Impact of data model on MongoDB database size

So I was tuning one of our services in order to speed up some MongoDB queries. Incidentally, my attention was caught by

the size of one of the collections that contains archived objects and therefore is rarely used. Unfortunately I wasn’t

able to reduce the size of the documents stored there, but I started to wonder: is it possible to store the same data

in a more compact way? Mongo stores JSON that allows many different ways of expressing similar data, so there seems

to be room for improvements.

It is worth asking: why make such an effort in the era of Big Data and unlimited resources? There are several reasons.

First of all, the resources are not unlimited and at the end we have physical drives that cost money to buy, replace, maintain, and be supplied with power.

Secondly, less stored data results in less time to access it. Moreover, less data means that more of it will fit into cache, so the next data access will be an order of magnitude faster.

I decided to do some experiments and check how the model design affects the size of database files.

I used a local MongoDB Community Edition 4.4 installation and I initially tested collections containing 1 million and 10 million documents. One of the variants contained up to 100 million, but the results were proportional (nearly linear). Therefore, in the end I decided to stop at 1M collections, because loading the data was simply much faster.

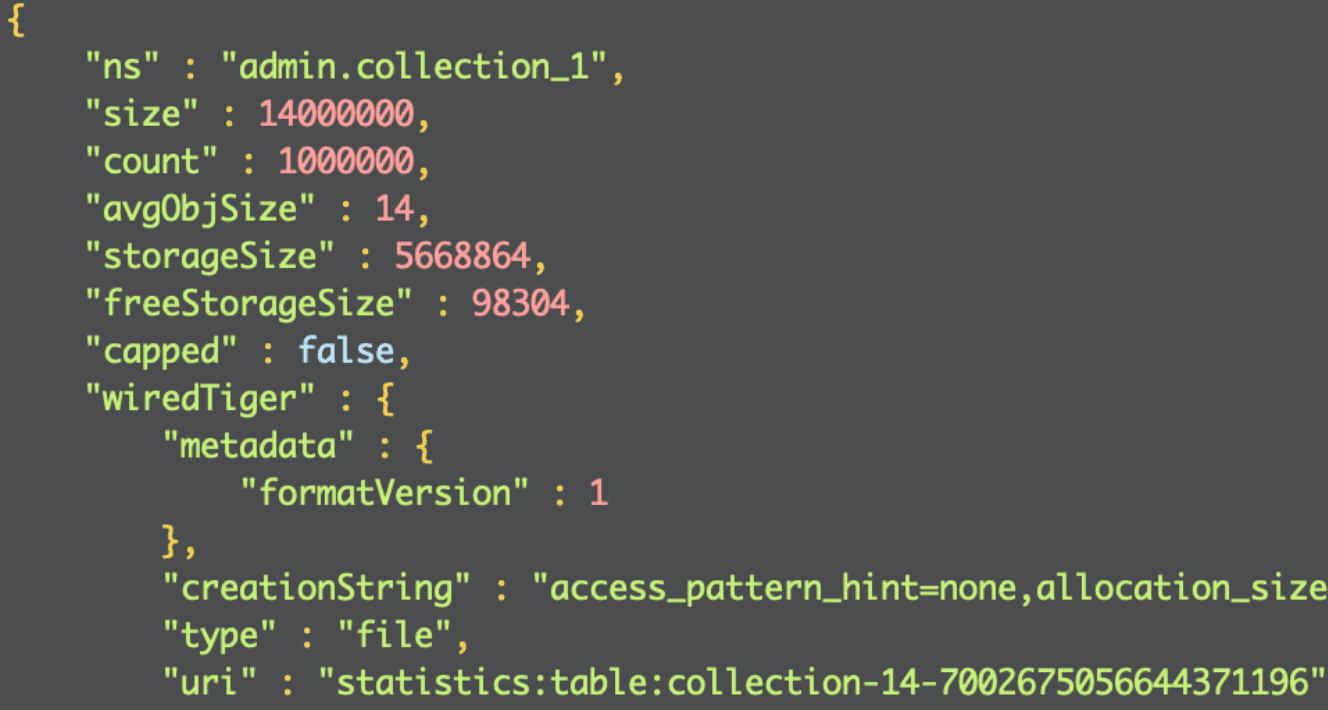

Having access to local database files, I could easily check the size of the files storing individual collections. However, it turned out to be unnecessary, because the same data can be obtained with the command:

db.getCollection('COLLECTION_NAME').stats()

The following fields are expressed in bytes:

size: size of all collection documents, before compression,avgObjSize: average document size, before compression,storageSize: file size on the disk; this is the value after the data is compressed, the same value is returned bylscommand,freeStorageSize: size of unused space allocated for the data; Mongo does not increase the file size byte-by-byte, but allocates a percentage of the current file size and this value indicates how much data will still fit into the file.

To present the results I used (storageSize - freeStorageSize) value that indicates the actual space occupied by the data.

My local MongoDB instance had compression enabled. Not every storage engine has this option enabled by default, so when you start your own analysis it is worth checking how it is in your particular case.

Id field type #

In the beginning I decided to check ID fields. Not the collection primary key, mind you – it is ‘ObjectId’ type by

default and generally shouldn’t be changed. I decided to focus on user

and offers identifiers which, although numerical, are often saved as String in Mongo. I believe it comes partly due to

the contract of our services - identifiers in JSON most often come as Strings and in this form they are later stored

in our databases.

Let’s start with some theory: the number of int32 type in Mongo has a fixed size of 4 bytes. The same number

written as a String of characters has a size dependent on the number of digits; additionally it contains the length of

the text (4 bytes) and a terminator character. For example, the text “0” is 12 bytes long and “1234567890” is 25 bytes

long. So in theory we should get interesting results, but what does it look like in reality?

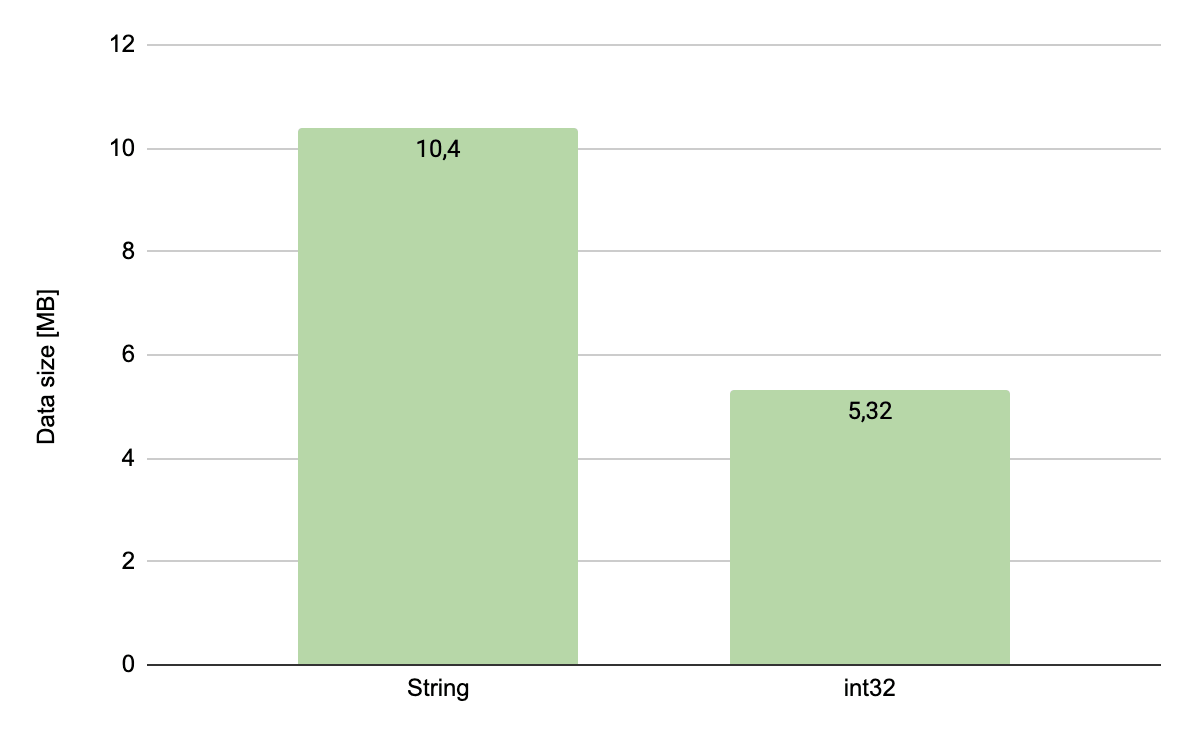

I prepared 2 collections, one million documents each, containing the following documents:

{ "_id" : 1 }

and

{ "_id" : "1" }

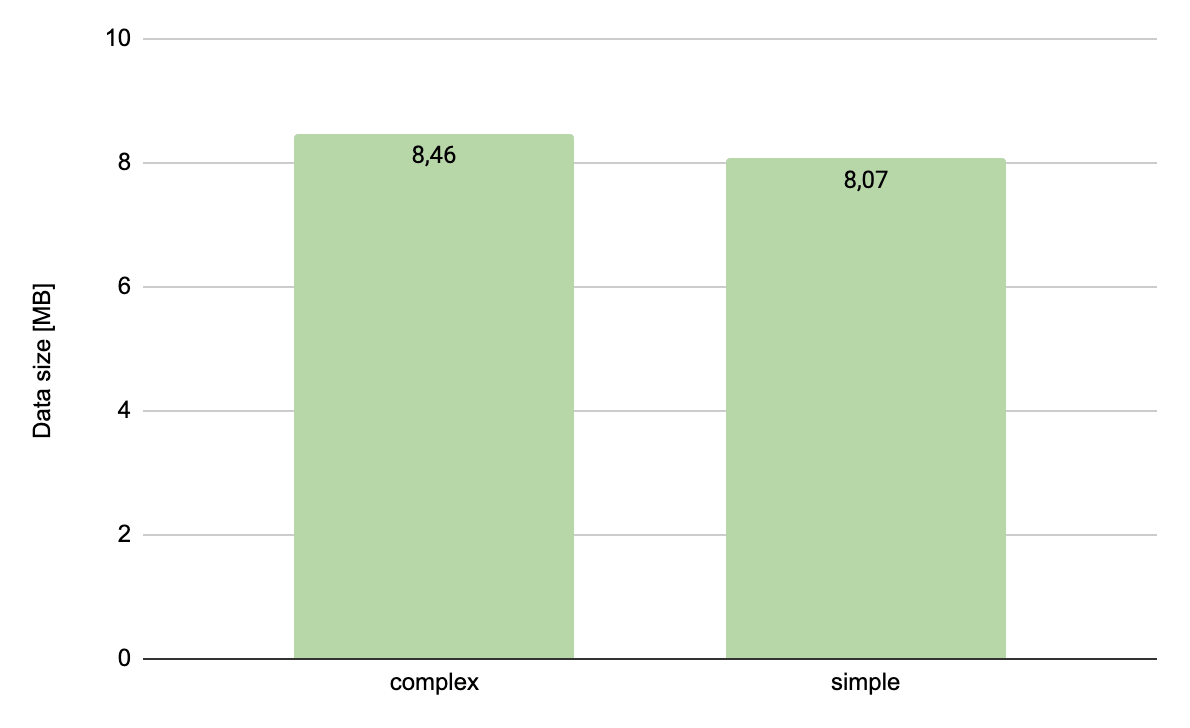

The values of identifiers were consecutive natural numbers. Here is the comparison of results:

As you can see the difference is significant since the size on disk decreased by half. Additionally, it is worth

noting here that my data is synthetic and the identifiers start from 1. The advantage of a numerical identifier over a

String increases the more digits a number has, so benefits should be even better for the real life data.

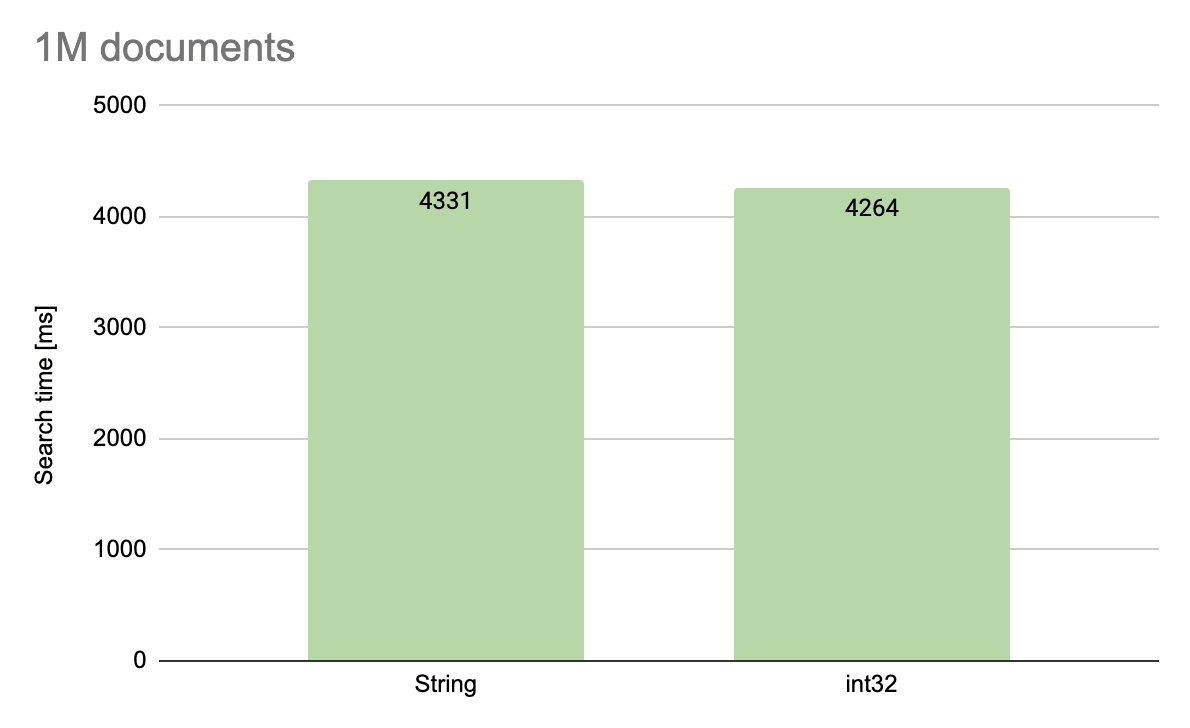

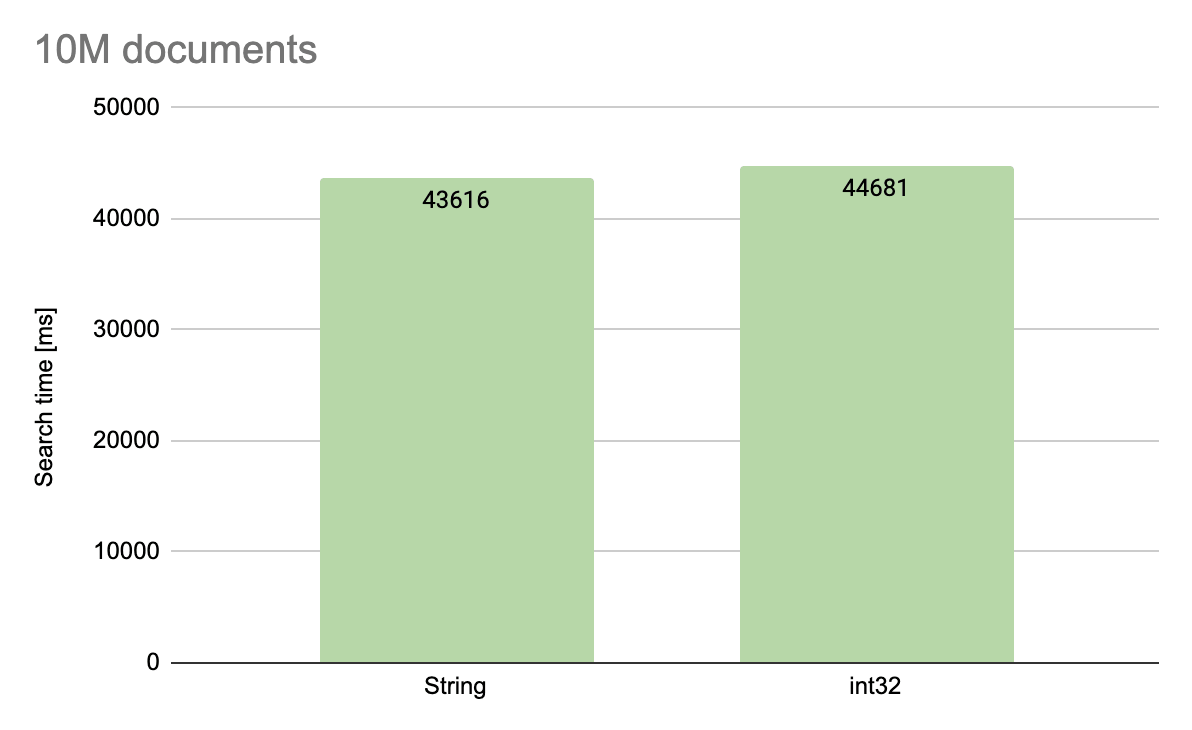

Encouraged by the success I decided to check if field type had any influence on the size of an index created on it. In this case, unfortunately, I got disappointed: the sizes were similar. This is due to the fact that MongoDB uses a hash function when creating indexes, so physically both indexes are composed of numerical values. However, if we are dealing with hashing, maybe at least searching by index in a numerical field is faster?

I made a comparison of searching for a million and 10 million documents by indexed key in a random but the same order for both collections. Again, a missed shot: both tests ended up with a similar result, so the conclusion is this: it is worth using numerical identifiers, because they require less disk space, but we will not get additional benefits associated with indexes on these fields.

Simple and complex structures #

Let’s move on to more complex data. Our models are often built from smaller structures grouping data such as user, order or offer. I decided to compare the size of documents storing such structures and their flat counterparts:

{"_id": 1, "user": {"name": "Jan", "surname": "Nowak"}}

and

{"_id": 1, "userName": "Jan", "userSurname": "Nowak"}

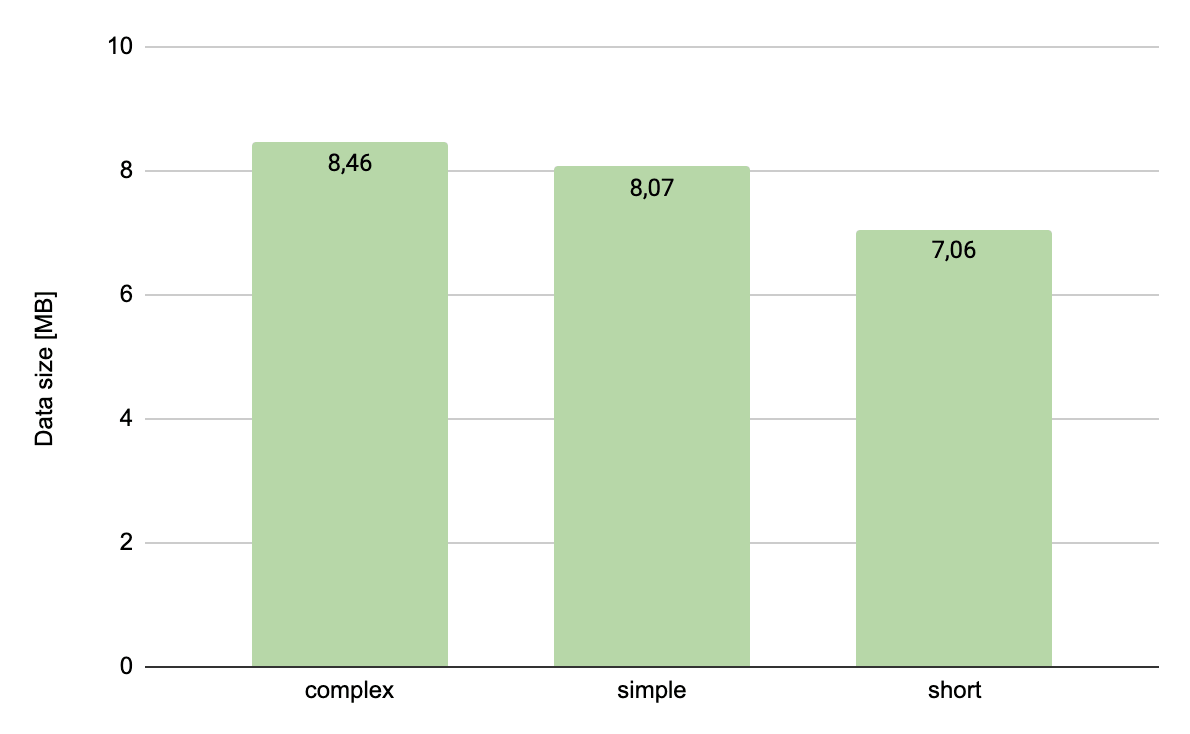

In both cases we store identical data, the documents differ only in the schema. Take a look at the result:

There is a slight reduction by 0.4MB. It may seem not much compared to the effect we achieved for the field containing an ID. However, we have to bear in mind that in this case we were dealing with a more complex document. It contained – in addition to the compared fields – a numerical type identifier that, as we remember from previous experiments, takes up about 5MB of disk space.

Taking this into account in the above results we are talking about a decrease from 3.4MB to 3MB. It actually looks better as percentage - we saved 12% of the space needed to store personal data.

Let’s go back to the discussed documents for a moment:

{"_id": 1, "user": {"name": "Jan", "surname": "Nowak"}}

and

{"_id": 1, "userName": "Jan", "userSurname": "Nowak"}

A watchful eye will notice that I used longer field names in the document after flattening. So instead of user.name

and user.surname I made userName and userSurname. I did it automatically, a bit unconsciously, to make the

resulting JSON more readable. However, if by changing only the schema of the document from compound to flat we managed

to reduce the size of the data, maybe it is worth to go a step further and shorten the field names?

I decided to add a third document for comparison, flattened and with shorter field names:

{"_id": 1, "name": "Jan", "surname": "Nowak"}

The results are shown in the chart below:

The result is even better than just flattening. Apart from the document’s key size, we achieved a decrease from 3.4MB to 2MB. Why does this happen even though we store exactly the same data?

The reason for the decrease is the nature of NoSQL databases that, unlike the relational ones, do not have a schema

defined at the level of the entire collection. If someone is very stubborn, they can store user data, offers, orders and

payments in one collection. It would still be possible to read, index and search that data. This is because the

database, in addition to the data itself, stores its schema with each document. Thus, the total size of a document

consists of its data and its schema. And that explains the whole puzzle. By reducing the size of the schema, we also

reduce the size of each document, i.e. the size of the final file with the collection data. It is worth taking this into

account when designing a collection schema in order not to blow it up too much. Of course, you cannot go to extremes, because

that would lead us to fields named a, b and c, what would make the collection completely illegible for a human.

For very large collections, however, this approach is used, an example of which is the MongoDB operation log that contains fields called:

- h

- op

- ns

- o

- o2

- b

Empty fields #

Since we are at the document’s schema, it is still worth looking at the problem of blank fields. In the case of

JSON the lack of value in a certain field can be written in two ways, either directly - by writing null in its value -

or by not serializing the field at all. I prepared a comparison of documents with the following structure:

{ "id" : 1 }

and

{ "id" : 1, "phone" : null}

The meaning of the data in both documents is identical - the user has no phone number. However, the schema of the second document is different from the first one because it contains two fields.

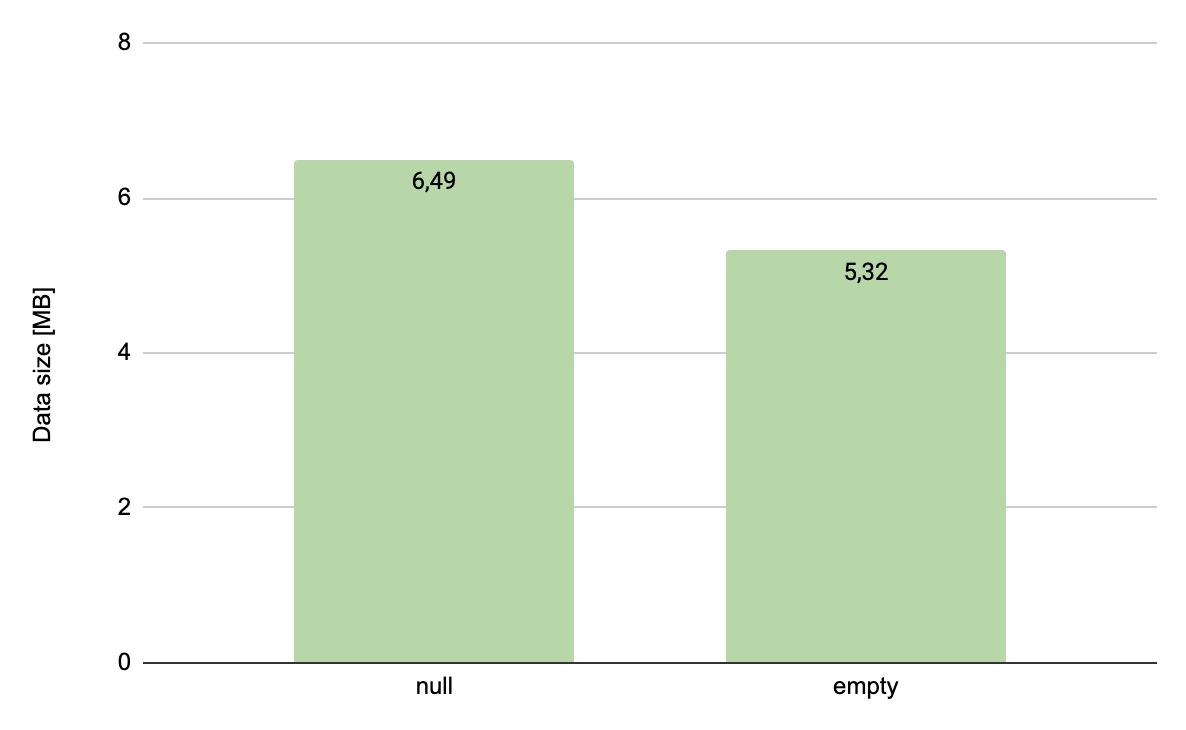

Here are the results:

The results are quite surprising: saving a million null’s is quite expensive as it takes more than 1MB on a disk.

Enumerated types #

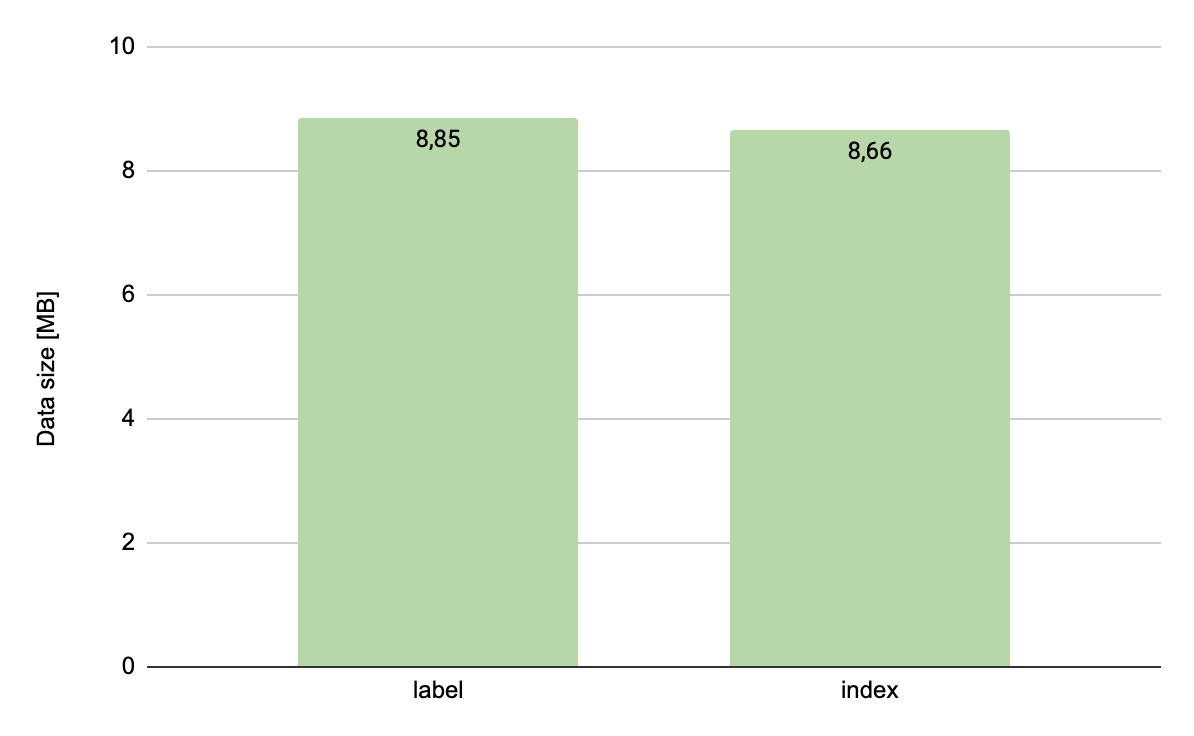

Now, let’s also look at the enumerated types. You can store them in two ways, either by using a label:

{"_id": 1, "source": "ALLEGRO"}

or by ordinal value:

{"_id": 1, "source": 1}

Here an analogy with the first experiment can be found: again we replace a character string with a numerical value. Since we got a great result the first time, maybe we could repeat it here?

Unfortunately, the result is disappointing and the reduction in size is small. However, if we think more deeply, we will come to the conclusion that it could not have been otherwise. The enumerated types are not unique identifiers. We are dealing only with a few possible values, appearing many times in the whole collection, so it’s a great chance for MongoDB data compression to prove its worth. Most likely the values from the first collection have been automatically replaced by the engine to its corresponding ordinal values. Additionally, we don’t have any profit on the schema here, because they are the same in both cases. The situation might be different for collections that do not have data compression enabled.

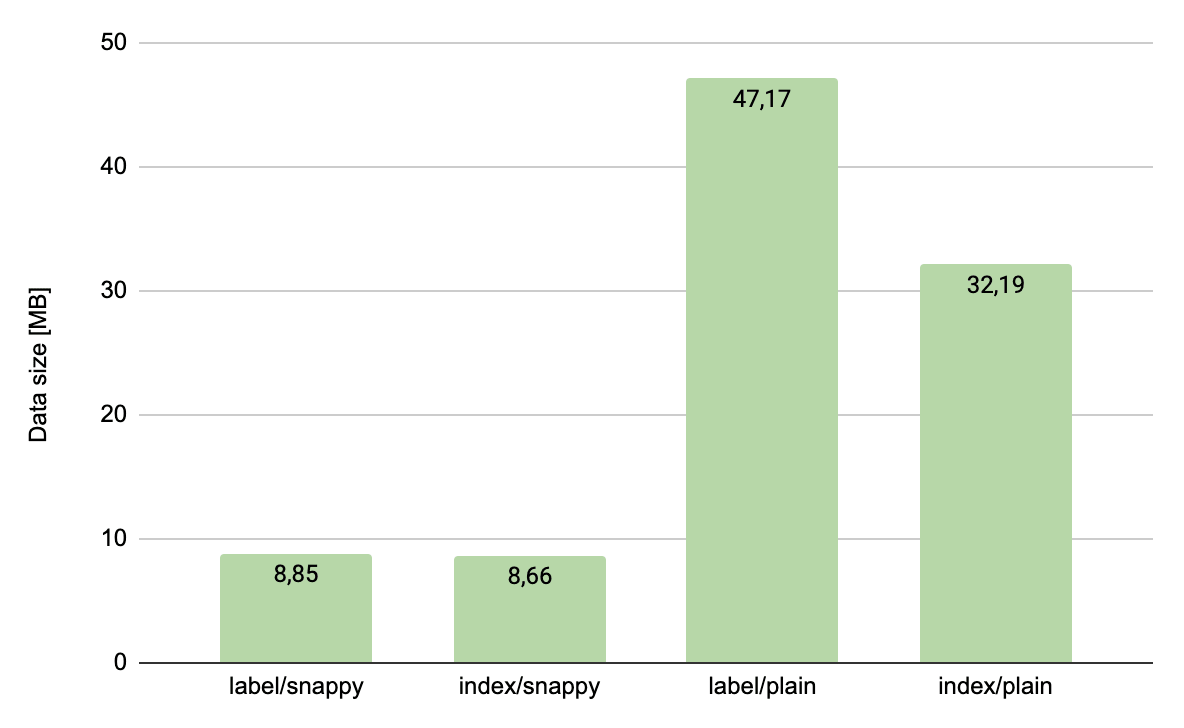

This is a good time to take a closer look at how snappy compression works in MongoDB. I’ve prepared two more collections, with identical data, but with data compression turned off. The results are shown in the chart below, compiled together with the collections with data compression turned on.

It is clear that the use of an ordinal value instead of a label of the enumerated type brings considerable profit for collections with data compression disabled. In case of lack of compression it is definitely worth considering using numerical values.

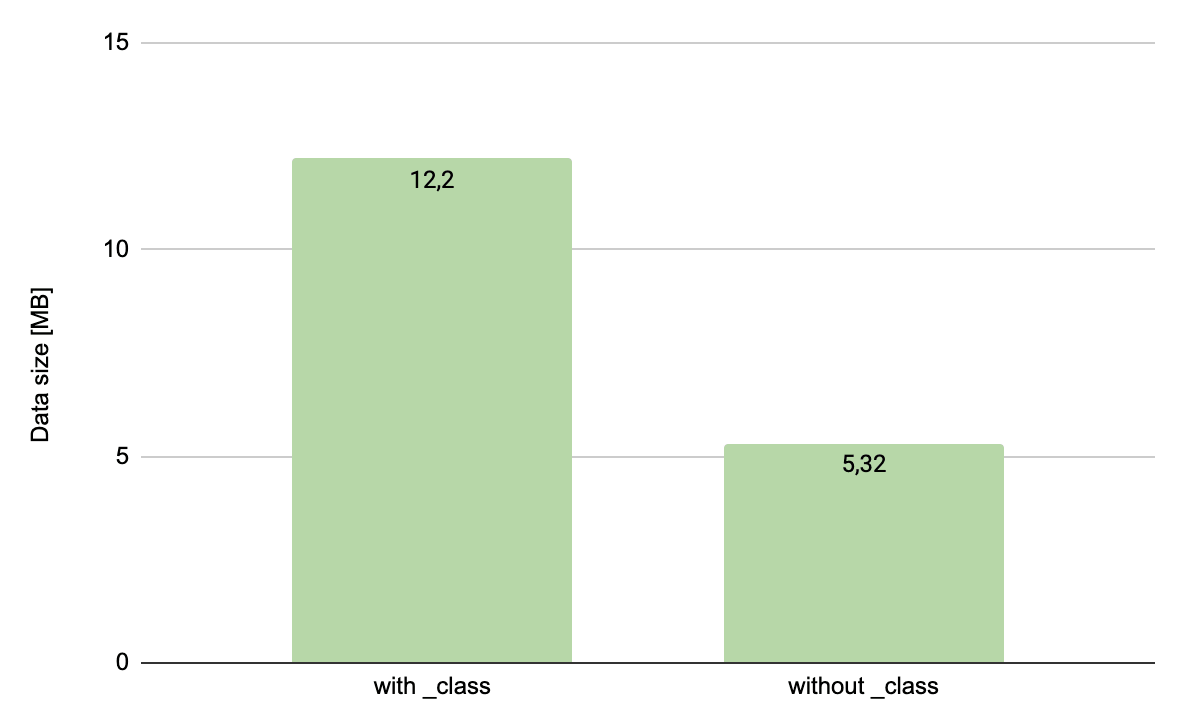

Useless _class field #

If we use spring-data, each of our collections additionally contains a _class field storing the package and the

name of the entity class containing the mapping for documents from this collection. This mechanism is used to support

inheritance of model classes, that is not widely used. In most cases this field stores exactly the same values for each

document what makes it useless. And how much does it cost? Let’s compare the following documents:

{"_id": 1}

and

{"_id": 1, "_class": "pl.allegro.some.project.domain.sample"}

The difference is considerable, over 50%. Bearing in mind that the compression is enabled, I believe that the impact of

the data itself is small and the result is caused by the schema of the collection containing only the key being half as small

as the one with the key (1 field vs 2 fields). After removal of the _class field from a document with more fields,

the difference expressed in percent will be much smaller of course. However, storing useless data does not make sense.

Useless indexes #

When investigating the case with identifiers stored as strings, I checked whether manipulating the data type could reduce the index size. Unfortunately I did not succeed, so I decided to focus on the problem of redundant indexes.

It is usually a good practice to cover each query with an index so that the number of collscan operations is as small as

possible. This often leads to situations where we have too many indexes. We add more queries, create new indexes for

them, and often it turns out that this newly created index takes over the queries of another one.

As a result, we have to maintain many unnecessary indexes, wasting disk space and CPU time.

Fortunately, it is possible to check the number of index uses with the query:

db.COLLECTION_NAME.aggregate([{$indexStats:{}}])

It allows you to find indexes that are not used so you can safely delete them.

And finally, one more thing. Indexes can be removed quickly, but they take much longer to rebuild. This means that the consequences of removal of an index by mistake can be severe. Therefore it is better to make sure that the index to be deleted is definitely not used by any query. The latest MongoDB 4.4 provides a command that helps to avoid errors:

db.COLLECTION_NAME.hideIndex(<index>)

The above-mentioned command hides the index from the query optimizer. It does not take this index into account when building the query execution plan, but the index is still updated when modifying documents. Thanks to that, if it turns out that it was needed, we are able to restore it immediately and it will still be up-to-date.

Conclusion #

Using a few simple techniques, preparing several versions of the schema and using stats() command we are able to design a model which does not overload our infrastructure. I encourage you to experiment with your own databases. Maybe you too can save some disk space and CPU time.