the first iteration, the Team actually delivered first simple version of a tool for making refunds. At this point the villain made his appearance. Even worse, it was an unknown villain, dark, masked and impossible to capture.

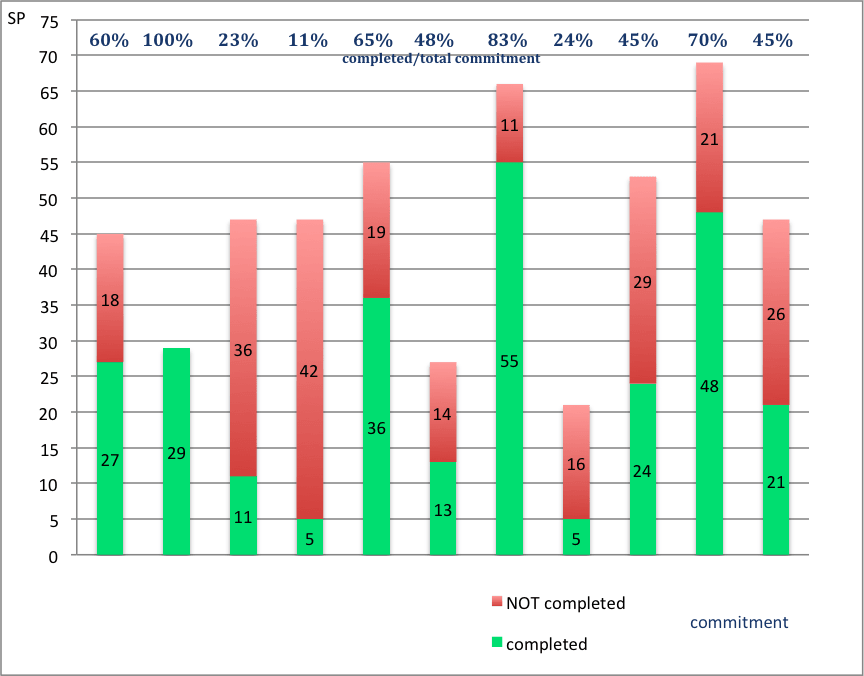

Over time, judging by commitment and velocity charts, Team’s performance showed little predictability. Moreover, the less teams delivered, the more they committed to the following sprints, keeping the velocity at the roller coaster. We kept introducing improvements focusing on different means of work organisation for the whole group of developers in a pool, i.e. grouping around the particular product with a majority of developers already familiar with it.

Astonishingly enough, even though they almost never delivered what they had committed to, after few Sprints developers started to stress that they were somehow bored and that they did not create what they were capable of. What is more, they felt that the whole product development should have been finished already and the pace they were working at left much to be desired. They also honestly admitted that the reason was their lack of responsibility for the process, for the product and for the Team itself. Nobody felt accountable, starting from the review meetings, where only one person was showing the results of work of several sub-teams created for a given iteration, to the whole process they were at. As a remedy to this, Team decided that every sub-team should have their own Sprint goal, a person responsible for the demo and they were even creating team names every iteration to build some identity of newly formulated groups.

Who is the villain? #

While work progressed we discovered more and more obstacles joining two separate teams together:

- Each team had its own culture, habits, style of work and cooperation.

- Each team had its own coding standards and different definitions of “high quality”.

- The more people, wider the perspective on problems to solve, but it also became more difficult to reach consensus or even any agreement.

- The more people, the more difficult it was for the team to self-organise.

Furthermore, creating new teams with different members every sprint resulted in unconstructive retrospectives that were focusing on high-level work improvements for the whole pool of developers and made it impossible to search deeper or to draw conclusions for sub-teams. It also caused a lack of affiliation within any team and some developers started complaining that they prefer to focus on just one product they can feel responsible for.

Last but not least, among all of the improvements, the one involving team names and separate goals for sub-teams was actually the one touching the roots of a bigger problem – lack of the inner responsibility. But can a trait such as responsibility be forced onto people? Can it be learned? If you cannot use the magic wand and cast a spell “be responsible from now on”, all you can do is to search for reasons behind and to create an environment fostering it.

Lessons learned #

No matter if you just cooperate with another team or you want to shuffle developers between teams, it is vital to start with establishing a contract to define how you organise joint work and what coding standards you follow. And it is not enough just to merge your Definition of Done. Without going deeper and openly discussing standards, architecture or product development vision you end up making assumptions and it never works when there is more than one person involved.

Patterns for hyper-productive teams emphasise the importance of stable teams. Since these concepts were published, many companies proved that if they shuffled members of the teams at the beginning of every project, they were not able to reach hyper-productivity. Keeping teams stable enables them to establish their capacity and makes it possible for the Product Owners to plan product releases. What is more, stable teams develop their own identity that in turn helps them feel unique and stronger when facing new problems to solve. Have you ever got annoyed after yet another question from Scrum Master how to work together as a team to accomplish the Sprint goal? We keep drawing your attention to teamwork, among others to inspire collective ownership.

One of Scrum values is commitment. As a developer you commit to deliver a piece of work that is high quality and meets customer needs. It is a commitment to your team, to the client and to yourself, that’s why it’s directly linked to responsibility. The problem we encountered was lack of it towards the team as every sprint developers worked in different sub-teams so it was impossible to create any sense of belonging to a group. Also frequent shifts between products made it difficult for developers to feel accountable for business effect. An environment fostering sense of accountability requires stable teams and stable product for a period longer than few weeks.

But there is more to it. Taking responsibility for something entails making an effort and whenever there is a slight chance that somebody else could take it on, it is a natural impulse to withdraw yourself. In this particular case, teams behaved as if the experiment and work environment conditions had been imposed on them and as if they did not have any impact on it. Why, you ask? Perhaps because, as a Scrum Master, I wanted them to succeed and to reach favourable conditions of joint work so much that I did not leave any room for teams to take ownership of the process. This is a lesson for Scrum Masters and leaders. Sometimes when you think that you are helping the team by removing any burdens, you are actually disturbing as the self-organisation is taken away.

We also learned that even if you are bright enough to notice several problems at once, you cannot introduce several improvements at the same moment. Isolation is essential for finding out which improvements really help and to verify the true impact of impediments and solutions. Moreover, whenever you come up with an experiment to try, define precisely its boundaries and make sure that everybody involved knows them. Think of entry and exit conditions for the experiment, what is its goal, what you want to verify and under what terms it is more sensible to stop the experiment. Better safe than sorry, experiment frames and exit conditions are your safety valve.

Conclusions #

Majority of fairytales have a happy ending. This story ended with a product not delivered, technical debt and frustration of team members. However, if I were to evaluate the experiment, I would certainly not say it ended badly. We have learned a lot, drew conclusions and we know how to do it again, better. Scaling Scrum is always a difficult concept in practice. Teams that are to work together, need time to work out the way they are the most productive towards a common goal.

- Start with defining clear entry and exit conditions of any experiment you participate in.

- Allow time to establish detailed working contract when there is more than one team working on the same goal.

- Scrum events apply to scrum teams, if there are more teams involved at once, do not throw them into the same basket, it’s more effective to let them go through the whole sprint individually and then synchronise.

- Keep teams stable, frequent shifts have detrimental effect on group dynamics.

- Allow teams to have a responsibility for a product being developed, frequent context switches inhibit accountability and impede work.

- Trust yourself and your teams.

That is the thing about experiments: they cannot end well or bad. As long as they give you a chance to verify your assumptions or ideas, they serve their purpose. And the more you try, the higher your chances to succeed. Do not put off for tomorrow, define the frames, isolate the environment and verify your ideas. Verify fast in small pieces, learn fast, fail even faster and start over.