Eight steps to building Minimum Viable Product with Story Mapping

This is the second part of the article about how, in one of the teams at Allegro Group, we combined the Minimum Viable Product (MVP) and Walking Skeleton concepts with the Story Mapping technique to quickly define the scope of the forthcoming project and eventually built a reliable and valuable product in a limited amount of time.

In the first part I described the concepts of MVP and Walking Skeleton and explained how they fit our product.

The following part of the article describes how we used Story Mapping to define the scope of our project and to create a reliable roadmap of our product development.

Walking Skeleton + MVP + Story Mapping = Success? #

Let’s go back one year in time…

The year has just started and winter rules outside the window, while conference rooms in Warsaw, Wrocław and Poznań are buzzing. Our team, although located in three different cities, does whatever it takes to get the MVP version. Let me remind you our situation:

- We have to integrate our product (shipment management platform) with one of the biggest ERP systems in Poland.

- Our current, legacy platform is not ready to handle the increasing amount of traffic, so we need to develop a brand new solution.

- We roughly estimated development to take about two years , but…

- … because of the business arrangements and the release cycle of our ERP partner we have no more than 6 months to deliver the majority of features offered by our current solution.

It was obvious that we didn’t have enough time to build a fully featured product, so we all agreed that we need to use the Walking Skeleton approach and build the Minimum Viable Product. We decided that to bring the skeleton to life, we would use the Story Mapping technique.

Story Mapping is a method first fully described by famous product owners’ coach Jeff Patton. Its main goal is to transform a flat, one-dimensional backlog into a more sophisticated two-dimensional map structure. Story Mapping helps people to describe the product better, preserve its vision and understand customers’ needs.

From our perspective, Story Mapping was a way to understand what was essential to us and, eventually, what our MVP should include. The next few paragraphs describe how we did it.

1. Bring me everyone! Everyone! #

First of all, we gathered everyone: the Scrum Team, stakeholders (including people from customer service team) and all other people involved in the product development. It was particularly important to us. We intuitively knew that the MVP which is not a result of teamwork and not transparent to everyone can lead to some potentially avoidable misunderstandings later.

2. What is the main goal of our product? #

Then, all together, we defined what our product provided or what it should provide to make our customers and our partner’s customers more satisfied. In short: we identified our product’s major features (Jeff Patton calls them The Big User Stories).

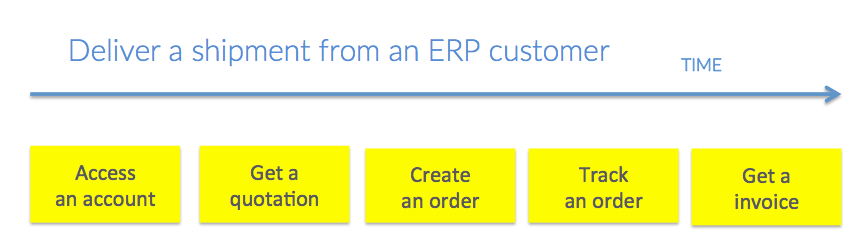

Here is the short list of the major features of our product:

- Creating a parcel order.

- Getting a quotation.

- Tracking orders.

- Accessing user’s account.

- Getting invoices.

- … and few more.

3. What kind of process do we support? #

In the next step, we browsed through the features we had identified before and created a simplified process. The process defined how the majority of users would use our product. We prepared large colorful sticky notes and on each of them we put the stage/feature/big story name. Then, we ordered stickies according to user flow and placed them on the whiteboard. Our process looked like this:

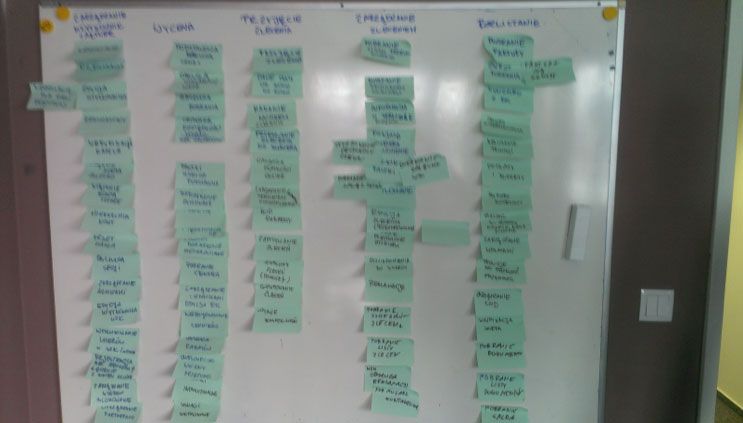

4. Many small bricks #

In the next step, we truly appreciated that we were doing the Story Mapping workshops all together, because we were able to conduct a brainstorming session.

We started by dividing each stage of our process (the big stories) into lists of smaller stories. It was fascinating because there were no bad or useless ideas and everyone was involved into process. The stories were different: some were bigger and some more complex, but together they gave us a hint about how much work was potentially ahead of us.

For instance, we divided “Getting a quotation” into:

- Quotation based on fixed price list.

- Quotation based on dynamic price list.

- Quotation for simple (standard) services.

- Quotation for extra (non-standard) services.

- Support for price ranges adjusted dynamically.

- Support for discount codes.

- …

We learned that smaller stories are better in most cases, because they give us much more flexibility and allow us to adjust our Minimum Viable Product more precisely. We had also learned that the process stages we had described earlier are not fixed and their scope can be changed to visualize our product more completely.

5. Bring order to the galaxy #

Next step was one of the most important ones. We started to prioritize the stories according to their importance. We asked ourselves a few important questions:

- How much value will the story bring?

- How important is the story to finishing the process?

- How much damage will be caused if that story is missing?

- How risky is the story and how much the team can learn from doing it?

If you would like to know what other questions are useful when prioritizing the stories, please refer to Mike Cohn’s book: Agile Estimating and Planning.

Even though we examined one story at the time, we still thought about the entire process. We were wondering which stories where most essential to the basic user flow. We started moving stories on the board, so that the top priority stories were placed at the top of the map, and less important stories were placed at the bottom. The final map looked like this:

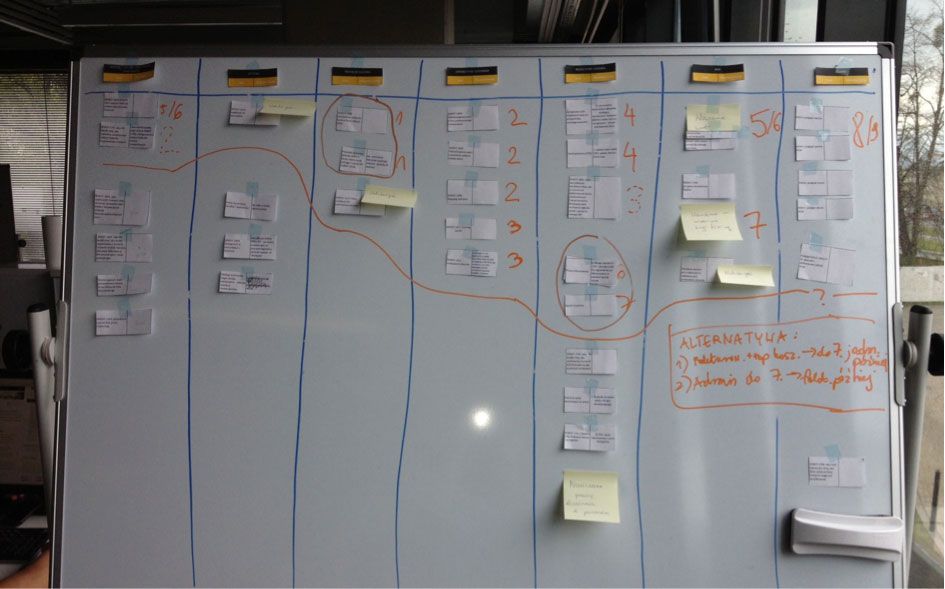

6. Lines on the whiteboard #

In the next step, we decided what should be included in our MVP. It was much easier now, because:

- We saw our product at a glance.

- We had a vision of basic user flow.

- We had clear priorities which defined which stories were most important.

So, our Product Owner drew a line on the whiteboard* and separated the stories which were essential to our MVP and stories which were less important right now. Everything above the MVP line was necessary to meet our users’ needs.

Next, we could draw another line. The second line separated the stories which should be done later to view product as complete, but they were not necessary for the first version of our system. Things above the line were the so-called nice-to-have stories and everything below the line could have been classified as:

- Long-term vision of the product.

- Dreams of the Product Owner.

- Simply - waste.

In all cases, they were not so important right now, because we already had scope that truly mattered - our Minimal Viable Product scope.

*Actually, I can’t precisely recall who grabbed the pen but, as usual, all the credit goes to Product Owner :)

7. Evaluation, evaluation, evaluation #

Although having MVP defined was very important, we needed to have one more piece of information. Back then, we had a fixed deadline which defined how much time we had to finish the project. So, the next non-optional step was the evaluation. We wanted to know how much time (approximately!) we would need to finish all work defined by the scope we all agreed en.

We didn’t have to be that precise — we were working at an agile company and we all knew that the situation might change; but we still needed at least some information. We wanted to know if the scope we defined fit our deadline or it is e.g. 3 times bigger.

As our method of estimation we picked a variation of planning poker and magic estimations. Eventually, we estimated project to take 120 story points. This information was important to us, because with our given and proven velocity we knew that we were able to develop a project with scope estimated to take about 80 points. That is why we had to cut our MVP a bit more and make some stories a bit thinner.

Finally, after some discussions, we agreed on the eventual shape of our MVP and decided to give it a go. The main goal of our workshop has been achieved!

8. Hit the Road, Jack! #

At the end, we decided to create the long-term product roadmap. The first row of our map was the Walking Skeleton - this was the thing that we needed to build first.

Generally, the rule of thumb is: look at the map, and always go right, not down so that the basic user flow is developed first. It is very logical: nobody would care if our system had fancy social login features if it didn’t allow creating a shipment order.

In our case, it wasn’t so easy. We were closely cooperating with our ERP partner (and they used the waterfall approach) so we had to adjust our plan to their schedule. Eventually, our roadmap looked more or less like this (the numbers in the picture represent consecutive sprints):

We had our roadmap defined, so the next step was to… actually start working.

This sounds nice, but… my project is a special case. #

Before I tell you how the MVP and Walking Skeleton approach eventually worked out for us, let me discuss one very important topic.

When you present MVP or Walking Skeleton concepts, you may hear that these are beautiful, theoretical ideas, which can never be delivered in the real world. My project is different, my customer is different and my situation is totally different. Is it? You can hear the same when implementing Scrum or any agile methodology. So where do the successful implementations come from?

Being agile is about the principles, not formulas. Therefore, it is good to try out the “theatre gallery” method. While working on a project, participants sit in the first row, next to the stage. They know all the problems and are used to some type of behavior patterns. They struggle to find a new perspective. A gallery is a mind exercise – taking a look at your project from a different, wider perspective and analyzing the situation while being emotionally neutral.

Working with an ERP system provider who has strict release deadlines and works according to typical waterfall model seemed impossible. But it turned out there are intelligent people on the other side, able to understand the principles and advantages of our work model. Do not try to prove that your model is better – focus on benefits that the two parties can gain. Do not expect that the other party will suddenly convert to your model, as it is impossible.

However, you can reach a compromise. At least it worked for us. After meetings, we adjusted our schedule to suit both parties. Both teams had to adjust, but we managed to find the common model. We focused on creating an API for a customer. At the beginning we based it on mocks, later on we added new layers of logic. The first version of platform did not provide any business value… but it allowed the other party to start their work. It was a great value for both: our partner and us.

And The Happy Ending #

Two simple things:

- We released the product in June, on time.

- Our system offered the majority of features that we wanted.

Therefore, I dare to say that MVP and Walking Skeleton are working, indeed. Of course, there were some problems on the way to deliver it, but it was one of our smoothest releases that we ever experienced. Actually, it was not a release so to speak. We had been releasing the application piece by piece after each sprint, keeping in mind the goals set a few months earlier.

I do not know how we would do it without MVP. Perhaps our product would offer only half of options, perhaps we would be too stressed to work, or perhaps our project would be incomplete? Would any customer use it? I doubt it!

Post Scriptum #

At the end I would like to share with you what we have learned and what we have discovered during the entire development process.

- Teamwork does work, indeed! Our MVP was not created alone by the Product Owner, or alone by the Team. It was visible to everyone interested in the project during the whole time of development. Any negligence here would cause problems, because believe me: MVP means something different to everybody.

- MVP is not created once. It is a constant process that is tweaked all the time. Stories can be moved. Today’s must-to-have option does not have to be such tomorrow. It is crucial to visualize the story mapping to make the progress noticeable to all.

- Neglecting planning is bad. Watching the relation between stories and work progress is good. We had some problems caused by imperfectly monitored stories and even had to stop the work for a while and prepare some stories instead. Beware of that!

- MVP exists on various layers. It may operate:

- on core options (perhaps we do not need the whole set?),

- in single stories (maybe this one is unnecessary?),

- within a story (does our search engine have to make the search by 123 fields?),

- or a technical level (do we really need Hadoop to generate a PDF file?).

-

Focusing on the impact of stories on the product value can help. Pareto Principle states: 20% of effort gives 80% of profit. Is 80% enough? Specific version of the product may process the largest number of cases hence it may be sufficient for the MVP.

-

Automatic tests of implemented changes are crucial. We created automatic tests for each new option added to API. Otherwise, it would be difficult for us to detect regression errors. Without testing, we would have been afraid of any changes, whereas change is one of the pillars of MVP and Walking Skeleton.

-

Often, minimum is not the goal in and of itself. Our objective was to maximize the value, doing minimal scope can sometimes lead to even larger costs.

For example: to minimize the scope we wanted to use CSV files in an admin panel instead of a web interface. We thought it would be easier. It turned out that file processing caused a lot of problems, stress and took 3 weeks to be implemented. Later, we changed that mechanism into a web interface, which took us about a week, i.e. 3 times quicker.

- Things marked as to be done later can cause a lot of trouble. MVP often generates many elements that are to be done later – this may cause some tension if the elements’ priorities are not highlighted properly. It may evoke a feeling among the team and the stakeholders that if something is not done now, it will never be. If such “put-on-hold” stories are located on the roadmap or story mapping, there is an option to go back to them and there is no impression of leaving something behind.

At the end, one final takeaway message: Be brave when creating good products! Be bold and patient!