Grouping and organizing Java classes

One of the first challenges a programmer has to face is organizing classes within a project. This problem may look trivial but it’s not. Still, it’s worth spending enough time to do it right. I’ll show you why this aspect of software development is crucial by designing a sample project’s architecture.

Assumptions #

Let’s assume that we have to create a “Project Keeper” application for managing projects at an IT company. Thanks to the application, project managers will be able to create projects and assign teams to them. We know that after some time, the DI (dependency injection) framework currently used by the company’s software will be replaced by another solution. As part of cost reduction, the company plans to stop using a commercial relational database and replace it with some open-source solution. The application has to be primarily available via HTTP through a browser. Sometimes, however, access from an operating system terminal will be needed.

Implementation #

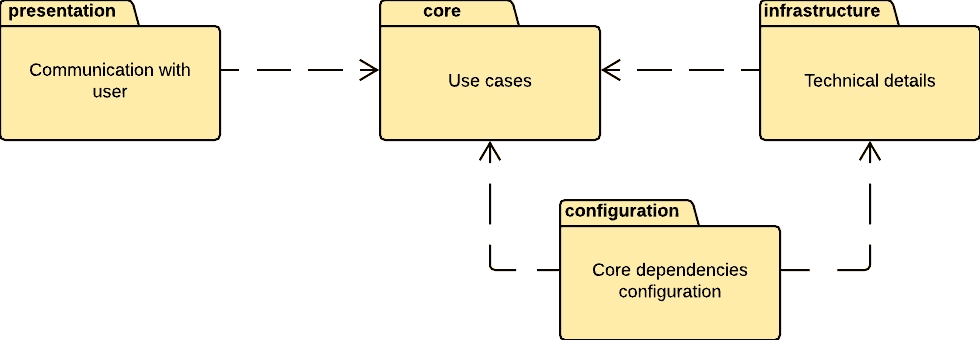

Bearing in mind the above assumptions, we want to implement the application in such a way that it is easy to introduce the changes mentioned in them. Let’s think for a moment what our application really is. The main part of it will be business logic, that is the use cases that we expose to users. Let’s call this part of the application the core. This is where the most important but also the most complex source code will reside. Therefore we should limit the need to change the code to the minimum in the core part. To achieve that, we will make the core completely independent of the other application parts. Users must be able to use available use cases, which is why they should be presented to them in some way. At the moment, the use cases are to be presented via the HTTP API that the frontend application will consume and via the operating system’s terminal. If we isolate the part responsible for presenting use cases, we can freely change the presentation methods in the future without affecting the core. Let’s call this part of the application the presentation. Our application will need to communicate with an external system: a database. The database will soon be replaced by a different one. It would be good not to change any code in the core when replacing the database. We will achieve this by introducing the next part of the application: the infrastructure. The infrastructure will be responsible for communicating with database (or any other external system if they appear in the future), but also for all other technical aspects not related to the business logic. It turns out that this is not an innovative view of the application. The above approach to splitting the application is one of the fundamental assumptions of Domain-Driven Design, Clean and Hexagonal architectures. The assumptions of our application show that it must be prepared for changing the DI framework. This is a rather rare thing you do in real world but in our case we must be prepared for it. Again, let’s follow the rule that the core stays intact when changing the DI framework. Let’s make the core independent of the DI framework by not using any of the framework’s classes or annotations in the core. Such independence will also make it easier for us to test the core in isolation if we decide to implement such tests. By getting rid of the framework from the core, we get rid of the possibility of using automatic DI. We must therefore manually configure all dependencies. Let’s introduce the next part to the application: core configuration, where we will do it.

Now we need to determine one very important detail: the relationships between application parts. To get things working as described above the core must be completely independent of infrastructure, presentation and configuration. This means that no class from outside the core can be used in the core. The relationships between the parts of the application will look like this:

In Java we can represent each of the application part as a package. Let’s divide our project into main packages:

com.itcompany.projectkeeper

├── configuration

├── core

├── infrastructure

└── presentation

Now, that we have came down to the package level of our application, let’s start thinking about making the code easy to read and change.

This is the tricky part of application design because at the moment of writing the code and short after, a developer knows exactly how the code is constructed and how the use cases’ logic flows through it.

But after a while, he often forgets those flows and the code starts to appear messy and hard to maintain.

Good code reviews may help but it is better to create a good source code from the very beginning.

There are many good practices you should consider i.e. Domain-Driven Design, Clean and Hexagonal architectures, various design patterns.

From my experience though, there are two most important rules to follow.

The first one you should already know, as I have already mentioned it couple times: make the core package independent from other packages.

The second one is encapsulation.

Encapsulation means hiding internal details of packages and classes from other packages and classes.

Why those two rules are so important?

The most unpleasant source code to work with is that which has the most number of dependencies between packages and classes.

In highly coupled code even a small change can create stream of changes around the whole codebase.

Not to mention that first you have to spend hours to understand what the code is really doing and how.

Therefore the code needs to be as loose as possible and for that you need to limit the dependencies in it to the minimum.

This is where the independent core and encapsulation rules shines.

Thanks to them we can:

- clearly define the rules of communication between packages

- be sure that the class will not be used incorrectly and/or in the wrong place

…and creating so-called spaghetti code will be seriously hindered :)

Let’s now focus on each package individually.

Core #

The business logic will focus on projects and teams.

At the IT company, various teams deal with various types of projects.

For example, programmers create software, UX designers design user interfaces, analysts analyze data.

Project type is therefore something common to the project and the team.

Let’s map all of this to the application’s structure by adding additional packages to the core:

com.itcompany.projectkeeper ├── configuration ├── core │ ├── common │ ├── project │ └── team ├── infrastructure └── presentation

By doing it that way we make it easy to:

- deduce the purpose of the application

- find classes operating on individual domain objects

- use class visibility restrictions to encapsulate internal packages’ aspects

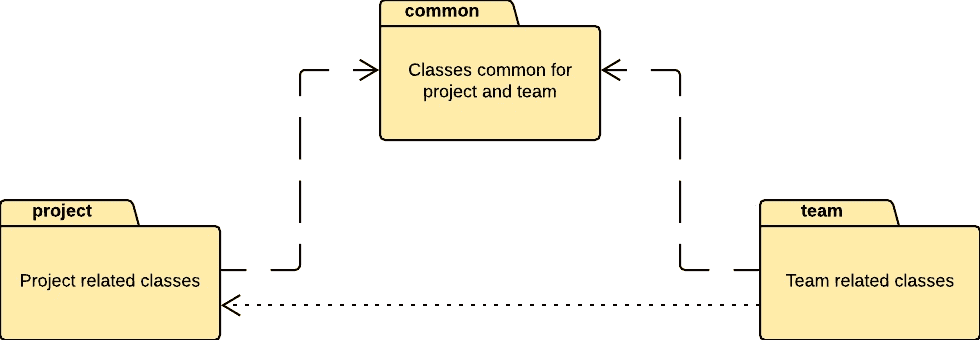

Here we also need to determine the dependencies between the packages.

The common package should not have any dependencies.

In an ideal world, the project and team packages should depend only on the common package.

In practice, this is often not the case.

Let’s assume that each team is evaluated based on the number of completed projects.

In this situation, the team package must also depend on the project package because information about which project has been completed must be passed on to the team package.

Let’s try to make this relationship as loose as possible.

Let’s present the dependencies between the packages in the core package on the diagram below:

Now, let’s think about how to encapsulate the project package.

Generally, the fewer public classes and methods the better.

Let’s first create a publicly available ProjectService, which will be the entry point to the project package.

According to Domain-Driven Design, we extract the Project aggregate.

Ideally, the Project methods would have a package-private visibility, but as I mentioned earlier, the team package will need access to the Project.

To minimize this dependency, let’s make only those Project methods public that do not change Project state.

With this approach, only the project package will have control over the Project object.

The state of the Project needs to be persisted outside the application, for this we will use the ProjectRepository repository.

In order to make the core independent from the infrastructure, the repository must be an abstract entity.

I suggest using an abstract class for this, not an interface, because class methods may have protected visibility.

Thus, they will not be visible outside the project package.

We’ll limit the visibility for the rest of the project’s classes to package-private one.

Let’s do the same with the team package, let’s create the TeamService, Team and TeamRepository classes.

Let’s also add a ProjectType to the common package.

In the common package most classes will have public visibility.

Similarly to the project and team packages, let’s create an entry point for the core package: a ProjectKeeper class.

The only stateless classes that the ProjectKeeper can access are ProjectService and TeamService.

So let’s delegate work from the ProjectKeeper to them.

For the ProjectKeeper to be usable, you will need a number of DTO objects.

The project structure now looks like this:

com.itcompany.projectkeeper ├── configuration ├── core │ ├── common │ │ └── ProjectType.java │ │ └── *.java │ ├── project │ │ ├── Project.java │ │ ├── ProjectRepository.java │ │ ├── ProjectService.java │ │ └── *.java │ ├── team │ │ ├── Team.java │ │ ├── TeamRepository.java │ │ ├── TeamService.java │ │ └── *.java │ ├── ProjectKeeper.java │ └── *Dto.java ├── infrastructure └── presentation

Infrastructure #

In the infrastructure package, let’s specify how to save Project and Team aggregates and let’s specify the configuration of the database connection.

We do this in the persistence and commercialdb packages, respectively.

I recommend naming configuration infrastructure’s packages same as the external systems are named.

This will allow developers to know what are those systems just by looking at the packages.

This is actually analogical to core’s packages naming: the business propose of the application is more or less known just by looking at the packages.

We define the way of saving aggregates by creating a CommercialDbProjectRepository and a CommercialDbTeamRepository, which will implement the core’s repositories.

In case of database replacement, we will only replace these implementations and the core package will remain intact.

Let’s configure the connection to database in the CommercialDbConfiguration class.

The framework’s capabilities can help us encapsulate packages.

Thanks to its automatic DI, we can limit the visibility of all classes to package-private.

Let’s change the structure of the project:

com.itcompany.projectkeeper ├── configuration ├── core │ ├── common │ │ └── ProjectType.java │ │ └── *.java │ ├── project │ │ ├── Project.java │ │ ├── ProjectRepository.java │ │ ├── ProjectService.java │ │ └── *.java │ ├── team │ │ ├── Team.java │ │ ├── TeamRepository.java │ │ ├── TeamService.java │ │ └── *.java │ ├── ProjectKeeper.java │ └── *Dto.java ├── infrastructure │ ├── commercialdb │ │ └── CommercialDbConfiguration.java │ └── persistence │ ├── CommercialDbProjectRepository.java │ └── CommercialDbTeamRepository.java └── presentation

Presentation #

In the http and console packages, we implement access to the core package from the HTTP endpoint and the terminal.

For HTTP purpose, let’s add the ProjectKeeperEndpoint using the framework to help us handle the requests.

Let’s also add the ProjectKeeperConsole where we implement access from the terminal.

Both of these classes will access the core package through the ProjectKeeper.

Here, all the exceptions thrown from the core package will be handled.

Classes’ visibilities can be safely set to package-private.

The structure of the project will change as follows:

com.itcompany.projectkeeper

├── configuration

├── core

│ ├── common

│ │ └── ProjectType.java

│ │ └── *.java

│ ├── project

│ │ ├── Project.java

│ │ ├── ProjectRepository.java

│ │ ├── ProjectService.java

│ │ └── *.java

│ ├── team

│ │ ├── Team.java

│ │ ├── TeamRepository.java

│ │ ├── TeamService.java

│ │ └── *.java

│ ├── ProjectKeeper.java

│ └── *Dto.java

├── infrastructure

│ ├── commercialdb

│ │ └── CommercialDbConfiguration.java

│ └── persistence

│ ├── CommercialDbProjectRepository.java

│ └── CommercialDbTeamRepository.java

└── presentation

├── console

│ ├── ErrorHandler.java

│ └── ProjectKeeperConsole.java

└── http

├── ErrorHandler.java

└── ProjectKeeperEndpoint.java

Configuration #

To supply the core package with repositories’ implementations from the infrastructure package, let’s create a ProjectKeeperConfiguration class.

Its task will be to build and expose the ProjectKeeper from the core package to the presentation package.

Let’s use the framework to make the ProjectKeeper class injectable by DI.

The ProjectKeeperConfiguration class may have package-private visibility.

Ultimately, the project looks like this:

com.itcompany.projectkeeper

├── configuration

│ └── ProjectKeeperConfiguration.java

├── core

│ ├── common

│ │ └── ProjectType.java

│ │ └── *.java

│ ├── project

│ │ ├── Project.java

│ │ ├── ProjectRepository.java

│ │ ├── ProjectService.java

│ │ └── *.java

│ ├── team

│ │ ├── Team.java

│ │ ├── TeamRepository.java

│ │ ├── TeamService.java

│ │ └── *.java

│ ├── ProjectKeeper.java

│ └── *Dto.java

├── infrastructure

│ ├── commercialdb

│ │ └── CommercialDbConfiguration.java

│ └── persistence

│ ├── CommercialDbProjectRepository.java

│ └── CommercialDbTeamRepository.java

└── presentation

├── console

│ ├── ErrorHandler.java

│ └── ProjectKeeperConsole.java

└── http

├── ErrorHandler.java

└── ProjectKeeperEndpoint.java

Summary #

A lot of things have been mentioned above so let’s make a brief summary. What I would like you to remember is to:

- divide your application into core, infrastructure, presentation and configuration parts

- make the core completely independent from other parts

- encapsulate packages and classes

- name packages so that looking at their names will tell what the application is doing and how

- follow Domain-Driven Design rules

I can assure you that doing so, your code will enter a whole new level of quality.

If you’ve never delved deeply into topics related to application architecture, I hope that I encouraged you to do so. The presented approach is obviously not the only right way to group classes. It works well in business applications, but for example, it doesn’t quite fit into all kinds of libraries. It also can be enhanced by using Java 9+ modules. If you know/use alternative ways to organize classes into packages, share them in the comments below.

That’s all, thanks for reading! If you need to know more add a comment.