Implement stateless authentication like a pro using OAuth: A 100% correct approach

Many of us spend most of their software development careers improving and extending applications protected by pre-existing security mechanisms. That’s why we rarely address problems related directly to authentication and authorization unless we build apps from scratch. Regardless of your experience I still hope you will find this article interesting. It’s not meant to be a tutorial. I would like to focus on clarifying basic concepts and highlighting common misconceptions.

Alpha disclaimer: #

Sorry to disappoint you, but the title of this article is just a cheap click-bait. It doesn’t matter whether you started reading because you disagree with the title or because you hoped to find the holy grail of securing web applications. There is a chance you will find something for yourself anyway.

Beta disclaimer: #

This post is not meant to answer the “how does the login with Facebook work“ question. We will spend some time on it, but just to provoke a discussion, not to go through a tutorial.

Gamma disclaimer: #

I have never built a full-fledged auth process from scratch myself in a commercial web app. I’m no security expert, so you read at your own risk.

Authentication vs Authorization #

Wow! If you are still reading, cool! Let’s start with a short recap on these two basic concepts. Authentication is about verifying who you are. You need to prove your identity, that’s all. You may authenticate, for example, by using a password or your fingerprint. You may need to use a token (hard or soft), an authentication-app-generated code or a text message sent to your phone number. I hope you tend to use at least two of these. Anyway, once you’ve done it, you are in.

Authorization is about verifying what you are allowed to do. I’m not going to copy-paste bookish definitions here. For example, when entering a university library, you authenticate by presenting your ID. The librarian checks the authenticity of the document and analyzes whether you are the one on the photograph or not. The authorization process starts right away. To keep things simple, the librarian checks, based on your confirmed identity, whether you are a professor or a student. This implies which books you can borrow and how many you can take home. This is where the privileges or permissions come into play.

If you are already bored with the most obvious meme I could use, let me give you another obvious example of authorization. When entering a military zone, you also present your ID for authentication. You can’t get in unless you ARE, e.g. a military officer. It’s not the authentication that failed then. The guardian knows who you are now. You are forbidden to enter as you have not been granted such an authority.

One last meme, I promise.

OAuth 2.0: why is it not about authenticating the user? #

I started with the above trivia because the concepts of authorization and authentication are mingled so often that, even when you know them, you may still get a headache when reading about OAuth (from now on, I will omit the 2.0 specification version).

What is OAuth? I hate copy-pasting definitions from official docs and other blogs. What I hate even more is copy-pasting them, rephrasing and selling as my own. So, unless you already did, please stop reading and check out the docs, this website and then the auth0 website. If you liked the latter, you may also check out their blog in general. I assume you’ve read the suggested docs so I will move on to using the traditional OAuth lingo (grants, flows, resources, third-party servers etc).

OAuth flows revisited #

The OAuth specification describes this framework as available in four flavours:

- Authorization Code

- Implicit

- Resource Owner Credentials

- Client Credentials

So 2012.

The Resource Owner Credentials (User Credentials) flow is already legacy and officially banned by IETF. The latest OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practice disallows the password grant entirely.

The same applies to the Implicit flow, also discouraged in its original form. Some experts analyze whether it is already dead or not. In the following two “login with..“ examples you should understand OAuth as limited to the Authorization Code grant. The Client Credentials grant is a completely different story, handled in a further part of the article.

It’s Hello World Time #

I prefer to think of OAuth as a set of guidelines and best practices that help you solve a common problem related to authorization, as opposed to a strict framework or protocol. This common problem may be for instance the following. Damn, how the hell did these guys implement the cool log in with Facebook feature in their app (not so cool anymore, let’s be honest it’s 2021 not 2015). Let’s call this app fb64.com . To be precise, how did those guys use the Facebook API to delegate the process of asking the user whether or not fb64.com can access some of their Facebook account data? You may find an analogous scenario described in virtually EVERY SINGLE blog post referring to OAuth, but there is a good reason why I do it here too. I use it because it sucks and introduces misunderstandigs regarding real-life delegated authorization and log in with a third party identity provider scenarios. Let’s consider the dumbest example ever.

- The resource is your Facebook wall and everything you’ve posted on it.

- The resource owner is, well, just you.

- The resource server is Facebook.

- The client is the fb64.com app. Its cool feature is presenting your 10 recent posts as Base64 encoded strings.

- The authorization server is also Facebook itself.

So, in the above scenario, you get the cool feature without giving these guys your Facebook login and password. When you are redirected to the Facebook login page first you give your consent for fb64.com to access a specific subset of your profile data. Next you type in your credentials (you send them to facebook.com, not to fb64.com) and when you get redirected back to fb64.com you are already logged-in and see an awesome black-and-white website with your Base64 encoded posts.

What have you done? You’ve granted some client app access to your protected resource data without sharing your credentials with it. Full stop.

But is that what we meant? Is that the kind of resource sharing and delegated authorization you expect when you want to, for example, log in to Booking, via Facebook, to book a hotel room but don’t want to set up an account?

It’s Real Life Scenario Time #

Let’s come up with a more real-life-ish scenario. When you choose a third party identity provider login you probably expect to get an account without wasting time to sign-up and come up with Yet Another Password. Before you click continue as John Smith you are assured that:

- what the website will have access to are your name, surname, email and profile picture,

- it will not be allowed to post on your wall.

So what is the resource you are granting some app access to? Your identity! You use Facebook to let Booking know your name, surname, email and picture. Obviously, in the meantime, Facebook needs to check and confirm that you are who you say you are, e.g. john.smith@somemail.com. So sharing your identity, which is the actual resource you are authorizing booking.com to access, implies being authenticated behind the scenes. Proving your identity is authentication while sharing it is authorization.

Digression: #

Seriously, how often do people use and authorize post, tweet or photo importing apps? Apps that post to your wall? I cannot name even one. Importing contacts from Gmail or one social network while logging in to another social network is the only everyday use case I can think of, apart from identity resource sharing.

OAuth based “authentication“ #

OAuth does not say a word about the way the authorization server should authenticate the user before letting them authorize the client app. How does OAuth help in authenticating the user then? It doesn’t! The authentication happens transparently to the client app, sort of in-between the ongoing authorization process. It depends on the authorization server’s internal authentication implementation. When you get redirected to Facebook and you type in your email and password and hit enter, it could even trigger basic authentication underneath and send your Base64 encoded plain-text credentials in the Authorization (sic!) HTTP header. Or it could trigger a three factor authentication process including a hard token and a magic link sent to your email. Never forget that OAuth is an authorization framework when you go to job interviews.

First, get in #

Why do we say that we log in to Booking with Facebook using OAuth? I guess the reason of one of the common misunderstandings regarding the purpose of the framework is just this unfortunate mental shortcut. And the fact that most of us think log in === authenticate (which is not wrong, I refuse to elaborate on the semantics in this case). We should rather say that we authorize Booking to delegate authentication to Facebook and use the confirmed identity, in the background of logging in to Booking. We do all that instead of logging in to Booking directly. I guess it’s just too long and convoluted ;).

Then, stay inside #

I can’t stress this enough: OAuth based authorization implies authentication performed by the authorization server. But to keep you logged in, the client app needs to use some other mechanism underneath, e.g. HTTP session based on cookies. That’s another blank spot on the OAuth map. Which is not wrong, it’s just not the concern of this framework. Just, please, don’t use the access token as a session ID.

Authorizer and authorizee ;) #

You build the sign-in layer of your app using OAuth as the authorization framework. The user gets authenticated by the third party and allows your app to access their identity data. Let’s clarify another common misconception related to the part OAuth plays here. Who is the one being authorized? The user? No, it’s your app. The client app is being authorized - by the user - to access a resource, via the authorization server. Does that imply authorizing the user, too? Yes, it may when you think of it the other way round. You cannot authorize the client app to do something that you are not yourself authorized to do in the resource server. This is where access token scopes grow out of resource owner privileges, permissions, roles etc. Can the shared identity resource also contain some permissions and privileges granted to the user within the authorization server? Yes, they can and they often do, e.g. as a permissions or roles field in the access token returned by the authorization server. I specifically think of Json Web Tokens and their custom claims. Forgive me for not pasting in an example of a JWT, but I’m allergic to pasting things you have probably seen a hundred times elsewhere.

OAuth based authentication (no quotes) #

Yep, here 100% correct approach is not just a clickbait title.

A corresponding authentication framework which you can use to implement the identity layer of your application is Open ID Connect.

While the purpose of OAuth is Delegated Authorization, what describes OpenID Connect best is Federated Identity Management. What does it mean?

OK, I lied. Brace yourselves, for a citation is coming:

While OAuth 2.0 is about resource access and sharing, OIDC is all about user authentication. Its purpose is to give you one login for multiple sites. Each time you need to log in to a website using OIDC, you are redirected to your OpenID site where you login, and then taken back to the website.

I guess you’ve just said: “Wait, wait, whaaat???“

… you are redirected to your OpenID site where you login, and then taken back to the website

Now you may think: “We’ve just gone through that, haven’t we? You’ve just swapped one framework for another to make the post longer.“

No, it’s just that OIDC is not loosely based on OAuth, it’s actually plugged into it, filling all the authentication gaps we’ve mentioned before. It’s best suited to develop your own Identity Provider or more likely an internal security component of a system you are building. It may also be a universal login and authorization service for a broader environment of applications and systems in your or your client’s company. We will not dig deeper into OIDC in this post, as it deserves a post of its own. The fact that OIDC perfectly fits into OAuth is best illustrated by the following. While OAuth lets you control access to given resources (like user identity) by issuing either JWT access tokens or UUID access tokens, OIDC handles user identity with ID tokens. Access tokens are opaque from the client’s perspective. ID tokens MUST be a JWT user identity state representation because the ID token, unlike the access token, is readable for the client. OIDC does all what was behind the scenes and depending on the identity provider implementation.

Client authentication #

The biggest lie in OAuth is that it has nothing to do with authentication. It’s true only for the resource owner. The client needs to authenticate itself every time it asks for an access token. Usually it implies sending the client ID and secret as Basic Authentication plain-text string. SPA applications have no way of “storing“ the secret securely, as it would have to be included in the source code. That’s why the simplified Implicit flow, devised for JavaScript applications as they were understood almost a decade ago, is now officially banned. It omits the client secret, uses only the client ID, and imposes several other limitations. As per storing the client secret on the client side, when using the Authorization Code grant, mobile and native apps have been believed to be secure enough to do it. They are not. The only way traditional Authorization Code grant can be used securely is by rendering your web application server-side. A huge step forward for OAuth for SPA and mobile apps is enriching the Authorization Code with PKCE, which I only link here, as it deserves an article of its own.

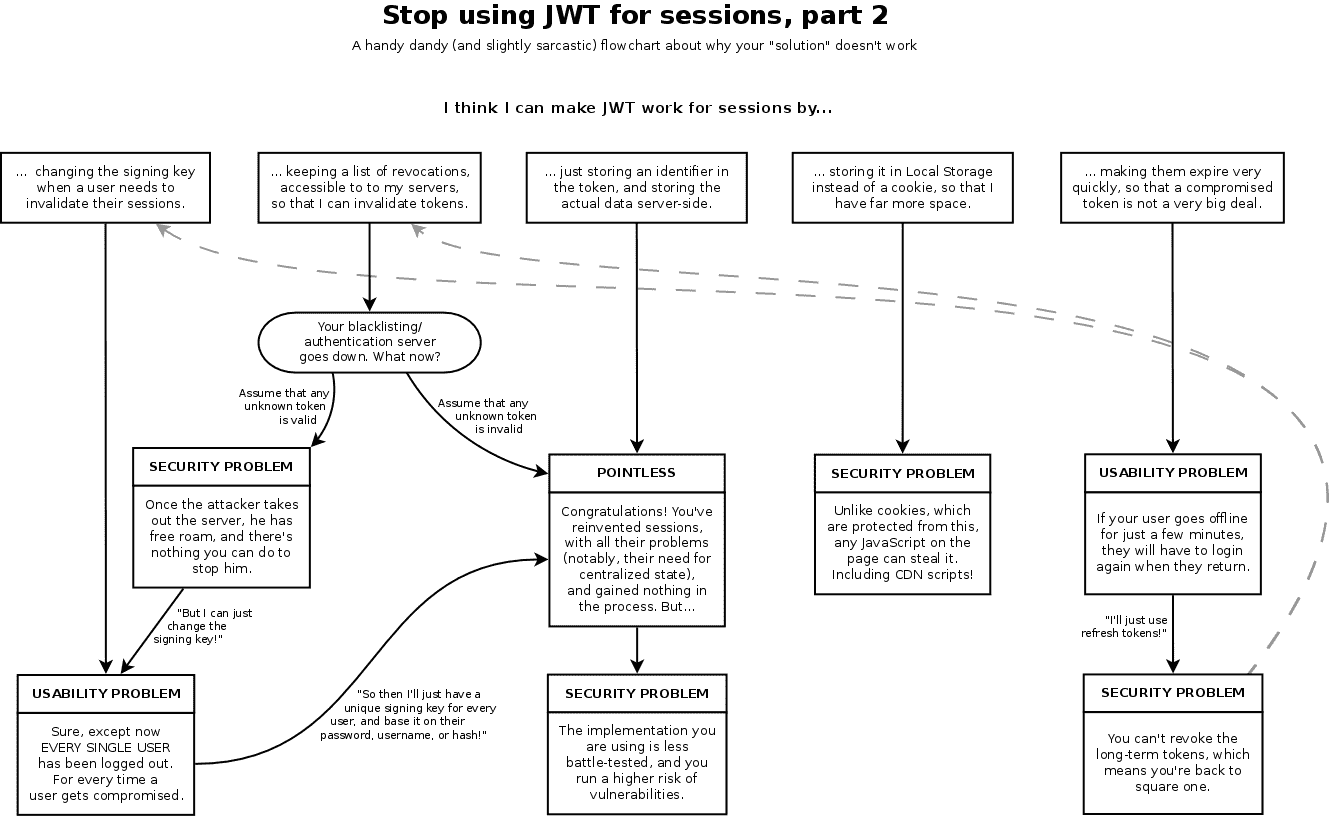

Stateless is a techie euphemism for useless #

Another matter I find very often misunderstood is how OAuth as an authorization framework and OIDC as an authentication framework can be used to secure an app using a completely stateless implementation.

Implementing (fully) stateless authorization and authentication mechanisms requires abandoning the traditional battle-tested server-side sessions with identifiers stored client-side as cookies for (stateless) Json Web Tokens (or some other isomorphic solution).

By stateless JWT I mean an approach where the whole identity and access control context is fetched once when the user logs in (or upon token refresh). Then it’s sent back and forth in form of JWT tokens as cookies (sic!), HTTP request headers or body. I will not dig into the pros and cons of where to store and how to transfer JWTs as this would mean copying and pasting half of the software-literate Internet. You will find the details in the expert articles I link in further sections.

I treat this section as a challenge to prove that an article can be built virtually out of citations only. With minimal intellectual effort from the author. Let’s get started: Unlike sessions - which can be invalidated by the server whenever it feels like it - individual stateless JWT tokens cannot be invalidated. By design, they will be valid until they expire, no matter what happens. This means that you cannot, for example, invalidate the session of an attacker after detecting a compromise. You also cannot invalidate old sessions when a user changes their password.

You are essentially powerless, and cannot ‘kill’ a session without building complex (and stateful!) infrastructure to explicitly detect and reject them, defeating the entire point of using stateless JWT tokens to begin with.

The above and below citations by Sven Slootweg come from this and this article.

Regarding the highlighted session invalidation concerns, the same applies to challenges related to revoking only some of the user privileges without logging them out, so I will not differentiate between these two cases. By stateful JWT you should understand any hybrid that tries to balance what is necessary to store (and potentially invalidate) server-side and the data that can be stored in the browser and transferred in an encoded, encrypted and signed form with every request until it automatically expires. The question is: if something does not require a real-time invalidation - be it a user session or a user privilege - are we still talking about stateless authentication and authorization? Or just about some user data that may be stale so there is no need to fetch them with every request? That’s an entirely different story.

I have an auto-reloading citation clip in my gun:

This can mean that a token contains some outdated information like an old website URL that somebody changed in their profile - but more seriously, it can also mean somebody has a token with a role of admin, even though you’ve just revoked their admin role. Because you can’t invalidate tokens either, there’s no way for you to remove their administrator access, short of shutting down the entire system.

I would appreciate if you suggested an example of an application that needs some security mechanisms but it is not critical to be able to revoke or invalidate them in real time.

I have once read that losing a JWT token is like losing your house keys. Be it true or not, you can always say that you can leave your apartment door open for several minutes if you just go down to the groceries and will be right back. Of course you can, you could also leave your bank account without logging out on a university library computer, there is a good chance the session will expire before someone steals your money. The same applies to the expiry of a JWT session or access token which is not either whitelisted or blacklisted server-side.

When I imagine myself discovering that once I’ve changed my Gmail account password using the desktop app I’m still logged in (even if only for the remaining four minutes) on my mobile app then… Well it’s embarrassing and frightening at the same time, when you think of all the accounts you could potentially reset passwords for by taking over someone’s email account. But yeah, go ahead and just remove the user’s token from local storage.

OK, sit down, it’s citation break:

If you are concerned about somebody intercepting your session cookie, you should just be using TLS instead - any kind of session implementation will be interceptable if you don’t use TLS, including JWT.

Me discovering someone took over the evergreen refresh token to my mail account:

There is no you-meme-it-wrong record I couldn’t break.

Another citation (same source):

Simply put, using cookies is not optional, regardless of whether you use JWT or not.

Yet Another Citation

True statelessness and revocation are mutually exclusive.

Please do look it up in these articles or at least notice how many of them come up.

Now that I’m done with throwing angry links at you, let’s focus on the other side of the problem.

Statelessness is a key to easier scalability #

It’s not true that introducing stateless elements to your authentication and authorization is something wrong. My intention was to play bad cop to emphasize things you have to be careful about. HDD (Hype Driven Development) is a bad practice in general, but as far as security is concerned it’s the shortest path to getting hacked. Every reasonable JWT-based security implementation is a hybrid of stateless, token-based solutions and stateful, server-side-stored solutions. If moving away from traditional, fully stateful implementations is a challenge for your team, you may start with this auth0 article which may make the mind shift easier.

One of the key points from my point of view:

One of the cool things about session IDs is that they are opaque. “Opaque” means no data can be extracted from it by third parties (other than the issuer). The association between session ID and data is entirely done server-side. Are there any other ways of achieving something of the sort without relying on state? Enter cryptography.

The general idea, as mentioned in the OIDC section, is that access tokens should be seen by the client as UUIDs or other meaningless text. It’s the server that should be able to interpret them. That obviously works for traditional session IDs and can be achieved in the JWT-based approach using encryption. Obviously, to achieve revocation you need to store those tokens anyway.

This is where the critics of introducing JWTs in the main authorization flows, as opposed to one-time operations or server-side machine-to-machine communication, hit you hard:

Source: again the Slootweg article

Source: again the Slootweg article

This positions us somewhere between the second and the third “swimlane“ on the above chart, which means keeping a blacklist of revocations to invalidate or storing ID in the token and rest of the data server-side.

It brings you either to:

Your blacklisting/authenticaiton server goes down. What now? Once the attacker takes down the server he has free roam and there is nothing you can do to stop him.

or to:

Congratulations! You’ve reinvented sessions, with all their problems (notably, their need for central state) and gained nothing in the process. But the implementation you are using is less battle tested and you run a higher risk of vulnerabilities.

Yay, time for pasting a JWT body example like in all these other articles:

{

"sub": "some_user_id", //no reasonable case for it to go stale, but dangerous if compromised

"name": "Jason William Toak", //highly unlikely to change, but it's sensitive data

"email": "j.w.toak@somemail.com", //stale email may obviously be a security issue

"scope": [

"admin", //this really sucks if the token is not revocable

"user"

]

}

Obviously, the above token needs to be signed so that you are sure that no one changed its content and it needs to be encrypted as it contains sensitive data. There is a choice of algorithms available. An interesting fact mentioned by Sebastian Peyrott from the auth0 team:

A typical encryption scheme uses an already signed JWT as the payload for encryption. This is known as a nested JWT. It is acceptable to use the same key for encryption and validation.

I guess there is a bottom line that somehow finds a common denominator for both Slootweg and Peyrott manifestos. I do not put these articles in opposition to each other, just as points of view on the same problems from different angles and with different bias. This bottom line, as I see it, is as follows:

- Although JWTs are validated cryptographically, most systems need to use some storage for tokens anyway. By most systems I mean all using refresh tokens, which on its own should, in my opinion, mean virtually each end every token-based application.

- The storage, depending on the application’s requirements, would be either a blacklist or a whitelist of tokens. These can include short-lived access tokens, long-lived refresh tokens, ID tokens or a cartesian product of all the mentioned options.

- The only way for the token storage to prevent leakage is checking every applicable token against the white/black list.

- You can either call it “reinventing sessions“ or “negating some benefits of the token-based approach“, but revocation and statelessness are mutually exclusive and nothing can change it.

- The more you reduce the tokens’ TTL, the less benefit of statelessness you get. I mean that reducing access tokens’ TTL to a reasonable minimum is probably a must-have in most real-life scenarios. Refreshing them is based on refresh tokens stored server-side anyway and a short access tokens’ TTL requires frequent calls to a single point of failure. One still benefits on using a semi-stateless solution, yet the fully stateless one is usually fiction. “The Benefits of Going Stateless“, a slogan which starts Peyrott’s article, is actually just a figure of speech.

- For some systems even a five seconds long access token validity may be a security breach.

- Rolling the signing key is always an option, but it’s like a nuclear suicide attack on your users’ sessions.

- Even if you check every token against some kind of storage, this does not mean you are back to centralized sessions, you still greatly reduce the number of HTTP calls regarding user identity, privilege and other data you choose to fit into a token.

- Let’s emphasize that again: there is a huge difference between accessing a VALID/INVALID key-value storage with every request versus querying a set of storages for distributed user-related data, and aggregating them for every request.

- In a microservice architecture it’s a COLOSSAL, crucial change, which means a difference between a system that barely crawls and one that performs very well.

- In an event-driven microservice architecture, you can handle both user log-outs and privilege revocation or stale data with events invalidating corresponding tokens. Generating a new token does not necessarily mean fetching all data again, it depends on the granularity of information included in the event.

- Does it mean latency, possible race conditions, eventual consistency? Well, yeah, just as pretty much everything does nowadays.

Summary #

Authorization, authentication, statelessness, revocation, tokens, sessions.

Lots of stuff easy to misunderstand, implement the wrong way, oversimplify and wrongly criticise.

OAuth, JWT, OpenID Connect, Authorization Code Grant, Implicit Flow, User and Client Credentials, Third-Party Identity Providers, Delegated Authorization, Federated Identity Management.

That’s again a lot of words and it’s not even a sentence, though a nice SEO booster ;) We’ve gone more or less through all of that, but studying all these terms in detail here was impossible. Should there be at least one thing this article made clear to you and if you feel some misconceptions have been clarified, I’m very happy. If there is at least one comment below this article which will prove me wrong in some or most of views on this broad subject, I will be more than happy to learn something and exchange opinions. As I’ve mentioned in the beginning of the article, security is not something most of us can study, implement and work with every day. Please feel invited to share your knowledge and experience, also including stuff that looks good on paper, but didn’t work for you in production. I will appreciate it a lot.