Transactions Aren’t Enough: The Need For End-To-End Thinking

Even the strongest safety properties implemented in today’s top databases are not enough to prevent data loss or corruption in all scenarios. We have learned to rely on mechanisms such as serializable ACID transactions, but they are not bulletproof.

Besides trivial cases, such as software bugs in our applications causing incorrect data to be written to the database, there might be more subtle issues. To illustrate them, let’s look at the following SQL transaction, which performs a budget reallocation between two departments:

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

UPDATE budgets

SET budget = budget - 1000

WHERE dept_name = 'A';

UPDATE budgets

SET budget = budget + 1000

WHERE dept_name = 'B';

COMMIT;

The ACID properties of a transaction (especially one running at a high isolation level) provide us with many useful guarantees. Atomicity means that either all of the transaction’s operations succeed or none do, and we won’t have to deal with partial results. Consistency ensures that all constraints, such as non-negative budget values, are preserved. Isolation guards against other parallel transactions interfering with the result. Durability gives us confidence that the performed budget reallocation will survive database restarts and crashes.

However, even all of that might not always be enough. A potential issue becomes apparent when we no longer focus just on the database’s perspective, but zoom out a little and consider our entire system.

Imagine an employee performing the above budget reallocation, but in an environment where the network isn’t stable. They initialize the operation by submitting a relevant form on the UI. Unfortunately, because of the unstable connection, the request eventually times out, and they see an error. In this situation, a natural reaction would be to simply retry the operation, but this can be problematic.

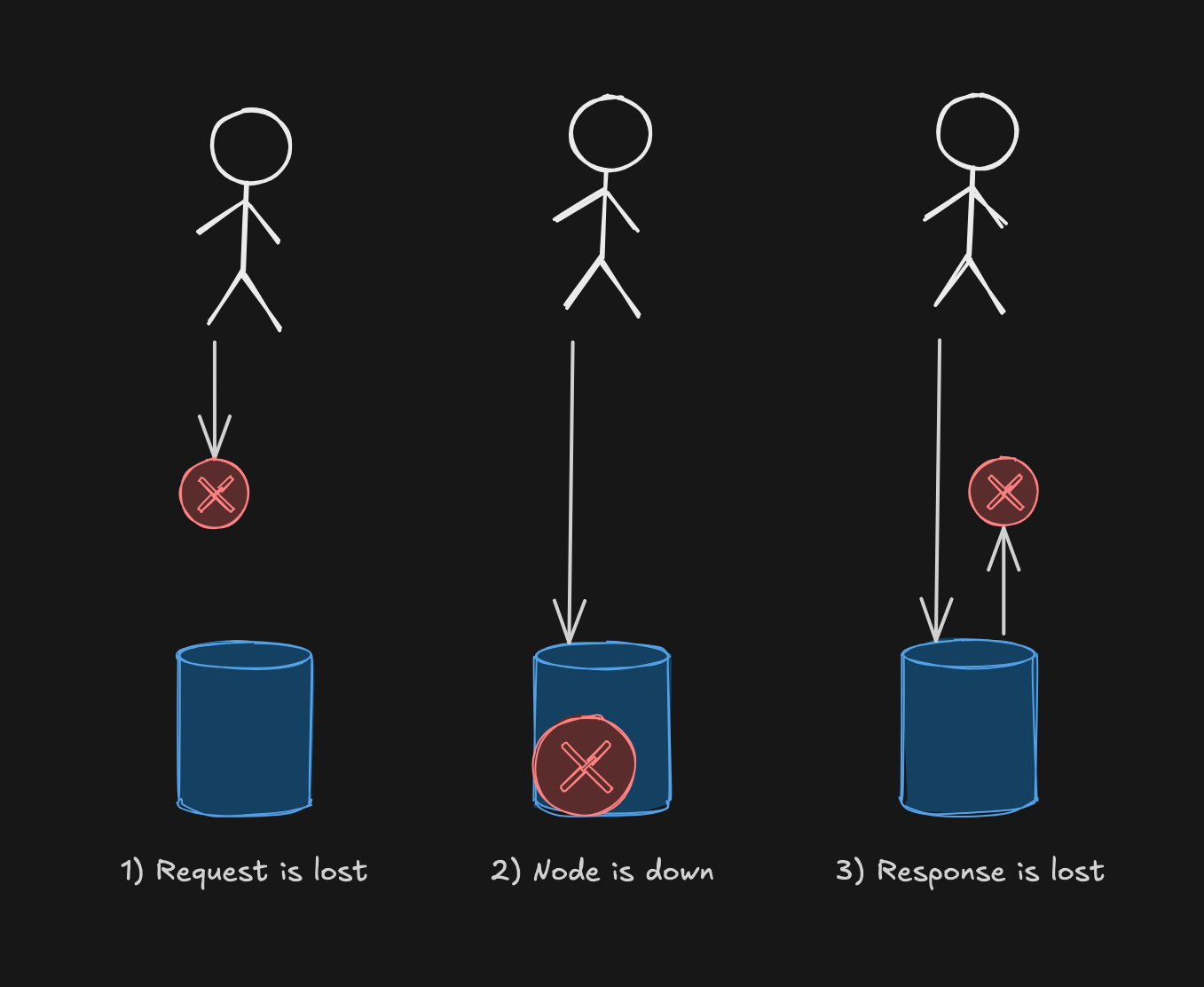

From the user’s perspective, it’s impossible to tell what really happened. Broadly, there are 3 potential cases, which you can see in the following diagram:

In the first two cases, when the request doesn’t even reach the server in the first place (perhaps due to misconfigured network, or the server being down), retrying isn’t harmful — it could result in the operation ultimately being handled.

The last case, however, is where the retry becomes dangerous. It might cause the operation to run a second time, transferring $2,000 instead of the intended $1,000 from one department to another. The database happily accepts the duplicate request because, from its perspective, it’s a completely separate transaction.

How can we solve this problem?

Effectively-Once Processing #

A guarantee we want to provide for our operation is effectively-once processing. It ensures that the final effect on the system is the same as if the operation was performed only once, even if in reality it could have been processed multiple times due to failures and retries.

One way to achieve this is to make the operation idempotent, meaning no matter how many times you execute it, the result stays the same. Some operations are naturally idempotent, like updating the last name of an employee, while others require a bit of additional effort, which is the case in our example.

To make the budget reallocation idempotent across the end-to-end flow of the request in our system, we could use operation identifiers. There are many ways to implement them. For instance, we could generate a unique identifier (such as a UUID) and include it in the client application as a hidden form field that is passed with every request. Alternatively, the identifier could be derived from a hash of all the relevant form values sent to the server. Both ways ensure that when the request is resubmitted, the ID stays the same.

The identifier would then be passed all the way through to the database, where we would make sure to process an operation with a given ID only once:

--Adding a uniqueness constraint

ALTER TABLE reallocations ADD UNIQUE (operation_id);

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

INSERT INTO

reallocations (operation_id, from_dept, to_dept, amount)

VALUES

('OPERATION_ID', 'A', 'B', 1000);

UPDATE budgets

SET budget = budget - 1000

WHERE dept_name = 'A';

UPDATE budgets

SET budget = budget + 1000

WHERE dept_name = 'B';

COMMIT;

In this example, we implement the effectively-once semantics by relying on the database’s uniqueness constraint on the operation_id field.

If we try to insert another budget reallocation with the same identifier, the transaction will be aborted, ensuring data integrity.

You could argue that we introduced some duplication with this change — the data about budgets is now stored in two tables: reallocations and budgets.

Notice, however, that we can now think of the reallocations table as a source of truth. It contains a complete log of all transfers we made between departments.

In this model, the budgets table acts as a derived view onto this log, which simplifies querying for a department’s current budget, but isn’t necessary.

We could always calculate the current value by scanning the reallocations table (assuming, for simplicity, that this is the only way to update budget values).

This approach also gives us new options.

For instance, if we can tolerate some delay in our application, the budgets table could be updated asynchronously, outside of the main transaction.

The current budget values could even be stored in a different storage system altogether, one tailored to specific querying needs.

This idea also happens to be the basis of the Event Sourcing approach.

Idempotency in Practice #

Operation identifiers aren’t limited to client requests. They can also prevent duplicate work in other areas, such as guaranteeing effectively-once message delivery or preventing unnecessary background job executions. At Allegro, for example, we use a similar approach when finalizing a checkout. When a user presses the “Buy and Pay” button, we use the checkout ID to record in the database that the operation is currently ongoing. If there was another request in the meantime for the same checkout, we would reject it with an appropriate status code to avoid initiating the entire post-purchase machinery twice.

Duplicate requests also create challenges with side effects, such as sending a confirmation e-mail to the user after a successful order payment. If you control the email-sending component, you can use operation identifiers to avoid sending duplicates. But if the component is a third-party service, we are dependent on them to provide idempotency features — there’s nothing we can do on our side if they don’t support it. That’s yet another reason to thoroughly evaluate all the alternatives when choosing external services.

As Pat Helland and Dave Campbell put it in the Building on Quicksand paper:

In practice, systems evolve to be idempotent as designers either anticipate the problem or make changes to fix it.

Summary #

While database transactions are a powerful tool for consistency, they only protect one part of our system. By thinking end-to-end and using simple patterns like operation identifiers, we can build fault-tolerant applications that are resilient to the inevitable failures of a distributed environment.

Going Further #

If you’re interested in the practical aspects of distributed systems, I recommend reading the Designing Data-Intensive Applications book, which goes deeper into the topic discussed above (and much more!) while maintaining an approachable and engaging style. Also, the references listed at the end of each chapter could easily keep you busy for a month if some of the concepts spark your curiosity.

Additionally, a second edition of the book is expected to be released in February 2026 (the first one is from 2017), which might make it a perfect time for you to pick up this book if you haven’t yet.