Visual thinking

We use written (source code) language to express our intentions in a machine-readable form. We use spoken language to communicate with other people. We pride ourselves as ones choosing a programming language optimized to the task at hand. Do we use the optimal way to express our ideas?

The Story #

Spoken planning #

— Josh, could you summarize what we are going to implement, please?

That was a bit unexpected. He was just trying to match what he already knew from onboarding days with what was just said. It was really difficult to follow team discussion at the same time. It was a standard planning session, held over Zoom, with his distributed team. Someone was already sharing their screen and the story summary, along with acceptance criteria, was visible. They were developing an online store and the current topic was: basket price reduction for active users. In short: users who spent more than 50€ for the last 7 days should have a discount applied during the checkout process.

— Well, we are going to add a new service which is going to hold this discount logic. We will provide an API for the

cart service to call us and we will check the transactions store for recent orders.

— Is that all?

— I didn’t catch more changes.

— What about customers willing to check if they are eligible for a discount?

— Oh, so it seems we need to change the “My Account” page as well.

— And the checkout service? We have to both display discount and use it.

— You’re right! I was trying to picture the main change in my mind and wasn’t paying attention to the whole

discussion.

— Guys, checkout stays the same. The cart is providing everything the checkout requires.

Retrospective #

Let’s stop here for a moment. Have you ever been in a situation, when you were forced to do two things at the same time? For example, listening to what is being said and trying to actively participate in the discussion regarding a not exactly well-known topic? Was it a demanding experience? I had such an opportunity and I remember these sessions as quite demanding. Usually, after an hourly session, I was exhausted and in need of a break. Not to mention that it required a significant amount of writing to capture everything that was said — just to have an option of referring back to this during the sprint. What if this session looked differently?

Visual planning #

— Josh, could you summarize what we are going to implement, please?

That was a bit unexpected, however, it was a no-brainer.

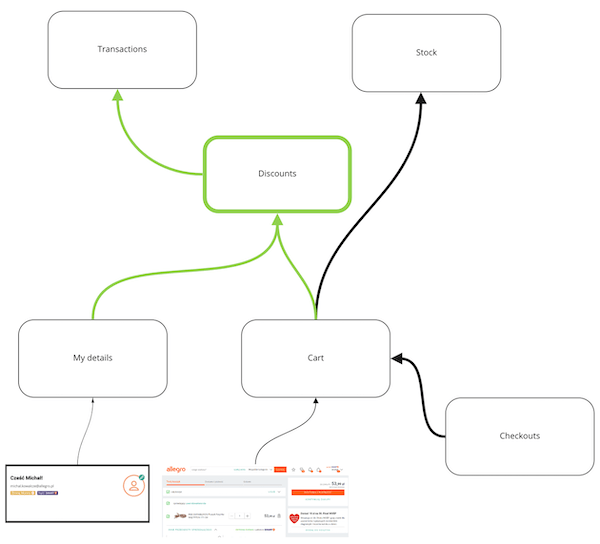

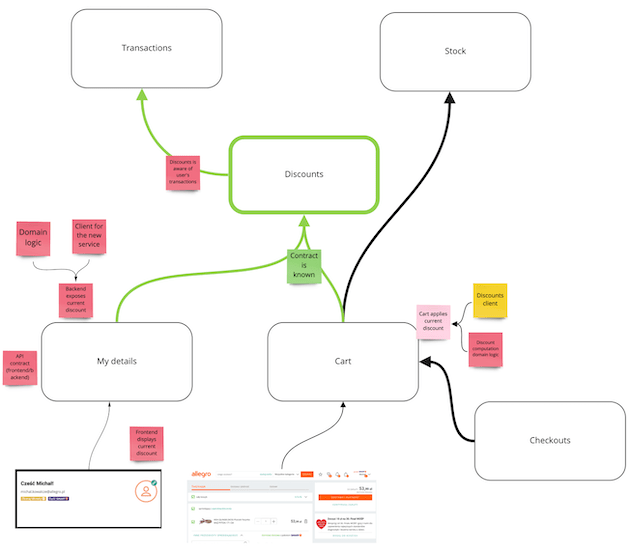

“As we can see in the picture we are going to add a new service, discounts. This service will be called by the current

cart service to display a reduced price (if applicable). Also, the “My Account” page is going to call us to retrieve the

current rebate for the logged user”.

“As we can see in the picture we are going to add a new service, discounts. This service will be called by the current

cart service to display a reduced price (if applicable). Also, the “My Account” page is going to call us to retrieve the

current rebate for the logged user”.

The difference #

What is the main difference between the first scenario and the second one? To me, it is about a common model. In the first case, I am building an individual model of a change. I need a significant amount of energy to translate speech to my model and to explain my model to others. What is more — everyone involved in the discussion is building a mental model on their own with a similar amount of energy spent on synchronization.

In the case of the second scenario, the model is shared. There is no need to maintain private models. It is easy to understand changed elements and to refer to discussed changes later. “A picture is worth a thousand words” after all.

Output from a visual planning is something that can be used further during a sprint. Depending on the tool it is possible to use it instead of an issue-tracking tool. Sticky notes can indicate actions, tasks, TODOs. They can be arranged in a tree and display the scope of a pull request. They can be connected by a dotted line to indicate dependencies. And in the worst case, when you do not have any idea how to visualize something, you can always use a block of text and describe it using words.

The background #

Why switching to a drawing board has such an effect? To answer this question we have to check some facts.

On a daily basis, a spoken (or written) language is our standard way of communication. Children, however, need some time to develop such a skill. Earlier they are able to:

- register movement (at 2 months of age)

- try to grab things by hand (5 months)

- follow movement with their eyes, find hidden things (7 months)

- exploit cause-effect — drop a toy and watch it fall (8 months)

- start to use words in a proper context (11 months)

Such spatial skills are something all creatures need to develop to survive. Even plants, to some extent, exhibit spatial-aware behavior — they move to follow the sun.

It is worth noting that spatial-related terms like “where, here, near, etc.” can be translated to any language in the world.

On the other hand, what language do we use to express ideas-related actions? As Barbara Tversky listed in her “Mind in motion” lecture we can:

- raise ideas

- pull them together

- tear apart

- turn inside out

- push forward

- toss out

We talk about ideas in the same way as about any space-related topic!

How could it happen? Scientists have been trying to understand the functions of different parts of the brain for some time already. In the seventies, they have identified the so-called place cells — neurons that are activated at a specific location. It took some time to identify another layer of neurons on top of these: grid cells, working as our inner GPS, activated when switching locations. The latter discovery was awarded a Nobel Prize in 2014.

Tests on human beings resulted in another finding: place cells are activated not only in specific locations. They are also activated by events, people, ideas. The grid cells are activated by thinking about the consequences of events, by social interactions, and by connecting ideas together. We are using the same brain structures for spatial orientation, for ideas, and for social interactions. This is the reason why Barbara Tversky issued an audacious thesis that “all thoughts begin as spatial thoughts”.

Map elements #

Nowadays we have a GPS sensor in almost any smartphone, so it is rather difficult to get lost. Basic GPS information - current coordinate — is not very useful by itself. It is much more convenient to display our current location over a map layer. What is a map? According to wikipedia, it is “[..] a symbolic depiction emphasizing relationships between elements of some space [..]”.

As our ideas — and imaginary concepts like services — are treated by our brains as spatial elements we simply use known concepts of space visualization to present imagined beings and relations among them.

Arrows #

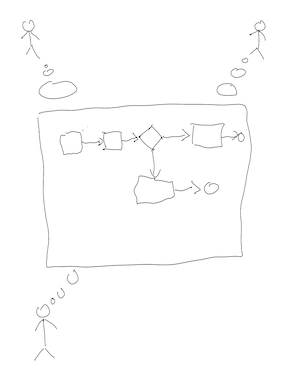

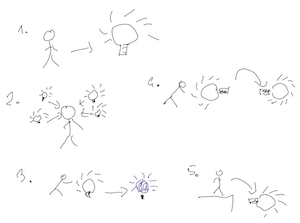

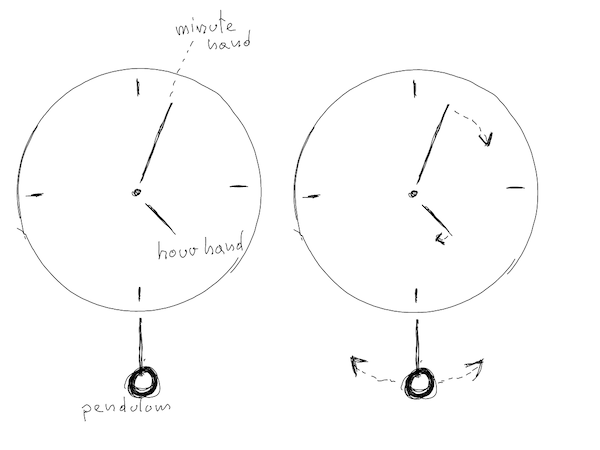

So far we used several symbols in our planning diagrams. Almost all of them can be found in maps as well, except one. This element is an arrow — a significant element of our drawings. According to Barbara Tversky in the already mentioned “Mind in motion” lecture arrows as visual elements started to appear in the 20th century. Before that symbols of feet or fingers had been used to indicate direction. The addition of arrows changes our perception of diagrams: without them, it is usually a structural drawing, that requires additional labels to understand. Arrows transform such a structural diagram into a functional diagram: we can trace arrows to their origin, we see how things are connected and how they cooperate. Check the example below — the left-hand side version is static, only describes elements and the right-hand side version shows the movement of particular elements without using a single word.

Messy lines #

All these well-known elements are our means of communication with other people, or even ourselves, at a different point in time. Sometimes we draw to discover, we sketch shapes to find inspiration, an idea. This seems to be important in a different creative profession: architecture. Architects discover ideas in sketches. The ambiguity of non-obvious shapes promotes creativity. It is so important in this profession that sketches from private collections are sold as books. One of such books is Sou Fujimoto sketchbook. I would like to leave you with one quote from it, found at “Drawing for Discovery” post:

The lines are never certain, never knowing where the next will lead to. Never knowing, but continuing to draw. And for this very reason, there is always an opportunity for something new. From the infinite dialogues of the brain, eyes, hand, paper, and space, new architecture is born.