How to ruin your Elasticsearch performance — Part I: Know your enemy

It’s easy to find resources about improving Elasticsearch performance, but what if you wanted to reduce it? This is Part I of a two-post series, and will present some ES internals. In Part II we’ll deduce from them a collection of select tips which can help you ruin your ES performance in no time. Most should also be applicable to Solr, raw Lucene, or, for that matter, to any other full-text search engine as well.

Surprisingly, a number of people seem to have discovered these tactics already, and you may even find some of them used in your own production code.

Know your enemy, know your battlefield #

In order to deal a truly devastating blow to Elastic’s performance, we first need to understand what goes on under the hood. Since full-text search is a complex topic, consider this introduction both simplified and incomplete.

Index and document contents #

In most full-text search engines data is split into two separate areas: the index, which makes it possible to find documents (represented by some sort of document ID) matching specified criteria, and document storage which makes it possible to retrieve the contents (values of all fields) of a document with specified ID. This distinction improves performance, since usually document IDs will appear multiple times in the index, and it would not make much sense to duplicate all document contents. IDs can also fit into fixed-width fields which makes managing certain data structures easier. This separation also enables further space savings: it is possible to specify that certain fields will never be searched, and therefore do not need to be in the index, while others might never need to be returned in search results and thus can be omitted from document storage.

For certain operations it may be necessary to store field values within the index itself, which is yet another approach.

Inverted index #

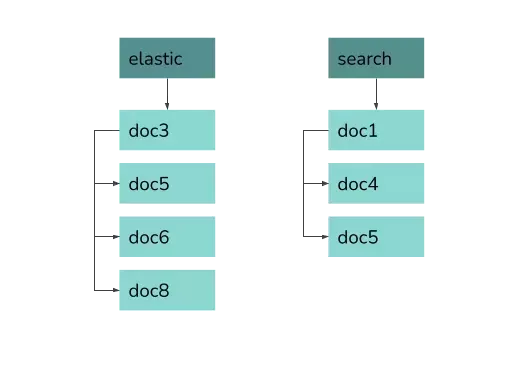

The basic data structure full-text search uses is the inverted index. Basically, it is a map from keywords to sorted lists of document IDs, so-called postings lists. The specific data structures used to implement this mapping are many, but are not relevant here. What matters is that for a single-word query this index can find matching documents very fast: it actually contains a ready-to-use answer. The same structure can, of course, be used not only for words: in a numeric index, for example, we may have a ready-to-use list with IDs of documents containing the value 123 in a specific field.

Indexing #

The mechanism for finding all documents containing a single word, described above, is very neat, but it can be so fast and simple only because there is a ready answer for our query in the index. However, in order for it to end up in there, ES needs to perform a rather complex operation called indexing. We won’t get into the details here, but suffice to say this process is both complex when it comes to the logic it implements, and resource-intensive, since it requires information about all documents to be gathered in a single place.

This has far-reaching consequences. Adding a new document, which may contain hundreds or thousands of words, to the index, would mean that hundreds or thousands of postings lists would have to be updated. This would be prohibitively expensive in terms of performance. Therefore, full-text search engines usually employ a different strategy: once built, an index is effectively immutable. When documents are added, removed, or modified, a new tiny index containing just the changes is created. At query time, results from the main and the incremental indices are merged. Any number of these incremental indices, called segments in Elastic jargon, can be created, but the cost of merging results at search time grows quickly with their number. Therefore, a special process of segment merging must be present in order to ensure that the number of segments (and thus also search latency) does not get out of control. This, obviously, further increases complexity of the whole system.

Operations on postings lists #

So far we talked about the relatively simple case of searching for documents matching a single search term. But what if we wanted to find documents containing multiple search terms? This is where Elastic needs to combine several postings lists into a single one. Interestingly, the same issue arises even for a single search term if your index has multiple segments.

A postings list represents a set of document IDs, and most ways of matching documents to search terms correspond to boolean operations on those sets.

For example, finding documents which contain both term1 and term2 corresponds to the logical operation set1 AND set2 (intersection of sets) where

set1 and set2 are the sets of documents matching individual search terms. Likewise, finding documents containing any word out of several corresponds

to the logical OR operation (sum of sets) and documents which contain one term, but do not contain another, correspond to AND NOT operator (difference

of sets).

There are many ways these operations can be implemented in practice, with search engines using lots of optimizations. However, some constraints on the complexity remain. Let’s take a look at one possible implementation and see what conclusions can be drawn.

While the operations described below can be generalized to work on multiple lists at once, for simplicity we’ll just discuss operations which are binary, i.e. which take two arguments. Conclusions remain the same for higher arity.

In the algorithms below, we’ll assume each postings list is an actual list of integers (doc IDs), sorted in ascending order, and that their sizes are n and m.

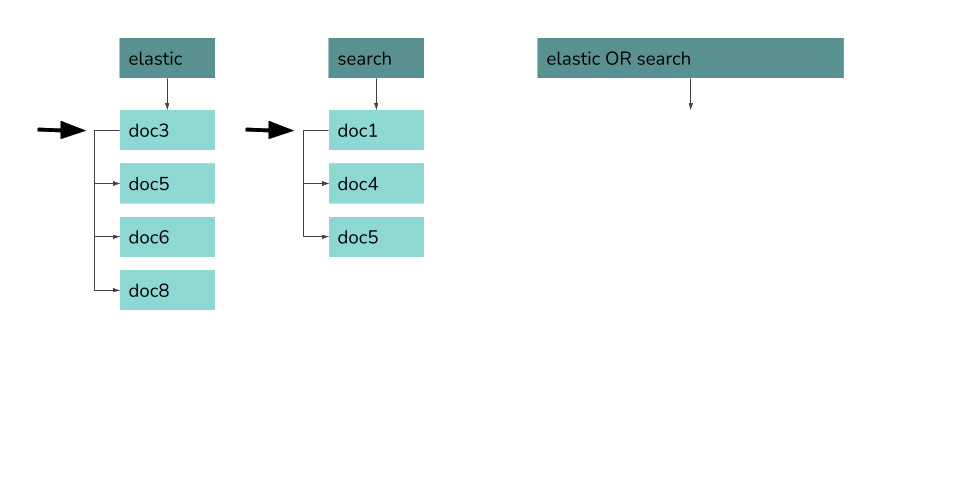

OR #

The way to merge two sorted lists in an OR operation is straightforward (and it is also the reason for the lists to be sorted in the first place). For each list we need to keep a pointer which will indicate the current position. Both pointers start at the beginning of their corresponding lists. In each step we compare the values (integer IDs) indicated by the pointers, and add the smaller one to the result list. Then, we move that pointer forward. If the values are equal, we add the value to the result just once and move both pointers. When one pointer reaches the end of its list, we copy the remainder of the second list to the end of result list, and we’re done. Like each of the input lists, the result is a sorted list without duplicates.

If you are familiar with merge sort, you will notice that this algorithm corresponds to its merge phase.

Since the result is a sum of the two sets, its size is at least max(m, n) (in the case one set is a subset of the other) and at most m + n (in the case the two sets are disjoint). Due to the fact that the cursor has to go through all entries in each of the lists, the algorithm’s complexity is O(n+m). Even for any other algorithm, since the size of the result list may reach m + n, and we have to generate that list, complexity of O(n+m) is expected.

The result does not depend on the order of lists (OR operation is symmetric), and performance is not (much) affected by it, either.

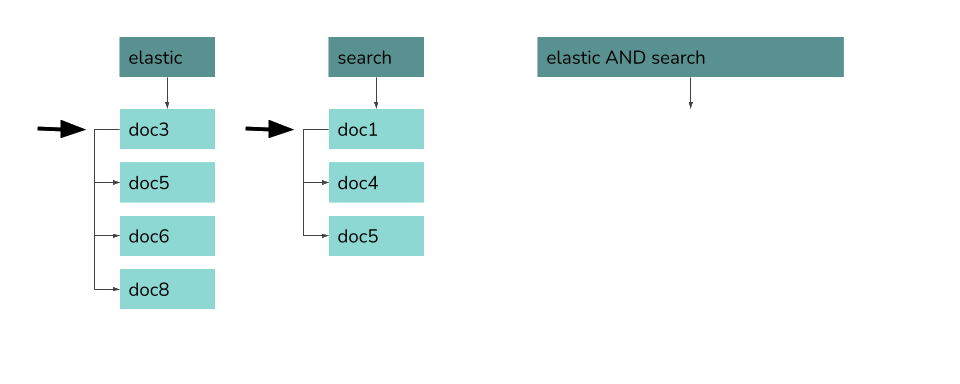

AND and AND NOT #

Calculating the intersection of two sets (what corresponds to the logical AND operator) or their difference (AND NOT) are very similar operations. Just as when calculating the sum of sets, we need to maintain two pointers, one for each list. In each step of the iteration we look at the current value in the first list and then try to find that value in the second list, starting from the second list’s pointer’s position. If we find the value, we add it to the result list, and move the second list’s pointer to the corresponding position. If the value can’t be found, we advance the pointer to the first item after which the searched-for value would be. Once the second list’s pointer reaches the end, we are done.

The algorithmic complexity of these two operations differs quite a bit from that of OR operation. First of all, a new sub-operation of searching for a value in the second list is used. It can be implemented in a number of ways depending on the data structures (flat array, skip list, various trees, etc.). For a simple sorted list stored in an array, we could use binary search whose complexity is O(log(m)). Things get a little more complicated since we only search starting from current position rather than from the beginning, but let’s skim over this for now. What matters is that we perform a search in the second list for each item from the first one: the complexity is no longer symmetric between the two lists. If we change the order of the lists, the result of AND operation does not change, but the cost of performing the calculation does. It pays to have the shorter of the two list as the first in order, and the difference can be huge. The cost also depends very much on the data, i.e. how big the intersection of the two lists is. If the intersection is empty, even looking for the first list’s first element in the second list will move the second list’s pointer to the end, and the algorithm will finish very quickly. The upper limit on the size of the result list (which in turn puts a lower limit on algorithmic complexity) is min(m, n).

If we’re performing the AND NOT rather than AND operation, the match condition has to be reversed from found to not found. While the result changes when we exchange the two lists, algorithmic properties are the same as for AND, especially the asymmetry in how the first and second list’s size affects the computational cost.

In order to improve performance, many search engines will automatically change the order in which operations are evaluated if it does not alter the end result. This is an example of query rewriting. In particular, Lucene (and thus also Elasticsearch and Solr) reorder lists passed to AND operator so that they are sorted by length in ascending order.

Beyond the basics #

There are lots of factors which affect Elasticsearch performance and can be exploited in order to make that performance worse, and which I haven’t mentioned here. These include scoring, phrase search, run-time scripting, sharding and replication, hardware, and disk vs memory access just to name a few. There are also lots of minor quirks which are too numerous to list here. Given that you can extend ES with custom plugins that can execute arbitrary code, the opportunities for breaking things are endless.

On the other hand, search engines employ a number of optimizations which may counter some of our efforts at achieving low performance.

Then again, some of these optimizations may themselves lead to surprising results. For example, often there are two different ways of performing a task, and a heuristic is used to choose one or the other. Such heuristics are often simple threshold values: for example, if the number of sub-clauses in a query is above 16, it will not be cached. Likewise, certain pieces of data may be represented as lists and then suddenly switch to a bitset representation. Such behaviors may be confusing since they make performance analysis more difficult.

Anyway, even the basic knowledge presented above should allow you to deal some heavy damage to your search performance, so let’s get started.

Summary #

I hope the first part of this post gave you some background on how Elastic works under the hood. In Part II, we’ll look at how to apply this knowledge in practice to making Elasticsearch performance as bad as possible.