Automating the Cloud — hiding the complexity of hardware provisioning

Hardware is always hard. The amount of operations, maintenance and planning that goes into supporting a data center is a daunting challenge for any enterprise. Though often unseen, without hardware there is no software.

Although software seems to be a well defined domain with stable tools, practices and languages, hardware has had no such luck. That is why the complexities are often hidden. We try to hide networks, disks and IO, memory and CPU behind abstractions pretending that those are all reliable components.

That is also what Cloud computing promises. Resources available on demand, cheap, scalable and flexible The promise has its allure. Increasingly, companies are beginning in the Cloud, migrating, or utilizing the Cloud as a buffer for unexpected surges in traffic.

There is no doubt that Cloud and overall approach to hardware have matured in recent years, adopting practices that proved useful in software development. In this post I would like to explain how Allegro tries to manage Cloud and hide its inherent intricacies.

Infrastructure as Code #

The cornerstone of hardware management is a methodology called Infrastructure as Code. Long gone are the days of brave men and women that would roam data centers and manually install OS, plug cables into network interfaces and set up mainframes. Right now all those operations are still there but are abstracted away through a layer of standard components.

Thus, every component can be set up as a piece of code. Each IaC tool has its own unique set of strengths and weaknesses, and it is crucial for teams to carefully weigh these factors before adoption.

At Allegro we settled on Terraform. Code deploying infrastructure has to be versioned, reviewed and then executed. We also use a set of standard modules that enforce consistent setup. However, not everyone is a Cloud Engineer and not everyone has to be. That is why we created yet another layer of abstraction that aims at simplifying IaC even further.

The Requirements #

We did that because our audience are Data Scientists and Data Analysts. People who, although they make heavy use of Cloud, should be insulated from the complexities of its tools. Their day to day work focuses on finding new insights in the data and feeding them to the organization to help make the correct decisions.

Knowing that, we had a simple requirement. Streamline creation of Cloud infrastructure that is needed to analyse and process large volumes of data.

To assure eager adoption, we needed to establish a set of standard tools, permissions, and practices that would be widely used among data analytics teams, and so we created an architecture that would support any current or future needs.

The Solution #

The solution consists of four components:

- DSL

- Terraform modules

- Artifact

- Runtime

DSL #

We created a simple Domain Specific Language that aims at hiding any Cloud provider under common conventions. This is what our production configuration looks like:

infrastructure:

gcp:

schedulers:

- name: my-team-composer

version: v2

parameters:

airflow_config_overrides:

email-email_backend: airflow.utils.email.send_email_smtp

smtp-smtp_host: "smtp.gateway.my.domain"

smtp-smtp_mail_from: "my-team@allegro.pl"

smtp-smtp_starttls: False

smtp-smtp_user: ""

pypi_packages:

jira: "==2.0.0"

google-api-core: "==1.31.5"

oauthlib: "==3.1.0"

allegro-composer-extras: "==2.0.0rc8"

processing_clusters: ~

Though the simplest possible configuration would look as follows:

infrastructure:

gcp:

schedulers:

- name: my-team-composer

In the background this gets translated into Terraform code that uses our custom modules and defaults. Advanced users are not constrained since we also allow for pure Terraform code instead of our DSL. One has to choose freedom and maintenance cost over defaults and ease of getting started.

Artifact #

Once the IaC gets reviewed and accepted, whether DSL or Terraform, it gets packaged into an artifact. The artifact is an immutable, versioned archive that contains infrastructure’s definition. We prevent manual changes by revoking permissions in the the Cloud. This means that we have a controlled and auditable environment. An added bonus is that we can easily roll back to the previous version should the change prove wrong.

Internally, the artifact is a simple zip archive that can be extracted and inspected by hand to see whether it really contains what we expect.

unzip artifact.zip

Archive: artifact.zip

creating: infrastructure/

creating: infrastructure/prod/

inflating: infrastructure/prod/main.yaml

inflating: infrastructure/prod/data-engine-backend.tf

inflating: infrastructure/prod/main.tf

inflating: infrastructure/prod/output.tf

creating: infrastructure/test/

inflating: infrastructure/test/main.yaml

inflating: infrastructure/test/data-engine-backend.tf

inflating: infrastructure/test/main.tf

inflating: infrastructure/test/output.tf

creating: infrastructure/dev/

inflating: infrastructure/dev/main.yaml

inflating: infrastructure/dev/data-engine-backend.tf

inflating: infrastructure/dev/main.tf

inflating: infrastructure/dev/output.tf

inflating: tycho.yaml

inflating: metadata.yaml

Terraform modules #

We wrap and repackage external Terraform modules. We do that to provide sane defaults and create conventions that will be consistent across the entire organisation. We also provide libraries that integrate with these conventions so that users can use advanced functionalities without thinking about setup choices. They just work.

Runtime #

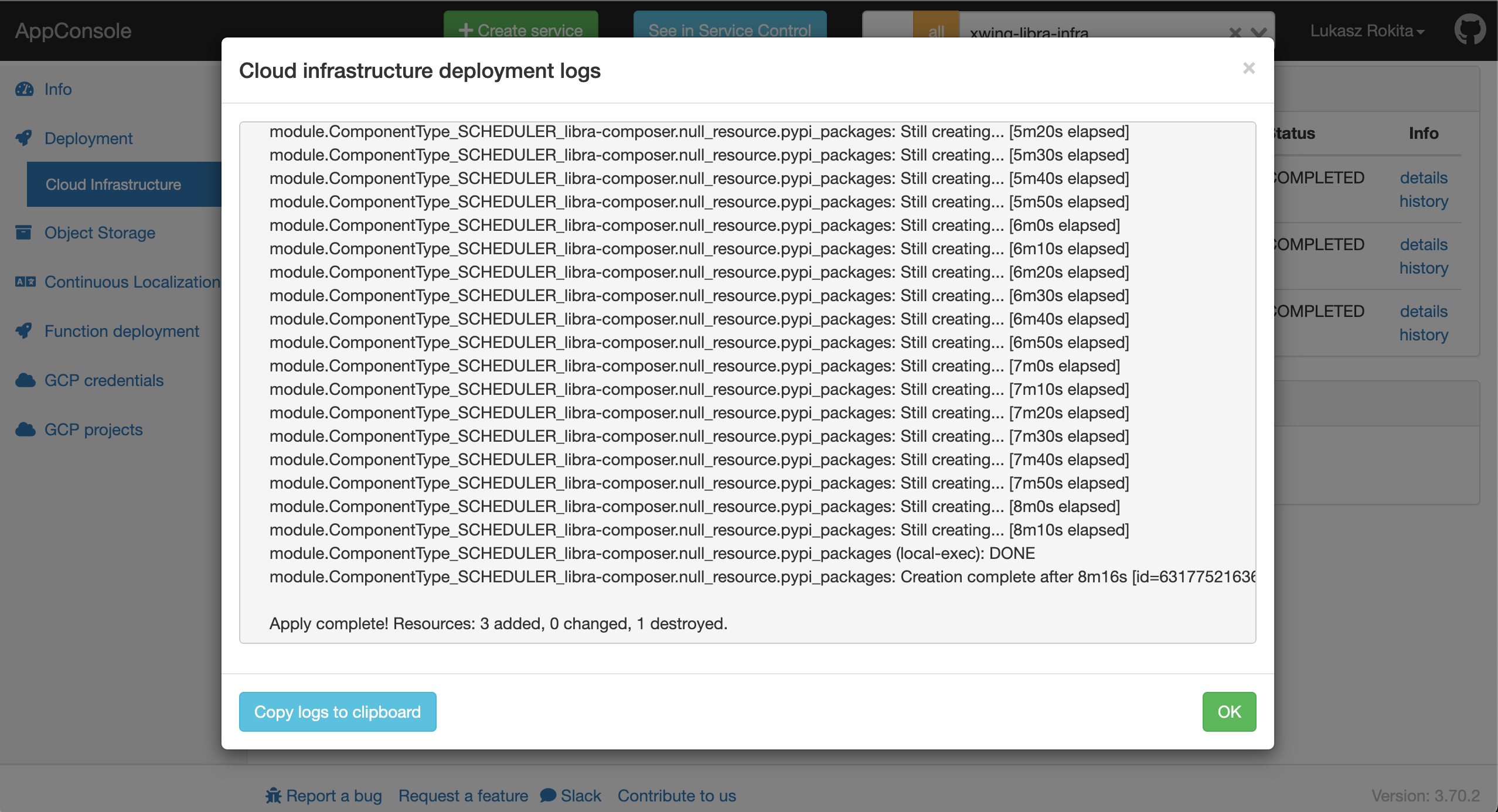

At runtime the user has to go to their infrastructure project, choose which infrastructure version they would like to deploy and observe the changes as they are executed live, in the Cloud. This is what it looks like:

Under the hood a K8s job is created which uses a dedicated Docker runtime that helps us control environment versions and the overall process. This image is also quite useful for debugging and development. Since we have access to the artifact and runtime environment the work is easy and done comfortably on our own machine.

K8s jobs have another useful feature - they are independent. We have a guaranteed stable environment that gets provisioned and cleaned up on demand and is separated from other jobs. The orchestration is automated and supervised so that users need not think about installing Docker, Terraform or any other tool that would otherwise be required and we have the freedom to change the process (provided that we stay compatible).

The Good #

From my point of view the good parts are what every engineer likes about a solution.

- Ease of use

- Extendability

- Clean and repeatable deployments

- Observability and debuggability

We achieved that by packaging the deployment into a couple of simple, decoupled steps. We based the solution on an existing process for microservices, which should already look familiar to everyone at Allegro. We provide extensive documentation, support for all people that use our deployment process, and try to exhaustively test every change so that users can focus on what’s important in their day to day tasks and think of Cloud as just another data center.

The Bad #

There is no free lunch and that is also the case with provisioning infrastructure. Although we did our best to create a coherent and enjoyable environment there are shortcomings that could not be eliminated.

We need to acknowledge that Cloud is as fickle as the wind. Though everyone does their best to navigate its torrents, there is no question that we can’t completely hide the hardware. Thus we sometimes land on an island of incoherent state. Occasionally, the automatic processes fail to apply changes. The runtime thinks that the infrastructure should look different than it is actually provisioned, reports that it can’t reconcile the state automatically and fails. This requires manual intervention which always worsens the user experience.

At the end of the day Cloud uses different primitives than software does and Infrastructure as Code can’t address that. You don’t have atomic operations so provisioning a service can fail or land in an unknown state. You also can’t run unit tests for infrastructure without actually running a deployment. In essence you have a Schrödingers Cloud - you won’t be sure what will happen until you execute your change. This contrasts with all that we know and came to love about software which we try to test in all possible scenarios.

Conclusion #

Our migration to Cloud is an ongoing process. This may be a never ending challenge as both Cloud and our organization evolve. We needed to create a whole new environment that would be both flexible and invisible to the users. By using some simple patterns and tools we encapsulated infrastructure provisioning in components used for microservices. Additionally these components are testable and extendable which helps adapt to changes and users’ feedback.

At the moment of writing this the solution has been running in production for six months. More than one thousand deployments have been made to production and countless more to dev and test.

I hope this post will spark your creativity and inspire new ways of thinking about Cloud provisioning.