Aspects in Spring

This post is an introduction to the mysterious and alien world of aspect-oriented programming, or aspects for short. At first sight it is difficult to understand why to use aspects and how a project can benefit from this technology. The simplest use case where we can use an aspect is logging. I believe that everyone saw, or even wrote on their own, a piece of code where the business logic was interweaving with infrastructure code:

public void WarehouseOrder calculateOrder(OrderContext context, Item item, DateTime orderDate) {

...

WarehouseStatus status = warehouse.getStatus(..)

LOG.info("Warehouse status: {}", status);

...

Order order = orderFactory.createOrder(orderContext, orderDate);

LOG.info("Order: {}", order);

...

}

However simple this example may be, please remember that sometimes it is necessary to write more detailed information to

logs and, as a result, the logging code becomes more complicated.

We can see that the business code is affected by the logging code. The calculateOrder method should be responsible for only one thing, i.e. calculating orders.

Unfortunately, it has to perform more operations and log information. What is worse, we may want to log the result of

warehouse.getStatus and orderFactory.createOrder not only in the calculateOrder method but in other

methods in our business code. Imagine that there is a request to change logging details. We would have to modify every

line of code related to logging. Fortunately, there is another way to implement this.

Using aspects ensures that the logging logic (i.e. infrastructure code) remains in one place and can be reused everywhere in the project. Aspect-oriented programming allows software developers to separate the infrastructure code from the business code and, as a result, the business code is clearer and easier to maintain. Moreover, aspects may be used to modify third-party libraries. This feature can be very useful because we can employ an aspect to add, for example, a security feature instead of patching (or fixing) a library.

Let us create an aspect for each type of logging to the code from the previous snippet. The first aspect logs the results returned by

warehouse.getStatus and the second aspect logs results returned by orderFactory.createOrder.

The following code shows the aspect that logs WarehouseStatus (an aspect for logging Order looks very similar):

@Component

@Aspect

public class WarehouseStatusLoggingAspect {

@Around("execution(* com.company.Warehouse.getStatus(..))")

public Object aroundLegacySystemWrapper(final ProceedingJoinPoint proceedingJoinPoint)

throws Throwable {

final WarehouseStatus status = (WarehouseStatus) proceedingJoinPoint.proceed();

LOG.info("Warehouse status: {}", status);

return status;

}

}

We can now revisit the calculateOrder method:

public void WarehouseOrder calculateOrder(OrderContext context, Item item, DateTime orderDate) {

...

WarehouseStatus status = warehouse.getStatus(..)

...

Order order = orderFactory.createOrder(orderContext, orderDate);

...

}

Basic concepts #

Aspect-oriented programming (AOP) is a programming paradigm that aims to increase modularity by allowing for the separation of cross-cutting concerns. However vague this may seem, the idea behind aspects is really simple. Computer science describes concern as a particular set of information that has an effect on the code of a computer program. To be more specific, in object-oriented programming, we describe concerns as objects. Consequently, in functional programming we describe concerns as functions. Finally, in aspect-oriented software development we treat concerns and their interactions as constructs of their own standing. Sometimes module divisions in a program do not allow for one concern to be completely separated from another, resulting in cross-cutting concerns as they “cut across” multiple abstractions in a program. A good example of a cross-cutting concern is logging, because logging strategy affects logged parts of the system. Other examples of cross-cutting concerns are:

- synchronization,

- memory management,

- persistence,

- transaction processing,

- internationalization and localization.

AspectJ encapsulates cross-cutting expressions in a special class called an aspect (since we use Spring here, all aspects are well-known Java classes). For example, an aspect can alter the behavior of the base code (the non-aspect part of a program) by applying advice (additional behavior) at various join points (points in a program) specified in a query called a pointcut (that detects whether a given join point matches). An aspect can also make binary-compatible structural changes to other classes, such as adding members or parents (this is not discussed here).

Aspects in Spring #

Let us assume that we have a business component in Spring which is responsible for transferring money from one account to another. According to the business model, a user is charged for some transfer operations, while other operations remain free of charge. This mechanism is implemented in the legacy system. We would like to log calculated fees in order to be sure that the legacy system works properly.

@Component

public class MoneyTransfer {

private static final Logger LOG = LoggerFactory.getLogger(MoneyTransfer.class);

private LegacySystemWrapper legacySystem;

public void transferMoney(final MoneyTransferParams moneyTransferParams) {

Fees fees = legacySystem.calculateFees(moneyTransferParams.getCurrency(),

moneyTransferParams.getUser());

LOG.info("Calculated fees{}", fees);

...

}

}

We can see that business code is affected by logging. In this simple example the effect is marginal, but imagine that we would like to perform some kind of verification before transferring money. For example, we are fetching the data from the legacy system and want to know whether these data are correct or not. Moreover, we would like to keep the verification code away from the business one to make code cleaner and easier to maintain. Thus, we could simply create another component for that purpose, but what about other usages of the legacy system? Since we cannot modify the existing library and we would like to separate verification code from the legacy system wrapper, we use an aspect.

@Component

@Aspect

public class LegacySystemWrapperAspect {

@Around("execution(* com.company.LegacySystemWrapper.calculateFees(..))")

public Object aroundLegacySystemWrapper(final ProceedingJoinPoint proceedingJoinPoint)

throws Throwable {

final Fees fees = (Fees) proceedingJoinPoint.proceed();

verify(fees);

return fees;

}

}

The code above presents a typical aspect. Before each call of the calculateFees method from the LegacySystemWrapper

class the aroundLegacySystemWrapper method is invoked. The call of calculateFees is actually triggered by

proceedingJoinPoint.proceed(). The result of the calculateFees call is processed in the verify method. After the

verification, it is returned to the code which has called calculateFees. It is crucial to realize that the whole

process is completely transparent to the code which calls calculateFees. Thanks to LegacySystemWrapperAspect

we can rewrite the MoneyTransfer class:

@Component

public class MoneyTransfer {

private LegacySystemWrapper legacySystem;

public void transferMoney(final MoneyTransferParams moneyTransferParams) {

Fees fees = legacySystem.calculateFees(moneyTransferParams.getCurrency(),

moneyTransferParams.getUser());

// normal flow here

}

}

We can see that the MoneyTransfer class have just become cleaner. The fees verification logic is always executed

and the client code is completely unaware of it.

The execution(* com.company.LegacySystemWrapper.calculateFees(..)) expression is a pointcut which captures

calculateFees invocations. It is also a join point which uses the pointcut. Moreover, the @Around annotation

is AspectJ’s advice and the LegacySystemWrapperAspect class is an aspect.

Aspect configuration in Spring #

Let us look at aspect configuration in a Spring project. The traditional way is to add proper entries in the XML configuration:

<aop:aspectj-autoproxy/>

Next, we can create aspects in the same way as ordinary components:

<bean id="aspect" class="com.company.CompanyAspect">

...

</bean>

And the class itself looks exactly like LegacySystemWrapperAspect which we have seen above.

We can also configure aspects with Java annotations themselves. In order to do that we need a special Spring configuration:

@Configuration

@ComponentScan

@EnableAspectJAutoProxy

public class ApplicationConfiguration {

}

Again, an aspect class looks the same as before. It is an ordinary Spring component with the @Aspect annotation.

Every aspect created in this way is being managed by the Spring Container and experiences the bean lifecycle.

Real-life example #

In order to understand how aspects work and how they can be utilized, let us look at a real-life use case. Imagine that there is a service deployed in the cloud that uses other services to do its job. As a result, its performance depends heavily on the performance of other services. Sometimes when it takes too much time for it to serve a request, it is hard to find the cause of the delays without gathering proper statistics. In order to make it easier to track performance issues, the service monitors calls to external services by collecting statistics:

public class HealthMetrics {

private Timer callTimer;

private Meter exceptionMeter;

public HealthMetrics(MetricRegistry registry, String adapterName, TimerFactory timerFactory) {

final String timerName = adapterName.concat(".timer");

callTimer = timerFactory.createTimer();

registry.register(timerName, callTimer);

exceptionMeter = registry.meter(adapterName.concat(".exception.meter"));

}

@SuppressWarnings("all")

public Object aroundCall(final ProceedingJoinPoint proceedingJoinPoint) throws Throwable {

final Timer.Context context = callTimer.time();

try {

final Object result = proceedingJoinPoint.proceed();

return result;

} catch (Exception e) {

exceptionMeter.mark();

throw e;

} finally {

context.stop();

}

}

}

The aroundCall method is used by aspects to gather call time statistics and to measure how often exceptions occur.

The following example shows an aspect which gathers statistics related to MongoDB:

@Aspect

@Component

@Order(0)

public class MongoHealthAspect {

private final HealthMetrics healthMetrics;

@Autowired

public MongoHealthAspect(final MetricRegistry registry, final TimerFactory timerFactory) {

healthMetrics = new HealthMetrics(registry, "adapters.db.mongo", timerFactory);

}

@Around("execution(* org.springframework.data.mongodb.repository.MongoRepository.*(..)) ||"

+ "execution(* pl.allegro.rubicon.quoting.db.mongo.MongoCommonPriceListRepositoryCustom.*(..))")

@SuppressWarnings("all")

public Object aroundMongoDbCall(final ProceedingJoinPoint joinPoint) throws Throwable {

return healthMetrics.aroundCall(joinPoint);

}

}

Despite the fact that this class is short, there are several things worth mentioning.

To begin with, note that we have two pointcuts here. The first one captures calls to any method from the

MongoRepository class, while the second one captures calls to any method from the

MongoCommonPriceListRepositoryCustom class. Secondly, since this aspect is responsible for

gathering performance statistics, we want it to be the first aspect being fired when any MongoRepository

or MongoCommonPriceListRepositoryCustom method is invoked. That is why we use @Order(0). It is worth

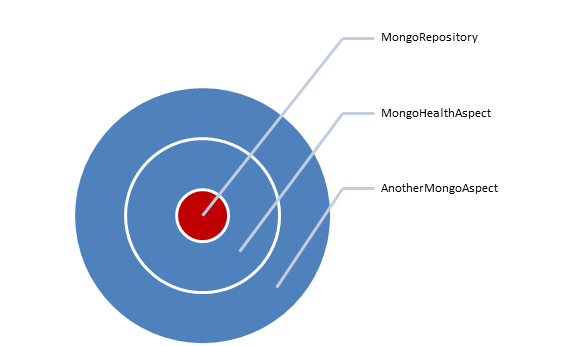

mentioning that you can have many aspects with their advice and pointcuts focused on the same class or method.

This will create an onion-like structure with the targeted class in the center. In this structure every call of

proceedingJoinPoint.proceed() from outer layer calls an aspect method from inner layer.

Aspects from the inside #

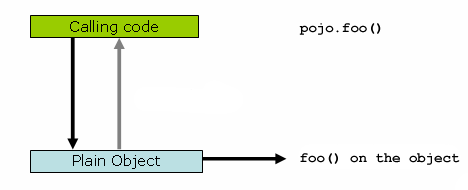

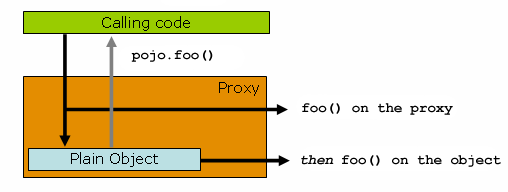

When it comes to aspects, it is essential to understand the difference between calling a plain old Java object versus calling a proxy:

(images from the Spring documentation)

Aspects in Spring are implemented by default as Java standard J2SE dynamic proxies, which enable an interface or any

set of interfaces to be proxied. However, when business objects do not implement any interface, Spring uses

CGLIB instead. This results in Spring aspects limitations as you can only advice

public methods. Have you ever wondered why the @Transactional annotation on a private method did not work?

Now you know why — @Transactional support is implemented as a Spring aspect and, as a result, cannot advise private methods.

Testing aspects #

Testing an aspect may be a difficult task due to their nature as they require at least one Java class, method

invocations of which will be captured. In order to make the testing environment as small as possible, a good solution

is to separate the logic of advice from the aspect itself.

We could see that in the code presented above there are two classes – HeathMetrics and MongoHealthAspect.

This composition allows us to test our code properly. Unit tests of HealthMetrics only require

ProceedingJoinPoint to be mocked. The logic of HealthMetrics can be tested easily, without the need

of creating and setting up another component.

@Test

public void shouldHealthMetricsBehaveWell() {

// given setup here

// when

healthMetrics.aroundCall(Mockito.mock(ProceedingJoinPoint.class));

// then HealthMetrics behaves well

}

However, if we have not had such a nice solution and had merged HeathMetrics

and MongoHealthAspect into one MongoHealthMetricsAspect class,

testing it would require much more effort. First of all, we would have to set up

Spring context because in Spring AOP aspects are, in fact, proxies. Secondly, we

would need an object whose method calls will be intercepted. We could use Mockito

to create a mock. However, this mock would have to be a Spring bean in order to

be proxied. All this would mean that our unit tests have just became context tests.

While writing unit tests for aspects, we may encounter some problems when using

external libraries. For example, CatchException creates its own proxies which

interfere with Spring proxies and, as a result, the object under test may behave

unexpectedly.

Advanced Spring AOP #

In this tutorial we have only seen @Around advice. Here is the complete

list of all types of advice from the Spring documentation:

- before

- after returning

- after throwing

- after finally

- around

When it comes to pointcuts and their designators, we have only seen execution designator. Here is the complete list of all pointcut designators from the Spring documentation:

execution– for matching method execution join pointswithin– limits matching to join points within certain types (simply the execution of a method declared within a matching type when using Spring AOP)this– limits matching to join points (the execution of methods when using Spring AOP) where the bean reference (Spring AOP proxy) is an instance of the given typetarget– limits matching to join points (the execution of methods when using Spring AOP) where the target object (application object being proxied) is an instance of the given typeargs– limits matching to join points (the execution of methods when using Spring AOP) where the arguments are instances of the given types@target– limits matching to join points (the execution of methods when using Spring AOP) where the class of the executing object has an annotation of the given type@args– limits matching to join points (the execution of methods when using Spring AOP) where the runtime type of the actual arguments passed have annotations of the given type(s)@within– limits matching to join points within types that have the given annotation (the execution of methods declared in types with the given annotation when using Spring AOP)@annotation– limits matching to join points where the subject of the join point (method being executed in Spring AOP) has the given annotation

In the code presented above we have seen pointcut expressions combined with logical and (&&) operator. However, in Spring AOP, you can use three operators:

- && – logical and

-

– logical or - ! – logical not

Moreover, you can name your pointcuts, define them in one place and then use. We could refactor

MongoHealthAspectclass to reflect this:

@Aspect

@Component

@Order(0)

public class MongoHealthAspect {

private final HealthMetrics healthMetrics;

@Autowired

public MongoHealthAspect(final MetricRegistry registry, final TimerFactory timerFactory) {

healthMetrics = new HealthMetrics(registry, "adapters.db.mongo", timerFactory);

}

@Pointcut("execution(* org.springframework.data.mongodb.repository.MongoRepository.*(..))")

private void mongoRepositoryMethod() {}

@Pointcut(

"execution(* pl.allegro.rubicon.quoting.db.mongo.MongoCommonPriceListRepositoryCustom.*(..))")

private void customMongoRepositoryMethod() {}

@Around("mongoRepositoryMethod() || customMongoRepositoryMethod()")

@SuppressWarnings("all")

public Object aroundMongoDbCall(final ProceedingJoinPoint joinPoint) throws Throwable {

return healthMetrics.aroundCall(joinPoint);

}

}

Every advice method can declare an object of JoinPoint type as its first parameter. Note that around advice

uses ProceedingJoinPoint instead. Both JoinPoint and ProceedingJoinPoint provide many useful

methods such as (for a more detailed configuration please consult the documentation):

public interface JoinPoint {

// Returns the currently executing object.

// This will always be the same object as that matched by the <code>this</code>

// pointcut designator.

Object getThis();

// Returns the target object.

// This will always be the same object as that matched by the <code>target</code>

// pointcut designator.

Object getTarget();

// Returns the arguments at this join point.

Object[] getArgs();

// Returns the signature at the join point.

Signature getSignature();

}

ProceedingJoinPoint

public interface ProceedingJoinPoint extends JoinPoint {

public Object proceed() throws Throwable;

}

Shortcomings #

Aspect-oriented programming is, in fact, a double-edged sword. Separating cross-cutting concerns ensures that your code is in line with the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP). This means that your logic is distributed among business components, aspects and objects supporting aspects. As a result, it is more difficult to understand and maintain the code. Moreover, refactoring of the business code, for example renaming methods, may affect pointcuts and, in fact, disable them as they will match business method calls no more. However some IDEs, such as IntelliJ IDEA Ultimate, have a quite nice support for working with aspects and can handle refactoring of aspects properly. Debugging is another drawback of using aspects in the project. Aspect methods interweave with normal business flow and, as a result, it is difficult to understand what is going on in the program.

Summary #

This tutorial is an introduction to a much wider topic which is aspect-oriented programming. We have learned some of the basics here: what aspects are and how to use them in a Spring project. Every reader who wants to learn more is encouraged to follow the links from the Further reading section.